I am a clown … and I collect moments.

– Heinrich Böll, The Clown (1963)

The first thing I linger over, when I upturn the box onto my bedsheet, is an overexposed photograph of two skinny boys. It depicts me, aged 19, with a collegial arm slung over the shoulders of Ed, an old friend from school. The pair of us are crouched on a boulder on a beach in western Thailand, in the ungainly repose of people who have just hurried into position after setting a camera timer. The image is shot at an angle from below, and the purplish sky overhead prefigures a gathering storm. The rapturous look on my face suggests that I was either unbothered or that I hadn’t noticed. Whatever the case, I was having a good day.

The photo is one of a thousand odds and ends inside a box – specifically, a Reebok shoebox – that long ago became a reliquary for the stash of mementoes I brought home from my first independent trip abroad. It was the sort of journey that was a rite of passage for kids of a certain milieu at the turn of the 20th century, when Gap Year culture was the rage. I’m not sure what propelled me and the two friends I travelled with, beyond some vague cultural determinism; this was just what a lot of British teens did in the hiatus between school and university. Other than the starting point, Cairns, and the return flight from Bangkok, I had little idea of where we were going, or what we could expect to find when we got there.

When I arrived home – 30 pounds lighter, with a penchant for wearing baggy trousers emblazoned with a Chinese dragon, and no doubt insufferable – I transferred the trove of knick-knacks I’d accumulated in my rucksack into a plastic carrier bag from a Bangkok 7-Eleven. Then I crammed it into this shoebox and shoved it in the attic. It’s taken me 20 years to revisit the contents.

It’s anodyne stuff, mostly. There are a few banknotes and coins; street maps of obscure Vietnamese and Cambodian towns; a dozen flyers for backpackers’ bars. Emptied onto a bed, it looks like anyone else’s trash. But to me it memorialises a graduation. By the time I stashed away this box, I think I already knew that I had found an obsession, and a counteragent, potentially, for the fidgety discontent I’d carried through school.

Home, increasingly, had begun to feel like a malaise; away seemed like an instant antidote. It was the escape hatch I’d been searching for.

Sitting at a desk in London 20 years on, those rudderless months in Australia and Southeast Asia belong to an expired world.

I guess it was inevitable, as the pandemic dragged on, that many of us would be plunged into nostalgia for the journeys we took in the past. For while it may be glib to bemoan a lack of adventure in a period of global bereavement and anxiety, the drastic contraction of international movement is likely to be one of COVID-19’s most momentous cultural and economic ramifications. The old way it was practised, at vast scale, and across increasingly porous borders, has begun to look like it might be a terminal casualty. At the time of writing, there are only memories, and the work of reorienting ourselves to a more inert and less hospitable world.

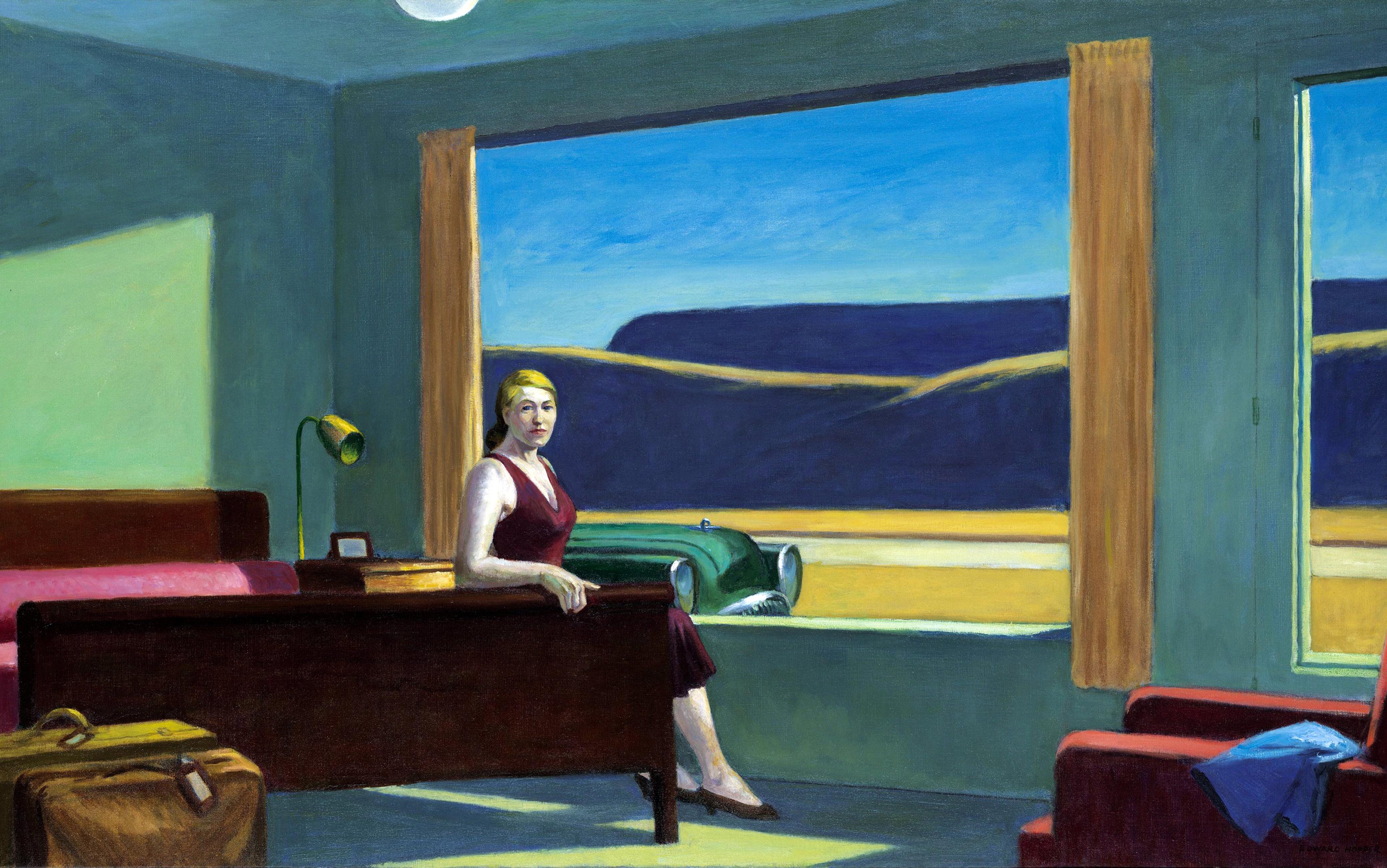

The author in Chilean Patagonia in 2004

I began travelling independently with that trip in 2000, and in the period since I’ve travelled a lot, certainly more than is usual. In hindsight, the best word to describe my compulsion to move isn’t wanderlust but dromomania, because the second word better hints at its obsessive dimensions. It wouldn’t be unfair to think of it as an addiction. A consuming fixation, unthinkable for the vast span of human history, that even today, after months of immobility, I struggle to imagine living without.

Recalling those travels now, it is tempting to view them as having straddled travel’s golden age. In the first 20 years of the millennium, international tourism arrivals more than doubled, from 700 million in 2000 to almost 1.5 billion in 2019. Over that period, travel, for those of us lucky enough to enjoy it, has become synonymous with wellbeing, a vital adjunct of a fulfilling life.

As I determined to write an elegy to this era, however, I was surprised to find myself feeling not just nostalgia but also ambivalence – at once reeling from the cessation of global travel and quietly resigned to the idea that the breakneck experientialism of the pre-COVID world had to be derailed. Why, for me and others, did the desire to experience other places – to feel the joy animating my face in that old photo – evolve into such a burning need? Was there more at play than simply the decadent joy-seeking of a generation who could? Or was it merely a selfish moment in time, one that we now see, in the stark light of a pandemic’s recalibration of our priorities, for the indulgence it always was?

It seems hard to credit, in a society so utterly reconfigured by the digital revolution that was to come, but, for curious kids growing up in the late 1980s and early ’90s, the world still seemed a depthless prospect. Borders were impermeable; the nations they concealed were incomprehensibly varied and vast. It was a world that could only be glimpsed and never surveyed, in which encyclopaedias and atlases hinted at a planet still rife with mystery.

In elementary school, my favourite books were the Adventure series by Willard Price. Published between 1949 and 1980, the 14 slim novels followed the exploits of two brothers, Hal and Roger Hunt, as they travelled the globe collecting rare animals for their father’s Long Island zoo.

Hal, the elder, was the archetypal travelling hero: 17 years old, adept, absurdly brave, ‘as tall and strong as his father’. But I identified more with the younger brother, Roger, who was eager, but green and accident-prone. The stories were surreal in their eventfulness, each chapter opening on another shoot-out or dangerous animal encounter, as the boys careened from one escapade to the next. In Amazon Adventure (1949), the first book in the series, shy and rare jungle creatures – tapirs, anacondas, jaguars – materialise at their feet each time they step ashore. Together, the boys wrestle this temperamental fauna into submission and stuff it aboard a boat they anoint The Ark, upon which they drift down South America’s great river, pursued all the while by the bullets and arrows of psychopathic rivals and head-hunting ‘Indians’.

Reading it back now, it’s tempting to laugh at the narrative’s unlikelihood. We can only wonder at the rationale of the boys’ father, John Hunt, a man of presumably lunatic irresponsibility and questionable ethics, as he dispatches two teenage sons to pilfer endangered species from the four corners of the world.

However, for all their far-fetched plotlines, it occurs to me in hindsight that the books encapsulated much about the life that I, a fatherless kid, easily bored, would grow to covet. The cinematic, event-filled life. The mythic, shadow father. Hal, the surrogate, surmounting every challenge. The boy, feigning courage. It was a pulp fiction allegory for my state of mind. On page 84 of Amazon Adventure: ‘The truth is the kid was scared to death.’

For the time being, my own adventures, and indeed the mainstreaming of adventurous travel, were far in the future. During childhood, I went overseas a handful of times. But we never left Europe, and whatever happiness I found in those trips was transitory, overshadowed as they often were by my mum’s melancholy. It was on such occasions, when convention ordained that life should be at its most pleasurable, that she most felt her solitude. More often, we camped in Devon, or stayed in Welsh caravan parks. And I cajoled my mum into letting me bring friends along, so that we could spend the week sneaking off to smoke cigarettes and weed, and persuading sympathetic hippies to buy us flagons of potent West Country cider.

The truth was that foreign travel as it would grow to be enjoyed was yet to make its full debut. My parents’ generation had Interrailed around Europe. Since the early 1960s, when the first charter flights unlocked the Mediterranean’s mass tourism market, a growing cohort of British holidaymakers had started to venture south for an annual summer vacation. The bourgeoisie had discovered the joys of Alpine skiing. But as far as most Brits were concerned, the far-off places beyond western Europe could stay that way. The geopolitical volatility of the late Cold War, which presented the countries of Africa, Asia and Latin America as theatres of conflict, famine and totalitarianism, didn’t suit the brochures.

Bouncing from bus to border post, I felt restored because I also felt autonomous

Nevertheless, the seeds of my own itinerancy were germinating. It’s interesting to note that, in the argot of the time, a compulsion to travel was often described in chronic terms. A person who loved to go overseas was said to have contracted ‘the travel bug’. A person stuck at home, dreaming of foreign climes, had ‘itchy feet’. What would, within two short decades, grow into a universal pursuit was once analogous to a fungal infection. In my case, the allusion would be fitting, because my compulsion to travel was forged in pathology, even if, in the euphoria of my earliest journeys, I was enjoying myself too much to notice.

Long before it appeared in passport stamps, my itch manifested in a maudlin temper, and a deep-seated dissatisfaction with life at home. In my teenage years, I often found myself gripped by a crushing cynicism that seemed all the more unshakeable as the 21st century arrived with its oil wars, dumb politics and global warming. I had a beatnik disdain for the status quo and often felt stifled by its orthodoxies. Why aim for Oxbridge, start a pension, consider a long-term career path? In some inchoate way, I was convinced I would never harvest the spoils.

Initially, these nihilistic tendencies manifested in typical adolescent misbehaviour, in petty crime, and bongs, and street-corner booze. However, arguably the most peculiar symptom, and perhaps its most consequential, was what I can only describe as an allergy to the familiar, a reluctance to retrace intellectual or physical ground I’d covered before. Anything that was reminiscent of chapters I had already closed – driving past my old school, for instance, or bumping into an old acquaintance I’d once called a friend – made me feel stuck and panicky. After university, as I fell sideways into temporary office jobs of limited utility, sliding my knees under a desk felt like an act of submission. For a spell, walking down to the shops from my mum’s house became a source of despair.

One unfortunate offshoot of this unease was that I often felt ill. All manner of psychosomatic symptoms – that is, the physical presentation of psychological pain – afflicted me throughout my 20s. I’d already become prone to exaggerating the severity of bugs and viruses, wallowing in hypochondriac self-pity with the onset of whatever small malady. But now even minor health complaints would transmute into blue-light medical emergencies: each headache, a brain tumour; each off-colour piss, a harbinger of diabetes; each aching limb, the leading edge of some autoimmune degeneration. Still other ailments were entirely imagined.

The link between emotional anxiety and physical wellbeing was often embarrassingly explicit. I was once working in an office where a colleague related a weekend horror story about her boyfriend having to rush to Accident and Emergency with an ‘impacted testicle’. Two days later, I limped pathetically into the doctor’s office, pleading for someone to investigate an imaginary pang in my own bollock, thinking all the while that I was losing my mind.

It sounds absurdly self-aggrandising to speculate that a few months in Southeast Asia might have presented itself as a cure for this emotional maelstrom. All I can tell you is that, on the move, miraculously, the aches and anxieties would disappear.

Bouncing from bus to border post, I felt restored because I also felt autonomous. The enemy was futility, and my vulnerability was tied to it epidemiologically, like vector and disease. Only by going away, and in so doing defying society’s stifling expectations, could I evade the predestiny clawing at my back. Immobility was a capitulation, a figurative death. So I sought to be untethered.

At home, now, as I pick through the relics of that first, naive journey at the turn of the millennium, each item triggers floods of reminiscence. There’s a cut-out scrawl of a dolphin, drawn by my six-year-old sister, which she handed to me bawling as I shouldered my backpack to leave. A piece of plastic brake handle, which snapped off a hired moped when I lost control of it in a Malaysian alleyway. A page on ‘post-holiday blues’, rudely torn from a discarded Lonely Planet guidebook, which I read in a Khao San Road flophouse on the day we flew home: ‘Life on the road is challenging, exciting and fulfilling while life back home can appear bleak, boring and dreadfully lacking in meaning…’

In many ways, I had stumbled into the arena of international travel at a pivotal moment, just as the New Age backpacker culture that had lured hippies east on a cloud of mysticism and hashish smoke was being fully co-opted by the mainstream.

A month before I boarded the plane to Cairns, Fox Studios had released The Beach (2000) into cinemas. Based on the bestselling 1996 novel by Alex Garland, and directed by Danny Boyle, the film follows Richard (played by Leonardo DiCaprio) on a backpacking journey to Thailand. After drinking some snake blood, he finds his way to a secret island, where an idyllic community lives beside a pristine island lagoon. There he finds joy and love to the ambient strains of Moby’s ‘Porcelain’ (2000), then fucks it all up, and goes insane.

I’d watched the film in a bar in Bali. In those days, backpacker bars throughout Southeast Asia would often show flickering, pirated copies of the latest cinema releases. But I didn’t pay much heed to its allegorical warnings about the dangers of surrendering to serendipity, or its blunt moral that paradise could only ever be ephemeral. I was 19 years old, and preoccupied with finding my own.

‘Mine is the generation that travels the globe and searches for something we haven’t tried before,’ says Richard. ‘So never refuse an invitation, never resist the unfamiliar, never fail to be polite and never outstay the welcome. Just keep your mind open and suck in the experience.’

New experiences have a mnemonic quality – they create a more lasting imprint in the brain

At the end of my own first brush with this zeitgeist, I came home armed with what amounted to a Proustian epiphany: I had come to realise, with a certainty that brooked no contradiction, that fresh experiences emblazoned themselves in the mind at a higher definition, palpably lengthening time. If memories of home-life often seemed diffuse, its events overlapping and abbreviated by familiarity, the ones I carried back from Bangkok were pin-sharp.

Would it make sense if I told you that I can conjure every hump and hollow of that Thailand beach? I can tell you the sand was the colour of bleached coral, that it was fringed with a tangle of low-slung mangroves. I remember that we had just descended from that boulder when it began to rain, and that we hopscotched around washed-up flotsam, drenched to the skin. I can recount how the frothing ebb tide had left dozens of jellyfish stranded every few yards, some of which we attempted to flick back into the surf with a stick, an act which I now realise probably looked thuggish to any bystanders, though I promise it was charitably intended. Later that day, we sat on the beach and watched lightning fork across the sky, except on the horizon, where the dusk broke through in a fan of sunbeams, making silhouettes of the container ships far out to sea.

Possible explanations for the pellucid nature of such recollections are not confined to the philosophical. In recent years, neuroscientists have discerned a clear correlation between novelty and memory, and between memory and fulfilment. Their findings suggest that new experiences have a mnemonic quality – they create a more lasting imprint in the brain. It didn’t seem an unreasonable leap of logic to assume that this might come to be seen as retrospective proof of a person’s rich and happy life.

I recently happened across a multinational study, undertaken in 2016, which investigated the link between novel experiences and the potency of memory. The authors set up an experiment in which mice were introduced to a controlled space and trained to find a morsel of food concealed in mounds of sand. Under normal conditions, researchers found that the mice were able to remember where the food was hidden for around one hour. However, if the environment was altered – in this case, the mice were placed in a box with a new floor material – they could still find the food up to 24 hours later. The introduction of new conditions appeared to magnify the creatures’ power of recall.

Employing a technique known as optogenetics, the study attributed this phenomenon to activity within the locus coeruleus, a region of the mammalian brain that releases dopamine into the hippocampus. Novel experiences, the results seemed to indicate, trigger happy chemicals, which in turn help to produce more indelible engrams, the biochemical traces of memory.

It was with an intuitive version of this self-knowledge that I forged out into the world: a mouse forever in search of a new floor. I spent the years after university shaping my ambitions around overseas adventures, and the months in between desperately saving for the next. Travel writing seemed an obvious alibi, a means of camouflaging my experiential hunger with a veil of purpose. But, in reality, I was engaged in a personal mission to see everything, and I was in a hurry.

My travelling assumed a frantic cadence, as if movement between map pins was a competitive sport. I would travel to the limits of my courage and energy, crisscrossing remote hinterlands, clambering from one clapped-out bus to another, often on no sleep. If I had any particular travelling sensibility it approximated Robert Louis Stevenson’s epigram: ‘I travel not to go anywhere, but to go. I travel for travel’s sake. The great affair is to move.’ It was never my intent to check off a list of sights and animals; this wasn’t some Instagrammer-style process of acquisition and display, at least not explicitly so. More, it was born of a will to reset the view, like an impatient child hitting the lever on a 1980s View-Master, desperate to change the slides.

Ironically, this often placed me in harm’s way. In the Brazilian Amazon, for instance, I was almost killed by a four-year-old child. A hunter had left a loaded shotgun in a dugout canoe, its muzzle resting on the bow, only for his daughter to mistake it for a plaything and pull the trigger. I can still remember the sensation of the buckshot wafting past my abdomen, and wondering out loud, minutes later, how far it might have been to the nearest hospital. (‘Eight hours by outboard motor,’ our teenage guide replied gravely.)

In 2010, I contracted typhoid, dengue fever and bilharzia, in the space of six months. The last of these, a parasitic disease endemic to the Great Lakes region of central Africa, didn’t make itself known until four years later, when streaks of blood in my urine betrayed the Malawian stealth invaders that had been loitering and multiplying in my bladder all that time.

But the perils inherent in my reckless movement always receded after the fact. Often, the close shaves themselves became rose-tinted in the retelling, as if every misadventure was further evidence of my enviable, halcyon life. The perils burnished the story I was writing. It was all part and parcel of the experientialist’s covenant. Again, from Richard in The Beach: ‘If it hurts, you know what? It’s probably worth it.’

As travel democratised, a consensus grew that a storied life must necessarily be a well-travelled one

My symptoms may have been specific and acute, but my choice of remedy for existential anguish was by no means mine alone. In hindsight, I realise I was merely a fanatical disciple of a widespread impulse. For me and many other cynical agnostics, novelty had become the stuff of life. As organised religion waned and we turned away from metaphysical modes of being, experience presented itself as a surrogate for enchantment.

The Western democracies were set on their trajectory: more consumption, more capitalism, more privatisation, which for most people seemed to promise a half-life on a treadmill of work, anxiety and inflexible social norms. But the outside world offered a way out. Only by fleeing the geographical constraints of that staid order was it possible to apprehend its shortcomings – to discover the ways that our own status quo, in its hubristic embrace of what we deemed progress, might have been haemorrhaging precious truths. The Western traveller’s existential epiphany – that pastoralists in the foothills of some impoverished Asian hinterland seemed more at peace with the world than whole avenues of London millionaires – may have been hackneyed and condescending. But to a 20-something in the early 2000s it felt profound. And so we came to see a full passport as a testament, not just to a life well lived, but to some essential insights into the human condition.

Of course, the travel itself had become so easy. The proliferation of new long-haul airlines, often subsidised by vain Middle Eastern plutocrats with bottomless pockets, ensured that transcontinental fares got lower by the year. The no-frills revolution, pioneered by the likes of EasyJet and Ryanair, transformed the once fraught and expensive decision of whether to go abroad into a momentary whimsy. A weekend in Paris? Rome? Vilnius? Now $60 return.

For my generation, this revolution of affordability and convenience was providential, coinciding with a time in life when we had the paltry wages and an absence of domestic responsibility to exploit it. The collapse of the old Eastern bloc, and its constituent nations’ subsequent tilt towards consumer capitalism, opened up the half of my continent where the beaches weren’t yet overcrowded and the beers still cost a dollar. In the meantime, the communications revolution meant that organising such trips had never been more straightforward. One spring, I arranged for a few friends to climb a Moroccan mountain over a long weekend. We flew to Marrakech on the predawn flight from Stansted Airport in London, where a dozen stag dos, bound to exact a very British carnage on Europe’s sybaritic capitals, were sculling tequila shots at 5am. Twelve hours later, we were 10,000 feet up in the High Atlas, readying ourselves for a 1am summit assault of Jebel Toubkal. I remember lying in the base-camp dormitory, giggling at the music of our farts brought on by the rapid change of air pressure, in a state of exultation. This kind of instant adventure, unimaginable just a decade earlier, was now just a couple of days’ wages and a few mouse clicks away.

As travel democratised, and became a component of millions more lives, a consensus grew that a storied life must necessarily be a well-travelled one. Holidays were no longer an occasional luxury, but a baseline source of intellectual and emotional succour. This idea of travel as axiomatic – as a universal human right – was a monument to an individualist culture in which the success or otherwise of our lives had become commensurate to the experiences we accrue.

And I was there, an embodiment of this new sacrament, and its amanuensis. In the proudest version of my self-image, I was a swashbuckling, bestubbled wayfarer, notebook in hand. ‘The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation,’ wrote Henry David Thoreau. Not me, no sir. Because I was a man who had been to 100 countries. Who knew what wonder was, and where to find it.

A decade or so ago, when I was approaching my 30th birthday, I went on a writing assignment to the Indian Himalayas, where I trekked for two weeks through the most beautiful countryside I have seen, before or since. I had a guide, a gentle man called Biru, and we spent most of the days walking in each other’s bootprints, chatting about the geography, the culture of the Bhotia people we encountered in the foothills, and the contrasts between our disparate lives. But one afternoon, on the approach to a 14,000-foot saddle called the Kuari Pass, I felt buoyed by some hitherto untappable energy, and I left Biru far behind.

As I ran, zigzagging up the mule trails, I suddenly became gripped with an extraordinary lucidity. It felt as if only now, with the last vestiges of civilisation 12 miles down the mountainside, did I have the solitude with which to grasp the true splendour of my surroundings. As I clambered from joy into reverie, a vision kept entering my consciousness – of a broad-shouldered man, beckoning me forward.

He sat on the pass, back propped against a hump of tussock grasses. He was just as the most precious family photos recalled him: the same age I was now, lean and smiling, in faded jeans and the threadbare grey T-shirt he wore on a sunny day in a south London park before he fell ill. He looked strong – not ghostly, but corporeal – and I remember being struck that he could look so beatific up there, seemingly inured to the brittle wind whipping up from the valleys below. I had a vague sense that if only I could get there, to the pass, we could stand shoulder to shoulder, and all the secret knowledge I had been denied – of how to live the life of a good man, of how to live unafraid – would flow from him into me.

At dusk, encamped at the base of the final approach to the pass, I felt hollowed out, bereft. After we pitched our tents, I walked a mile back down the trail and found a peaceful spot in a glade of tall deodar cedars, where I wept about my dad for the first time in years.

My most distressing childhood memories were, in fact, lurid dramatisations of events I’d never witnessed

In his book The Interpretation of Dreams (1899), Sigmund Freud described the death of a father as ‘the most important event, the most poignant loss in a man’s life’. I don’t know if that’s true. But I think I have always known that the first waymarker on my trip around the physical world was the same moment that upended my private one. According to the death certificate, that was at 10:30pm on 13 March 1985, when my father succumbed to non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in a London hospital, at the age of 32. Right from the start, the trauma of this event corrupted the way I processed and recalled experiences. Henceforward, my hippocampus would be a faulty and elastic device. I was four years old at the time of my father’s death. But I have no concrete memories between then and the age of eight.

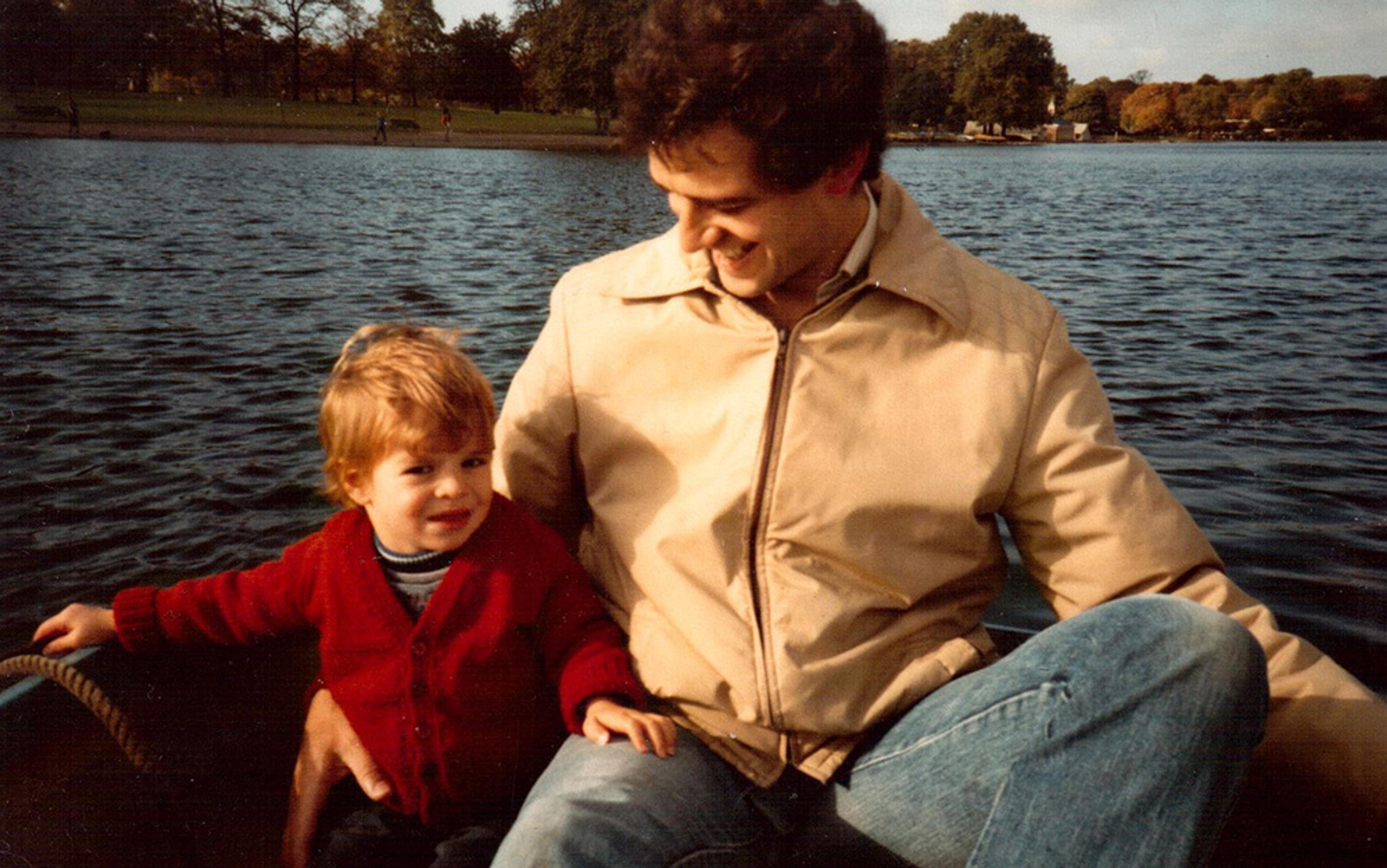

The author, aged three, with his father on Loch Lomond in 1984

Only in more recent years, in conversations with my mum, would I come to realise that my most distressing childhood memories – that is to say, those of my dad’s actual demise – were, in fact, recurring nightmares, lurid dramatisations of events I’d never witnessed. In the most indelible, I walk into a room of starkest white, my childish rendition of a hospital. Over in a corner, he lies dead and shrunken on a plinth. He has big purple welts over his eyes, like a melancholic clown. I can conjure this image with crystal clarity, yet my mum insists I was never exposed to his diminishment at the end, let alone his body when the fight was done.

Of the man as he was in life there is next to nothing. Just a sonorous voice, impossibly deep, my recollection of which is tactile as much as aural: a muscle memory of a reverberation I felt as I clung to his knees. What image I have stored has always been a spare composite, moulded around the gauzy recollections of those who loved him best. His friends and relatives would tell me: ‘Everyone adored Peter.’ And: ‘You are the spitting image of him,’ though this last wasn’t entirely true for, while I am tallish, he was a giant: 6 foot, 6 inches and broad, with feet so large he had to go to a specialist shop to buy his shoes. He was a sportsman, though one too laconic to take sports that seriously, and he was a talented artist, given to scrawling note-perfect caricatures on request. A self-possessed man, he had rebelled against the austere mores of a disciplinarian Maltese household, growing up to be kind, generous, egalitarian and wise. Oh, and he was also handsome, smart and preternaturally charming. An early death does not lend itself to balanced valediction, you see. Nonetheless, I was convinced of his perfection. Remember your dad: the fallen god.

This tendency to deify the absent parent – hyperidealisation – had left a haunting question unanswered: if the god was so mighty yet still succumbed, what hope was there for me? By all accounts, my perfect father had wanted nothing more than to live. It was fate, not choice, which had denied him that wish, and so I couldn’t trust fate at all.

I was in my mid-20s when I became convinced of the imminence of my death.

It would be too neat a story to suggest that I was always conscious of a direct causation between this dark fatalism and my early bereavement. As a child, fatherlessness was just the way of things, an ineluctable state of being which I accepted with the outward stoicism of one who knew no different.

However, as I neared the age he was when he died, I became transfixed by the expectation that my father’s destiny was mine as well. Just as I had internalised my relatives’ exhortations to step into his shoes – to be ‘man of the house’, custodian of my surviving family – I also expected to emulate his attenuated life-curve.

My days became backtracked by a hum of worry. I never saw anyone about it, and seldom if ever mentioned it to friends or loved ones. But reading around the edges, I suppose it resembled post-traumatic stress disorder, a miasma of intrusive thoughts, and vivid, almost hallucinatory, anxieties. At my most vulnerable, I felt hunted. Somewhere on the near horizon was a sickness, something to expose the weakness invisible to everyone but myself. I wasn’t sure what shape this chimera would adopt (probably cancer, in keeping with family tradition). But I knew it would be something enervating and rapid – a desperate withering. And I knew that I would make no peace with it, that I would endure every downward step in terror and the keenest fury at the injustice of it all.

Denied my precious years of formative complacency, knowing that it is all anguish and heartbreak in the end, I’d lit out to engrave my brain with random people and places, as if this alone were a barometer of self-worth. I might have kidded myself that it was just the pursuit of happiness. But, in reality, what I was embarking on was a project of temporal elongation, forestalling my death by bleeding each hour of moments. It just seemed like the best compensation for the years I was predestined to lose.

For the time that I lived in thrall to this self-inflicted prophecy, my overseas journeys provided respite for my restless mind. But the theatre of travel was changing, fast.

The paradigm shift made itself known in a new idiom: the ‘selfie’, bringing with it a disconcerting atmosphere of self-absorption to every tourist attraction and viewpoint in the world. ‘Digital nomadism’ debuted as an aspirational ideal, marketing the promise of professional success unconstrained by the geographical manacles of conventional, office-based work. The influencers hashtagged their way to fame and fortune. But somehow the transparency of their narcissism embarrassed whatever countercultural affect people like me were trying to cultivate. The retiree’s humble dream of saving for a ‘holiday of a lifetime’ had evolved into a ‘bucket list’, a life’s worth of checkable, brag-worthy aspirations. A poll in 2017 found that the most important factor for British 18- to 33-year-olds in deciding where to go on holiday was a destination’s ‘Instagrammability’.

Youth hostels that had once seemed like entrepôts of cultural exchange had instead come to feel like solipsistic hives, inhabited by people cocooned in the electric glow of phone and laptop screens. Travel had become egocentric, performative and memeified.

This new vulgarity appeared in tandem with travel’s exponential growth. The globalisation of English as a lingua franca was removing the enriching incentive to learn the local language. Smartphone maps meant you no longer had to ask strangers for directions. Sparking the locus coeruleus – triggering that synaptic lightning storm invoked by new experiences – had always been contingent on surprise. But now a glut of foreknowledge and the ease of forward planning was acting like a circuit breaker. What once seemed impossibly remote and enigmatic had been demystified. Pleasure cruises plied the Northwest Passage.

These reductive trends, both technological and cultural, were conspiring to dull the joy of visiting other places. The planet’s riches, which I’d once thought inexhaustible, seemed diminished, whittled down to a list of marquee sights, natural and human-made. Everything was too goddam navigable. Hell, perhaps I had just coloured in too much of the map.

It is perhaps indicative of my reluctance to plumb the origins of my travel addiction that it was only recently – while searching for some way to frame this idea of accumulating experience to fill a void – that I came across the work of Daniel Kahneman. An Israeli psychologist and Nobel laureate, Kahneman is renowned as the father of behavioural economics. The writer Michael Lewis calls him a ‘connoisseur of human error’. Some of his most intriguing theories have been in the field of hedonic psychology, the study of happiness.

Over decades of research and experimentation, Kahneman identified a schism in the way people experience wellbeing. In his bestselling memoir, Thinking, Fast and Slow (2011), he articulates this dichotomy in terms of the ‘experiencing self’ and the ‘remembering self’. The experiencing self describes our cognition as it exists in the ‘psychological present’. That present, Kahneman estimates, lasts for around three seconds, meaning an average human life comprises around 600 million of such fragments. How we feel in this three-second window denotes our level of happiness in any given moment.

The remembering self, by contrast, describes how the mind metabolises all of those moments in the rear-view mirror. The sensation resulting from this second metric would be best described, not as happiness, but rather ‘life satisfaction’.

Kahneman’s crucial observation was that the way we recall events is invariably divorced from the experience itself. One might expect the memory of, say, witnessing the Northern Lights to directly correlate with our feelings at the time – to comprise an aggregation of the experiencing self’s emotional responses to sensory stimuli. Instead, the remembering self is susceptible to all kinds of ‘cognitive illusions’. In its urge to weave discrete experiences into a desirable narrative, the memory will edit and elide, embellish and deceive. The actual sensations, and, by extension, our true sense of how we felt, are lost forever. We are left with only an adulterated residue. ‘This is the tyranny of the remembering self,’ Kahneman wrote.

The narcissistic atmosphere of the selfie age had exposed the solipsism of my own quest

This revelation held import for all manner of human experience. (Kahneman’s most famous illustration of the divergence was an experiment involving colonoscopies, which I will refrain from describing.) But it seemed to have particular implications for the valence of holidaymaking, and the travel-oriented ambitions I and others had opted to pursue.

For years, I’d been convinced that the mnemonic quality of novel experiences presented a route to happiness. The philosophy that I had come to live by – that chasing new horizons produced a more colourful tapestry in the mind, and that this could be cashed in for contentment – had seemed self-evident. But, according to Kahneman’s hypothesis, the calculus was at least partly illusory. Was experientialism a legitimate route to wellbeing? Or was it just a function of my storytelling impulse, my urge to portray my life as a battle to outrun a prophecy, and thereby prone to novelistic biases that I was helpless to regulate?

In the meantime, I knew, other important sources of happiness had been neglected. I had let friendships lapse. I had scorned any inclination to sustain a sense of belonging at home. I had driven my partner, Lucy, to distraction with my pathological need to shape the calendar, not to my mention my mood, around coming foreign capers. Yet I was no longer sure that I had been honest with myself about how necessary it had all been. I suspected that one of the reasons I was so disconcerted by the narcissistic atmosphere of the selfie age was that it had exposed the solipsism of my own quest. For while I balked at ‘influencer’ superficiality, I also appreciated that my travel writing was just a more sophisticated version of the same tendency. I wondered how many other people might have been using travel in a similar, medicinal way – to curate a narrative, sometimes at the expense of subjective joy.

It didn’t help that tourism was assuming more ethical freight. Renewed calls to decolonise the Western mind called into question the rich world’s entitlement to tramp through poorer lands. The relationship between travel and ecological destruction solidified. Air travel, in particular, dwarfed almost every other activity in terms of individual carbon emissions. Suddenly, there seemed to be an irreconcilable hypocrisy about someone who yearned to see the world, but whose actions contributed to its devastation.

By the time COVID-19 interrupted the trajectory, it was no longer possible to sustain the masquerade that travel was, by definition, an ennobling endeavour. The traveller had mutated from a Romantic ideal of human curiosity into something tawdrier: a selfish creature pursuing cheap gratification at the cost of everything. A mammal that fondled the coral reefs while driving the ocean acidification that could wipe them out. The desire to see foreign places had come to seem like just another insatiable and destructive human appetite, its most feverish practitioners a dilettante horde, pilgrim poseurs at the end of time.

There was no way to avoid a reckoning with the egotistical underpinnings of my own itinerancy. After all, what was I if not the archetype of the vainglorious traveller, a moment collector for whom learning and pleasure were incidental to my quest for affirmation? And, of course, I was an agent of the demystification and cultural homogenisation I deplored, writing about places that might have been better off left alone. (By this time, the Thai island where they filmed The Beach, a magnet for tourists after the film’s release, had been closed to visitors, a scene of ruin.) Journeys that once felt carefree were now tainted with remorse, as I realised that my dromomania could so easily be reframed as a kind of consumerist greed.

‘Every time I did these things, a question arose about the propriety of doing what I was doing,’ wrote Barry Lopez in Horizon (2019), his recent meditation on travel and natural communion. ‘Shouldn’t I have just allowed this healing land to heal? Was my infatuation with my speculations, my own agenda, more important? Was there no end to the going and the seeing?’

There seems no way of divining what will become of our compulsion to wander

Of course, there was an end, or at least a pause. A pandemic saw to that. The coronavirus lockdown, which came into force in my home country of England on 26 March 2020, precipitated the most static period of my adult life. But by then, truth be told, my manic period of travelling was already behind me.

If death had been the poisonous kernel of my fatalism, new life would provide a cure. My daughter, Lily, was born in 2012; a son, Ben, followed three years later. It is counterintuitive, I suppose, that the rise in stakes that attends a child’s dependence should have pulled me clear of anxiety. But then, too, parenthood brought with it an obligation to prioritise other lives over my quixotic search for self-validation. These years, during which I surpassed the age my father had been at the time of his death, provided milestones of a more meaningful escape.

Travel became less essential. I began to revisit places I loved and reconciled myself to the idea that there were places I would never see. I no longer slept with an envelope of travel documents – passport, bank notes, immunisation certificate – at my bedside. In this way, lockdown was a coda to a process of divorce already underway.

The urge to move still lingers. Even as personal choice and external circumstance steer me towards domesticity, some fragment of my character will always be that scared mouse, a novelty junkie struggling to replicate the circumstances of my early highs, forever burdened with the unfortunate knowing of someone who has seen his first everything. But the imperative has lost its desperate edge. In the wake of a pandemic, which torpedoed the various overseas assignments I had on the slate, this has transpired to be no small relief.

For the time being, there seems no way of divining what will become of our compulsion to wander, no clear indication of whether this pause represents an eclipse or an extinguishment of travel as it was before. If there is any lesson to glean from my journey, it is that a fixation on experience is like so many other addictions: gratifying, intermittently euphoric, but ultimately forlorn. Travelling is wonderful, don’t get me wrong. But it is not the same as contentment.

This Reebok shoebox, I think, as I place the miscellany back inside it, is a treasure chest of an innocence that may never be recaptured. And that may not be the worst thing for the planet, or the priorities of the people who cherish it.