My greatest fear growing up in the wilds of the French countryside, south of the Loire Valley, was that my English mother would speak to me in her native tongue and do so loudly. I could just about forgive her wilting straw hats and translucent dresses – when the phalanx of local mothers at the school gates wore wipeable smocks spattered with mud, wine or tomato juice depending on the season – but I would wince when she used English outside the home. On the way back from school, along the vineyard tracks, even with my peers well out of earshot, I felt I could hear my mother’s cut-glass English ricocheting off the rocks.

The linguistic equilibrium of my childhood was held in place by numerous artificial partitions. English was the language spoken within the four walls of our home. French was for school, and generally everything outside the family – except that it was also employed for individual conversations with my brothers. Then there was Italian – a language I associated with my father, and which I confined to regular visits to Italy, and the impassioned Neapolitan love songs played at window-shaking volume in the car.

Underlying these linguistic demarcations was my need to stay camouflaged whatever the backdrop. On trips to England to visit my mother’s family, I kept my French under wraps; in Italy, I stuck to subjects I’d mastered well, in case an errant English or French vowel exposed me as a fraudulent hybrid. Safe identity was a three-sided mask.

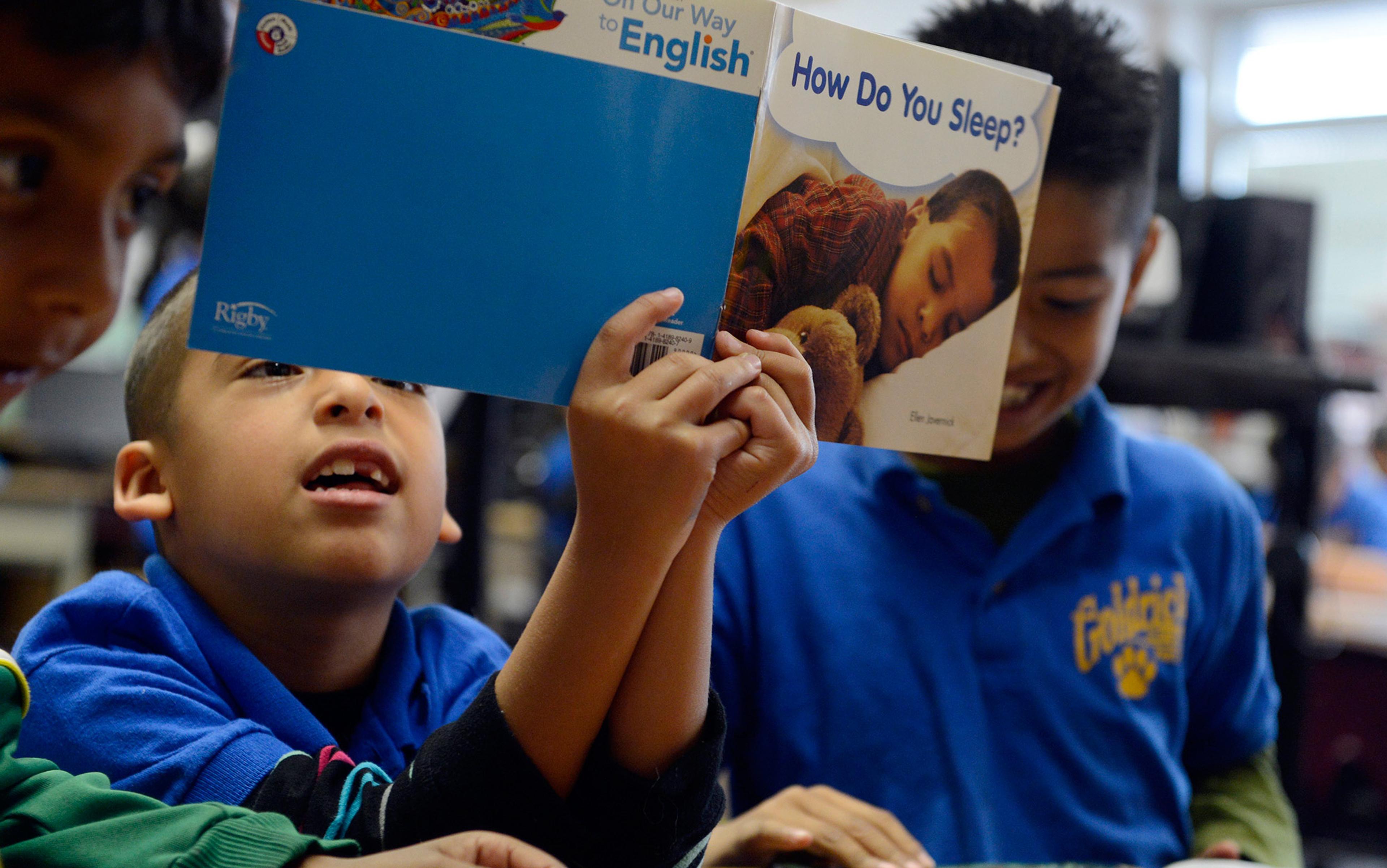

When I became a father myself, I assumed that speaking to my London-born children in French, from the moment they were born, would naturally make them bilingual. It didn’t. Nor did surreptitiously setting all our DVDs to the French-language option, or reading them my old copies of Asterix and Tintin at bedtime. I’d always fondly pictured myself conversing with my children in French. And in my fantasies, with the help of cousins, Italian was also going to graft itself organically on to my children’s French and English, and the linguistic ménage-à-trois of my upbringing would be replicated.

Introducing French into the family equation has undoubtedly been an additional complication. It skews mealtimes, often setting off lopsided conversations, pitting my French against everyone else’s English. It makes the children feel they are being judged and tested. And, despite their growing comprehension of French, they’ll find any excuse to walk a few steps behind me on the way to school in case I’m overheard. They stick their fingers in their ears when the Petit Nicolas CD is played in the car. They wriggle their way out of talking to French-speaking friends and family members by perfectly mimicking Gallic shrugs, sometimes accompanied by Parisian-sounding ‘errrrs’, or else they clam up completely. Most of their conversations end up wordless. A thumbs-up or a thumbs-down, offered with a cherubic smile, usually settles a wide range of issues.

Would it have been different if our children had gone to a French school or if we had lived in a French-speaking country? It’s not that clear-cut. The ingredients of home, environment, culture, regular practice, schooling and motivation need to meld together within a linguistic cauldron, over a sustained period, for a language to take lasting root. My British wife’s grandmother grew up in an expatriate family in China and spoke Chinese up to the age of 13. After returning to England, she lost the language entirely.

My children are not in the eye of converging linguistic influences the way I was. I have to accept that I cannot recreate the natural intermeshing of languages necessary for long-lasting bilingualism or multilingualism. I have, disturbingly, even begun to fear that my children might not speak any language other than English.

From school to university, and then working and travelling for a UN agency for many years, I constructed myself thanks to different languages, following the roads they paved out into the unknown. I can now say with confidence that the chameleonic battles of my childhood were worth it. A knowledge of languages can foster versatility, an attentiveness to the world and an understanding of cultural difference. It can make sense of the make-up and narrative of nations, cultivating deeper and joyous communion with others. Without languages, I feel as though my children are going to be missing some vital limb, hobbling through life, cut off from their heritage and the possibilities of the world.

Witnessing my difficulties, an Italian friend in London recently suggested that I should just give up on another language for my kids. English, he pointed out, now has impregnable status across the globe. What use is there in an Anglophone child learning another tongue when close to 2 billion people speak English already? The standard conversation nowadays between business people, be they Russian, Peruvian or Egyptian, is in English. It is the language most tourists employ. It is what schoolchildren the world over are studying. On our family holidays abroad, English must have indeed seemed like some sort of magic, cross-national master key to our children; in Spain, Turkey, Greece and Switzerland, shopkeepers and hoteliers addressed us in English, without even enquiring where we came from.

A minimal level of English is now almost universally accepted as a basic prerequisite of any education. For many, this is on top of a mother tongue, another language and more. Where, though, does that leave the monolingual native English speaker? The fact that native speakers are already greatly outnumbered demographically by non-native speakers is shifting the dynamics of English dramatically. My Italian friend’s vision of an English-only future for my children poses numerous problems.

The monolingualism of many parts of the United States, Australia and Britain – where rates of foreign-language study at university and school level mostly continue to fall – is far from the international norm. Bilingualism and multilingualism are everyday features of life in a whole raft of countries. In Morocco, many teachers I used to work with could skip with ease from the dialectal Arabic, Darija, to standard Arabic, and then to one of the various Berber languages, and then French. India, according to the Ethnologue website, has 461 languages, Papua New Guinea has 836 languages, and Cameroon has 280. In Scandinavia and the Netherlands, it is taken for granted that English is learned from an early age alongside the mother tongue. In Lebanon, many people naturally weave Arabic, English and French into all conversations.

There was a time in Britain, during the 1970s, when nurturing bilingualism or multilingualism in young children was actively frowned upon. It was perceived as confusing for intellectual development and language acquisition. I have several friends of mixed heritage who lost out on being bilingual because of this thinking. The exact opposite approach is recommended today. Studies by the Department of Theoretical and Applied Linguistics at Cambridge University appear to show that bilingual children have a distinct advantage over their monolingual peers in their social interaction, cognitive flexibility and awareness of language construction. Research by the psychologists Ellen Bialystok and Michelle Martin-Rhee at York University, Toronto, also noted this boost to cognitive abilities. Their 2004 study of pre-schoolers showed bilinguals eclipsing monolinguals when given tasks with conflicting visual and verbal information.

those who spoke two languages developed dementia an average of four and a half years later than the monolinguals

In another study, in 2007, Bialystok and colleagues went further and looked into the impact of bilingualism on a group of 400 patients with Alzheimer’s. It was observed that those who were bilingual were better able to function with the effects of the disease than their monolingual peers; the impact of the disease appeared tempered. A study in 2013 led by researchers from the University of Hyderabad and the University of Edinburgh centred on Alzheimer’s sufferers in the multilingual Indian city of Hyderabad. The research team assessed 648 people, of whom 391 were bilingual. Their results seemed to suggest that those who spoke two languages developed dementia an average of four and a half years later than the monolinguals. Cognitive multitasking arising from speaking more than one language was deemed to act as protection.

In my experience, learning another language lays the foundations for greater curiosity and openness to learning processes overall. It evolves into a curiosity that can underpin life in general. As a child, no doubt because of my rural isolation too, I used to spend hours crouched in the long grass observing insects and juxtaposing words in my head, lining up meanings in different tongues, jostling alternatives and options, classifying, rearranging. I remember being particularly exercised by my father’s complaint that there wasn’t anything as expressively satisfactory as the French ‘tant pis’ in English. ‘Too bad’, ‘never mind’ or ‘oh well’ didn’t quite do it justice, and the accompanying gestures certainly weren’t the same either.

This sort of linguistic arithmetic was vital when I later worked in Japan for a number of months and tried to grasp the rudiments of a totally unrecognisable language. It also fed into a period studying Arabic. I came away with a very stunted grasp of the language, but I was aided by the fact that an adaptability with words had long been part of my modus operandi. I never had auxiliary verbs, adjectival agreements or the subjunctive drummed into me at my multi-grade village school in France, but I had absorbed such mechanisms unconsciously, and this seemed to provide constant leeway.

Elderly Egyptians recount how in Alexandria, in the early 20th century, they would switch between Arabic, French, English, Italian and Greek, depending on what they were doing and whom they were addressing. Multilingualism was a way of life for many, a shared culture. New York in the 19th century had up to seven different Yiddish newspapers, as well as others in Italian, Swedish and German. Like America as a whole, the city was once home to rich pockets of linguistic difference before their gradual dissolution into the national melting-pot. From Jakarta to Johannesburg to Los Angeles, whole tranches of society in today’s mega-cities still dip in and out of different tongues. Twittersphere language maps of New York and London display this remarkable array of tongues; behind their technicolour streaks, the confluences of commerce, immigration and tourism twist and mingle, sweeping languages along with them.

A Syrian friend who is fluent in five languages – Arabic, English, French, Greek and Spanish – keeps the Levantine tradition of polyglotism alive. She explains that she generally employs English for work; French for friendships and political discussions; Spanish for music and relaxation; Arabic for home, family and swearing; and Greek for holidays. For her there is a reassuring elasticity to having constant alternatives – the interchanging of cultural personas becomes possible.

Every language provides an inimitable prism through which to interpret human experience. At the time of Nelson Mandela’s recent death there was much talk of ‘ubuntu’, a Nguni Buntu word which can be broadly reduced to a concept of shared humanity or fellowship with other humans. It doubtlessly means much more to those who understand Nguni Buntu and its related languages. Countless tongues have a similarly rich palette, which escapes strict translation or elucidation. Speaking another language is the only true way to grasp this fullness.

Of course, the way in which speaking another language opens up not just new words and cultures but also produces a particular mindset can be the stuff of clichés. The stereotype is that German creates a greater propensity for music, Mandarin better shapes the mind for maths, French or Italian are for love and poetry, English is for pragmatism and business, and so on. The story goes that the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, spoke Spanish to God, Italian to women, French to men, and German to his horse. My Syrian friend might say that it is precisely the lack of confinement to one language that allows one to escape any commonplace definition by it. Freedom speaks many tongues.

Areas most vulnerable to the loss of biodiversity are regions where languages are dying out

Language caused mayhem with the loyalties of my childhood because the frontiers I tried to dig in around my identity were untenable, and led to internal conflict. A Catalan, Basque or Kurd would, no doubt, have much to say on the subject; a mismatch between official language and home language, for one, creates asymmetry, turning schooling into a likely source of grievance. The Berbers of North Africa, the indigenous groups of Latin America are just some people who have suffered from such one-sidedness. The history of nation-building is littered with linguistic pain: the suppression of French in Louisiana in the 1970s and ’80s, the crushing of Breton in France after the First World War, the curbing of Welsh in the 19th century, the continued stifling of Aboriginal languages in Australia.

The nexus between language, culture and identity makes the linguistic diversity of the world all the more precious. UNESCO estimates that more than half the world’s 6,000 or more languages could be extinct by the end of the century. Every language, particularly indigenous languages, are reservoirs of untapped knowledge, and when a language ceases to be spoken, irrecoverable wisdom – in areas of medicine, science, agriculture and culture, along with unique ways of viewing the world – rapidly disappears. The Hans Rausing Endangered Languages Project, supported by the School of Oriental and African Studies in London, carries the chilling rallying cry ‘Because every last word means another lost world…’

In a working paper entitled ‘Indigenous Languages as Tools for Understanding and Preserving Biodiversity’, UNESCO points to a study of the Amuesha tribe of the Peruvian Upper Amazon that directly linked the loss of native speakers to a fall in the local diversity of crops. Studies by Penn State University and Oxford University, published in 2012 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, also highlight a relationship between the accelerating disappearance of plant and animal species and the predicted loss of the world’s languages. Areas most vulnerable to the loss of biodiversity are regions where languages are dying out. More than 4,800 of the world’s languages are concentrated in zones of high biodiversity.

English in its global pidgin is escaping native speakers and morphing into a shapeless jargon-filled smoke that has no real name or ownership

Languages splinter and Creolise constantly, but their current quickening rate of extinction is a cause for real concern. The blame can’t just be placed on the continued spread of English. It is more that the forces of globalisation that have brought English on their coattails tend to run roughshod over plurality and localism. Behind the hegemony of English comes the starkness of a new dawn where cultural specificities and the practices of minorities risk being levelled out. And the language attached to that blandness is increasingly international English: globalisation and English are in a symbiotic embrace.

The kind of hotel signs that amuse native English speakers abroad – ‘In case of fire please alarm all the guests’ or ‘Do not have children in the swimming pool’ – have ramifications that are not so innocuous. English in its global pidgin is not only escaping native speakers but morphing into a shapeless jargon-filled smoke that has no real name or ownership. Historic English, with its accumulated layers of maturity, has unwittingly spawned a rootless and pragmatic derivative that is inexorable in its unfolding, sucking the texture out of the very language that gave it birth, and impoverishing other tongues along the way. In the way that Ikea replicates furniture the world over, this global English Lite, aided by the ubiquitousness of technology, is eliminating particularity and fertilising sameness.

A few years ago, Jean-Paul Nerriere, a former marketing executive at IBM, formulated a boiled-down English for non-native speakers he called ‘Globish’ (in characteristic Globish fashion, the term has since propagated). Unlike artificial languages, such as Esperanto, Globish is considered a practical tool rather than a new tongue. It feeds off a very restricted but existing terrain of words shared by non-native speakers of English. The future for English as world lingua franca might be something similar: a watered-down or mongrelised user-friendly offshoot where nuance and lyricism are redundant.

And yet, paradoxically, the universality and, ultimately, the growing banality of global English might lead to other languages eventually emerging from its shadows. This will hopefully give renewed vigour to multilingualism and bilingualism, or, at the least, just vary language-learning once again. Ironically, and despite the many predicted technological hiccups, speech-to-speech translators – successors of Babel Fish – might also create new openings in the world’s linguistic landscape. NTT Docomo, a Japanese telecoms operator, in particular, is said to be developing instant translation glasses in time for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics to allow two-way translated conversations in real time. They might yet provide fresh breathing space for linguistic diversity, an opportunity to revalidate the innumerable ways of expressing the world.

I cannot deny the utility of English, or its role in today’s interconnected world. Its preponderance, though, doesn’t divest my children of the need to speak other languages. On the contrary, the rise of global English will require native speakers to engage further with foreign languages. Unless I act, my children will have absolutely no linguistic edge at all compared to billions of others who master English as well as their own languages, and more.

Making sure my children are at least proficient in conversational French is a goal I have set myself despite the setbacks. A recent event has given me reason for hope. At a market in London’s east end, overhearing excited shouts in French, we stopped to watch some boys playing football in a yard. They were being overseen by a group of besuited men on the steps of a nearby community centre. The boys and their fathers were from several Francophone African countries, the Ivory Coast, Congo, Guinea. Noticing my son’s interest, they asked if he wanted to join the game. As the football was kicked back and forth, I heard my son speak French, not just once, but several times over.

For a few days afterwards, my children’s interest in Africa was high. We went online to look at images of Benin, Burkina Faso, Congo (both the Republic of, and the Democratic Republic of), Madagascar, Mali, Senegal, Togo, Gabon, just a few of the many Francophone countries across Africa. I felt a new perspective opening up in front of my children’s eyes for the first time – one that revealed endless possibilities of communication and the discovery of otherness. Thanks to the language I was speaking to them, they had glimpsed a potential route into the immensity and wider heterogeneity of the world.

This inestimable heterogeneity is being threatened by the whirlwinds of globalisation and the tensions of the world. The death of languages is symptomatic of the myriad of crises the planet is engaged in, environmental, cultural and economic. A lost word means a felled tree; a vanishing language, another newly barren landscape. Vital roots to the past, tendrils towards the future, are being severed.

In the Bible, the toppling of the Tower of Babel was said to have set humanity on a path of mutual misunderstanding and confusion. Yet it seems unlikely that Globish-cum-English-lite will recreate harmony. The history of civil wars in monolingual countries certainly suggests otherwise. And at a time when difference is being assaulted from all sides, and the numbers of students learning a foreign language are dropping in many Anglophone countries, my wish to speak to my children in another language is a way of saying that the plurality and diversity of the world matters.