‘Death is the dark backing that a mirror needs if we are to see anything.’ Saul Bellow, Humboldt’s Gift (1975)

As the Apache attack helicopter took off, with Captain Dave Rigg strapped to it, he realised that, in the four months he’d been in Afghanistan with the British Army, he had not yet fired his weapon. To test that it still worked, Rigg let off a few rounds in the general direction of the Taliban fort ahead, provoking an immediate, angry response from the pilot on the other side of the cockpit windscreen. Less than an hour earlier, Rigg had volunteered for a hastily planned and highly dangerous mission to recover a Royal Marine missing in action (MIA) after an attack on the same fort that morning. The daring mission successfully located the missing Lance Corporal Ford, however, tragically, he had already been killed, most likely in the earlier attack. For his part in the rescue attempt, Rigg later received a Military Cross.

I met Rigg in a pub on the banks of the River Avon in Bath. With its ordered Georgian crescents, thermal spa and tea rooms, the setting could not have been further from the chaos of the medieval-looking Jugroom Fort on the banks of the Helmand River, where the two Apaches had landed in a dust storm thrown up by the rotary cannon of a US Air Force A-10 jet providing close air support. He modestly told the story of a day he is unlikely to forget, gently chastising himself over things he believes he could have done better.

When I asked if the mission would have gone ahead if they’d known that Lance Corporal Ford was already dead, Rigg answered ‘Yes.’ Would he have wanted others to risk their lives to recover his body if it had been him? He answered ‘No.’ Rigg paused to consider the potential contradiction, and added that in this hypothetical situation it would not be about him. There would be more at stake. For him, the fact that the British military recover their own, alive or dead, is integral to what makes it the organisation it is. But why should accounting for our missing be so important that it is worth risking more lives for? This is a question that, as a former soldier myself, I find puzzling but important.

While conducting research on a different project in the National Archives near London, I came across a folder entitled: ‘Italy: 1st and 2nd Battalions, Rifle Brigade; missing personnel – 1943 Dec 02 – 1945 Nov 09’. The first documents were official communications looking for answers on the whereabouts of four personnel, ‘all good soldiers, showing conduct of a high degree both in and out of the line whilst in action’ who ‘were not likely to desert, and further, there was no opportunity of doing so’. These official documents were followed by scores of letters, from the soldiers’ comrades and official investigators, trying to piece together what had happened to them.

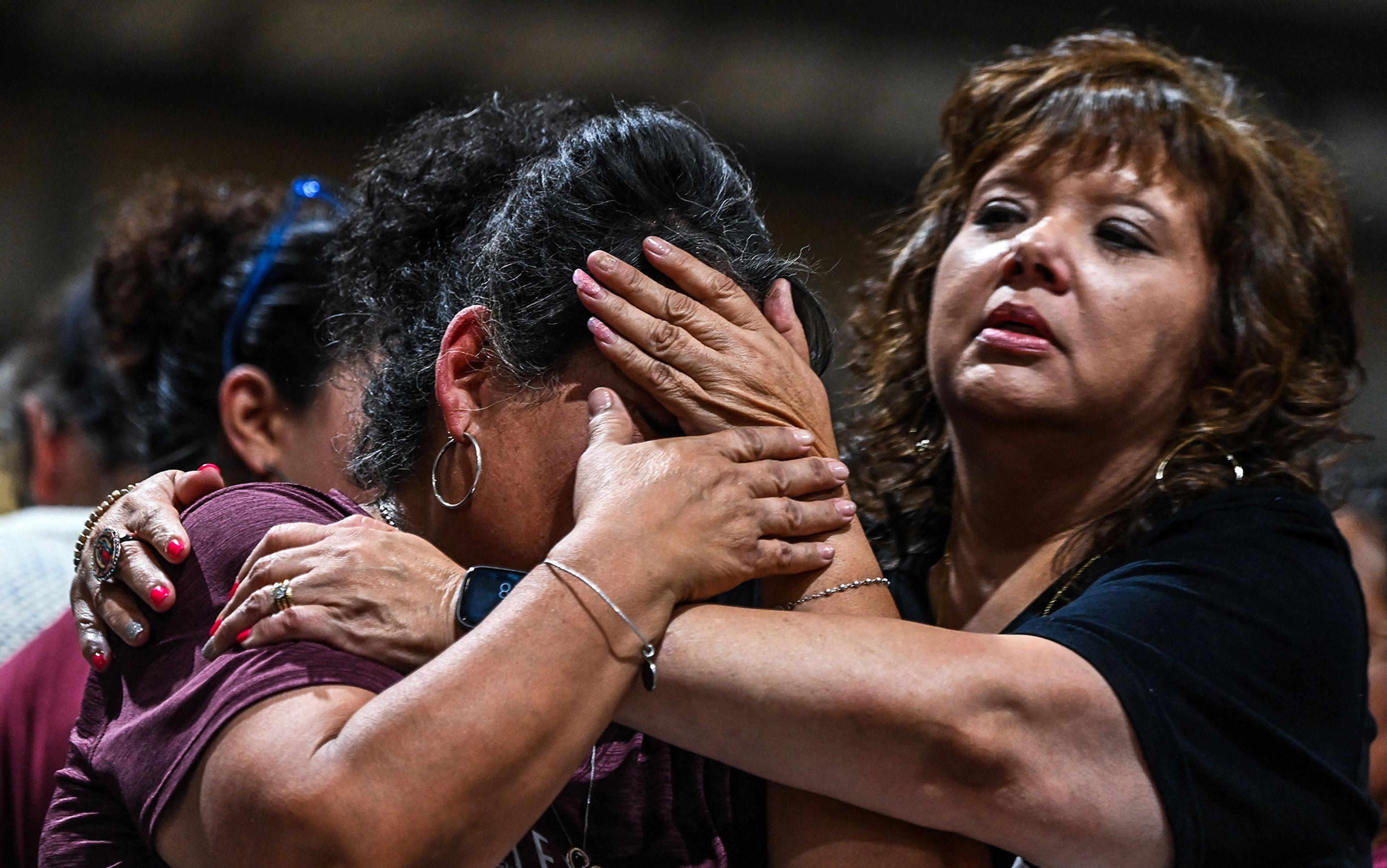

The war in Italy had been over since the spring of 1945, but no one knew where those missing soldiers were. They had not appeared on casualty lists, nor were they on the lists of prisoners of war, and they were not thought to have deserted. They had disappeared into the fog of war. Sitting in the archives more than 70 years later, having served in conflict myself, and considering what it might have been like for my own parents, this seemed in some ways a worse outcome for their families than receiving confirmation that they had been killed. The US psychologist Pauline Boss, who started working with the wives of missing US airmen in the 1970s, writes that ‘even sure knowledge of death is more welcome than a continuation of doubt’, and describes incomplete or uncertain loss as ‘ambiguous loss’.

People aren’t meant to just disappear. Disappearance can expose an existential fear in those left behind – what could make you question your self-esteem more than the knowledge that you could just go missing without a trace? This is why some states and armed groups have deliberately ‘disappeared’ those seen as their greatest threat: during the Troubles in Northern Ireland, for example, supposed informers on the paramilitary organisation the IRA were at risk of vanishing. As a character in Jez Butterworth’s play The Ferryman (2017) points out, denying information or giving false information can add to the pain of loss, and is a particularly cruel way to treat the living:

Sure a kneecapping hurts. Even with a death. There’s a body. She can grieve. In time the pain finds a home. But take a man out to a bog in the middle of nowhere. Put a bullet in his head. Then send friends to tell her they’ve seen him. On a ferry to Liverpool. The horses in Wicklow. Give that woman hope. Keep the wound open.

Today, the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency in the US spends more than $100 million a year in the effort to find the 83,000 individuals still missing from the Second World War, and from the wars in Korea and Vietnam. The majority of these MIAs are certainly dead, but the search continues at great cost, to find their remains and repatriate them. This organised response is relatively new. Before militaries developed the administrative and technical capabilities to conduct such searches, it was down to the soldier’s comrades or even their families to find the missing, most usually by combing the battlefield after the fighting had ended.

Not knowing seems unthinkable: we are used to answers at our fingertips

The Ancient Greeks would recover their fallen, cremate them, and return the ashes to their families. An empty bier or coffin frame was carried by returning soldiers through Athens to represent the missing. King Harold’s common-law wife Edith the Fair walked through the grisly aftermath of the Battle of Hastings to find his body by identifying scars only she would recognise, so he could be given a Christian burial. A royal survey of 1389 demonstrated the number of people who in peacetime had membership of a confraternity or guild, to which a weekly subscription was paid, so that if you died away from home your fellow members would bring your body back.

In our interconnected world, where you can log on and see what someone you went to primary school with had for breakfast, the idea of not knowing what’s happened to a loved one seems unthinkable. We are used to having the answers at our fingertips, search engines take us to forgotten facts, and clouds hold images from millions of misremembered memories.

Yet people go missing every day, and not just in wars. Natural disasters occur, pandemics overwhelm the state’s ability to account for people, wars still rage, and sometimes people just decide to walk away. According to the charity Missing People, 180,000 people go missing in the UK every year. The UN’s International Organization for Migration recorded 3,139 migrants killed trying to cross the Mediterranean into Europe in 2017; in many of these cases, no official confirmation would get back to their families. Those fleeing wars in the Middle East and Africa are making similarly perilous journeys today, and some of them will never be heard of again if something befalls them en route.

There are some common themes across time and cultures that make what Boss calls ambiguous loss – the loss of the missing, a loss that has never been fully confirmed – so difficult. One is the inability to perform the appropriate rituals or rites that help us manage loss. In Homer’s epic poem The Odyssey, a tale of a soldier missing in action from the Trojan War, Elpenor confronts the visiting Odysseus in the underworld, pleading with him to return to the witch Circe’s island to find his undiscovered body, and perform the correct burial rites so that he can pass from limbo on the wrong side of the river Styx.

And in Homer’s epic poem The Iliad, a grieving Priam stands on the territory of Troy asking himself if his son Hector, whose body Achilles has taken, had really existed. The importance of giving the correct burial rites to the dead is also central to Sophocles’ play Antigone. Meanwhile in the Middle Ages, soldiers at the battle of Agincourt would have expected to be gathered up from where they had fallen and taken for burial in their own lands, where their kin could focus their prayers on guaranteeing the right passage to the afterlife. A few kilometres from Agincourt, 500 years later, soldiers dying at the Somme in the same mud of Flanders would have expected different rituals. For many, the immortality of an afterlife was being replaced by the immortality of being remembered by the nation. The Thiepval Memorial to the Missing of the Somme bears the names of more than 72,000 soldiers who have no known grave. The immense psychological suffering caused for their loved ones by the absence of a body to bury or cremate is hard to imagine.

During the brutal reign of Pol Pot in Cambodia when religious practices were banned, families developed new rituals to cope with the mass executions that saw bodies dumped in vast burial pits, to avoid their loved ones being stuck at the wrong spiritual level. Such rituals, of course, also help the living to move on. A case worker from the UK charity Missing People told me of the countless times he has seen families keeping the rooms of the missing exactly as they left them. The physical limbo of the room reflects the psychological state of not knowing, when it is not clear whether relatives should mourn or keep hope alive.

We need to make sense of our lifespan with fictional stories that have an origin, a middle and an end

These rooms can also act as a form of memorial to the families, a place they can visit and reflect on the missing. Missing People has improvised an annual ceremony that ends with tying messages to the missing to a tree of remembrance in a park in Richmond near London. Many of the families that Missing People supports have loved ones who have chosen to go missing, complicating the emotional response generating more questions that are left unanswered. There is a certain fascination with a sub-group of those, such as Lord Lucan and Osama bin Laden, who deliberately disappear after committing crimes. The longer they continue to thwart large-scale attempts to find them, the greater the level of interest. When their fate is known, the fascination diminishes.

In The Sense of an Ending (1967), the British literary critic Frank Kermode investigates our need to make sense of our lifespan with fictional stories that have an origin, a middle and an end. ‘What puts our mind at rest,’ he writes, ‘is the simple sequence.’ Stories have always helped make sense of our world, and our tragedies within it. We are ‘Homo fictus’, as the US scholar Jonathan Gottschall puts it in The Storytelling Animal (2012). He argues that stories have a universal grammar, much as Noam Chomsky claims is shared by all human languages, and writes:

No matter how far we travel back into literary history, and no matter how deep we plunge into the jungles and Badlands of world folklore, we always find the same astonishing thing: their stories are just like ours. There is a universal grammar in world fiction, a deep pattern of heroes confronting trouble and struggling to overcome.

With the missing, this universal grammar is not followed. There is a tick but no tock. Our stories situate us in a place and a time, locating us in the wider story of human history, stretching along from the distant past to an open future.

When humans tell stories, we place a great emphasis on the ending. But when there is no news, the mind has to compensate. In 2011, a massive earthquake sent a towering tsunami towards the Japanese coast. It surged inland creating carnage in its wake. Almost 20,000 died. Survivors of the disaster soon began seeing and feeling ghostly presences; people dressed in warm clothes at the height of summer, hailing taxis and then disappearing from the back seat.

Jikisai Minami, chief priest at a Buddhist temple in Japan, makes an interesting distinction with relevance to the cases of the missing. Speaking to the historian Christopher Harding at Edinburgh University, he distinguishes the ‘real’ from the ‘virtual’. The ‘virtual’ is what can be switched on and off, something you can also choose to put out of your mind. The ‘real’ is different: the person is there, like it or not, not necessarily as a physical presence, but in your thoughts and your interactions with others. Someone who is missing can be ‘real’ whether they have been killed or have survived. Minami suggests that we should engage with those that remain ‘real’ directly.

Perhaps families of the missing can take something from this, and engage those that are not present physically in this same way; follow through on known wishes, ask for advice, and say goodbyes that were never said. Boss, author of Ambiguous Loss (1999), recalls interviewing the wife of a pilot who mentioned that her husband had visited her twice since he went missing. The first time, he gave instructions for what to do with the house and the children. A year later, he returned to say she had done a good job and to say goodbye. This was when she knew he was dead. Conversations with her missing husband comforted and reassured her.

Throughout history and across cultures, where we find examples of the missing, we also find thinkers and writers who can offer possible consolations. Those that came before us didn’t have our instant communications or social media’s constant updates, which perhaps mean that we are even less well-prepared to deal with the not-knowing today. So it makes sense to look to those who lived with and accepted such uncertainty. From Ancient Greece and Rome, there are the Stoics. In Seneca’s consolation letters to grieving friends, he advises them to let go of what they cannot control and focus on what they can, to cease tears that cannot bring back the dead or find the unfindable. Meanwhile, Epictetus gives us the idea that we don’t own things or people, they are simply lent to us by the Universe.

We should rejoice in the brief flight without knowing the precise moment when the sparrow exits the hall

From the dust of its stars, the Universe fashions gifts to us, so precious that we may only enjoy them for a short time before we must return them. Death ends the loan, but so can distance, political barriers, or changing beliefs and allegiances – all of which can cause someone to be missing from us. The Stoic acceptance of this is mirrored in modern psychology where acceptance therapy can be used to treat ambiguous loss.

Medieval ideas of the transitoriness and impermanence of the material world, as expressed in the Old English epic poem Beowulf, challenge our notions of continuity and desire for certainty. We this find in Bede’s image of a sparrow flying from the winter darkness into a lighted hall, into the warmth and cheerfulness for a moment, then out once more into the night, which to Bede symbolises the span of a life. Light follows dark, then dark follows light. We should just rejoice at the warmth and cheerfulness our brief flight allows us. We don’t need to know the precise moment the sparrow exits the hall. Taoist thinkers emphasise the cycle of the seasons, and the wider cycles that the seasons fit into, as central to many key concepts and ways of understanding the world, challenging the linear notion of our stories’ arc that puts so much stock on the ending. And the American pragmatists’ view that an idea or belief has value not because it is true but because it is useful can help us to rethink how we view religious practices and consolations, and allow them to be of use even to those who don’t believe.

We cannot know what the families of those Second World War riflemen missing in Italy used to console themselves as they waited and waited for the arrival of the telegram. They would have been unsure whether they should even call themselves wives or widows or, in the case of a grieving father or mother, what to say about how many children they had. For the families of all, release from limbo did eventually come, as I realised when I got to the bottom of the file. All the soldiers would eventually be confirmed dead in fighting in and around the village of Tossignano in December 1944. Not all their bodies were found, though.

When the journalist Earl Swift asked the family of a missing US airman from the Vietnam War, whom they knew was undoubtedly dead, why they wanted the expensive search to continue, they said because it showed that he still mattered: ‘It’s the intent of the effort, not whether it succeeds or fails.’

The investigative psychologist Karen Shalev Greene is the director of the Centre for the Study of Missing Persons in Portsmouth, UK. When she speaks with overseas governments that make little or no attempt to search for missing persons, she tries to hold up a mirror to show what a society looks like when it doesn’t search for its missing. Echoing the language used by Swift’s interviewee, Shalev Greene told me that, when dealing with missing-person cases, ‘every person matters’. I think this is what Rigg referred to when he spoke about what sort of organisation the British Army wanted to be – an organisation where its people matter. As much as the military can define itself by how it recovers its fallen, how we deal with our missing people can define us as a society. If the end of your story is not known, if everyone gives up trying to find what happened to you, there is a sense that you did not matter. I want to live in a society where everybody matters.