With her curling blonde hair and her slender limbs and her beautiful clothes, Inez was alluring in an obvious way, and yet it was easy enough to see that her slightly protruding blue eyes were blank screens of self-love on which a small selection of fake emotions was allowed to flicker. She made rather haphazard impersonations of someone who has relationships with others. Based on the gossip of her courtiers, a diet of Hollywood movies and the projection of her own cunning calculations, these guesses might be sentimental or nasty, but were always vulgar and melodramatic. Since she hadn’t the least interest in the answer, she was inclined to ask: ‘How are you?’ with great gravity, at least half a dozen times. She was often exhausted by the thought of how generous she was, whereas the exhaustion really stemmed from the strain of not giving away anything at all.

This amusing passage, written by Edward St Aubyn in his novel At Last (2012), touches upon Inez’s looks, social class, psychology and behaviours. It’s hard to imagine a better description, and it’s certainly superior to what people provide to each other conversationally or on dating websites. And yet, any particular reader will project his or her own stored images, memories and worldview upon Inez. She is different in each person’s mind. She is also a symbol of the worst traits of her social milieu – satire posing as personality.

Though normally with less flair than St Aubyn, we’re constantly describing ourselves and others. Sometimes, the stakes are low, as with idle chat, and sometimes they are higher, such as when we’re summing up a potential job candidate or a possible love match for a friend. Writers search for emotional granularity, consequential details and apt metaphors, while sociologists and personality psychologists have come up with sorting tools such as the ‘Big Five’ personality traits – extraversion, neuroticism, agreeableness, openness to experience, and conscientiousness. But if I tell you someone is ‘a nice-looking middle-aged Asian extravert who is fairly agreeable, neurotic and open-minded, and from the Midwest’ you have no idea what she’s really like. You barely have a starting point.

People have habits of speech, mannerisms, a temperament that is at least in part inborn, and even behavioural signatures and routines. But across time and contexts, any of these characteristics can change. We can act against our own proclivities until they aren’t proclivities anymore. Being enclosed in solid, distinct bodies fuels the belief that our personalities must be fully formed and consistent as well. But they aren’t. Everyone from pop-psych authors to business-school professors to astrologers has come up with her own system for sizing up people. If it were possible, wouldn’t one method have prevailed by now? In fact, two recent paradigm-breaking studies suggest that personality traits can shift slowly yet drastically over time, and quite quickly after therapeutic interventions.

A million tiny human factors – tone of voice, brand of shoes, frequency of smiles – form a gestalt as difficult to pick apart as it is to pin down. If a person contains multitudes and is perhaps even infinite, how can we compare infinities? This is a legitimate question for theoretical mathematicians, but in the science of personality (unlike mathematics) perception trumps precision most of the time.

This fluid state of affairs is often captured best by writers, who tend to have an agenda when delineating characters. What we’re often not conscious of are our own agendas when casually describing others. Do we want our audience to like the person we’re talking about? To see themselves in her? To – I don’t know – maybe draw a comparison that’s favourable to us? Just as people around us are in flux, so, too, are our intentions. Acting as though other people have personalities is sometimes a prerequisite to reaching our own social goals.

The messy mosaic of feelings and impressions that assemble in our own minds when we meet another person is brilliantly depicted in Mary Gaitskill’s novel The Mare (2015), about Velvet, a Brooklyn girl who grows close to Ginger, a middle-aged woman from upstate, and the horses stabled near her house. Here Ginger assesses Velvet’s mother, Alicia:

It took me a minute to realise that the power in her body didn’t come from her musculature or size, but from her character; she sat in her body like it was a tank.

Later Ginger meets a horse trainer named Beverly:

Her eyes were simple mentally but emotionally snarled, aggressive and shrewd like an orangutan’s. She looked out of her eyes so hard you couldn’t look into them. She was verbally polite to me while her face dismissed me with the fast scorn of a teenager. She looked like the kind of person who could really mess up a child.

These evocative outward descriptions are portals to interiors – but mostly to Ginger’s. Though she might think of them as personality descriptions, these are really her gut-level intuitions, which mingle with her own state of mind and shape how people appear to her. Ginger’s acute sensitivity to danger surfaces in the way she sees both these women. How the women act over time will tell us if her hunches are correct. Novelists know that behaviour is always more revelatory than a grocery list of traits.

Acknowledging the inadequacy of personality profiles devoid of context, writers often expose not the ‘truth’ about someone, but rather the gaping distance between how they see themselves and how others view them. To great comic effect, St Aubyn shows us just how ‘off’ Inez’s self-conception is. It’s a way in which the novelist has an advantage over the layperson: shrewd observers can mine for discrepancies between how someone presents herself and how she acts and talks, but the omniscient novelist need not piece together such a puzzle: he made her, he knows her. Similarly, defining someone against the stereotypes attached to them corrects the image conjured upon hearing that he is, for example, ‘a young working-class guy from Texas’. Such contrasts show how ludicrous it is to assume that someone’s personality will look the same in all lights. Our boastful, gun-toting Texan scores much lower on courageousness when sitting next to an actual war hero.

In the opening scene of Adelle Waldman’s novel The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P. (2013), Nate goes to his ex-girlfriend Elisa’s apartment for a dinner party:

Each time Nate saw her, Elisa’s beauty struck him anew, as if in the interval the memory of what she actually looked like had been distorted by the tortured emotions she elicited since they’d broken up: in his mind, she took on the dimensions of an abject creature. What a shock when she opened the door, bursting with vibrant, almost aggressive good health.

A few minutes later, though, after Elisa uses a whiny voice, Nate is reminded of her spoiled, ill-tempered quality:

Her prettiness became an irritant, a Calypso-like lure to entrap him, again. Besides, as he poked at his chicken with his fork, Nate noticed the pores on Elisa’s nose and a bit of acne atop her forehead, near her hairline, flaws so minor that it would be ungentlemanly to notice them on most women. But on Elisa, whose prettiness seemed to demand that she be judged on some Olympian scale of perfect beauty, these imperfections seemed, irrationally, like failures of will or judgment on her part.

Elisa’s morphing looks underscore not only the connection between character and appearance, but the fluidity of both. Romantic entanglements filter how we are perceived and how we act. Watching just how someone changes in the presence of various people provides interesting information. If you don’t see someone interact with others much, you can really only describe ‘him-with-you’, not so much ‘him’.

Novelists advance the plot and unroll their ideas as they describe characters, and Waldman’s passage above tells the reader just how observant and self-aware Nate is (he knows his critique of Elisa’s flaws is petty and irrational, but has a nuanced and sophisticated explanation for why it came to his mind). That’s why, later in the book, when Nate acts without self-awareness, it’s all the more frustrating for the women he casually mistreats. Blind spots are telling, and everyone has them.

It’s only natural to want to know which Game of Thrones character you are

The desire to guess how people will act and treat us, and to decode our own, sometimes irrational, behaviours, is what makes us desperately want to assign fixed personalities despite all the evidence of fluidity. We want to find our slot, once and for all, and to put everyone else in the right box, as though we were putting dolls in their designated beds in the dollhouse. There! Now we can rest easy.

A glut of pop-psych and business self-help books offer quizzes and tailored scripts for describing ourselves and others. Companies still use personality tests that have been proven to NOT predict performance. Yes, it’s a racket that exploits our desire to control a chaotic social universe, but while not definitive, these frameworks can uncover patterns of behaviour and thinking in ourselves and the people we care about. And they’re fun. It’s only natural to want to know which Game of Thrones character you are.

Analysing other people and ourselves is an often-entertaining pastime, sometimes cruel and mostly light-hearted. But gossip evolved as a complex survival mechanism. Personality parsing is a major component of dishing, but its deeper purpose is not to set others in stone – rather it is to decipher the ever-shifting norms and power dynamics of our main group. What we’re really doing when we describe people is bonding with others, forming alliances, and gauging how our own potential actions will be perceived. We’re all running test-cases by each other featuring mutual friends and acquaintances or high-status luminaries and celebrities. If we collectively decide to acknowledge the fluid personality, we will overcomplicate the crucial business of gossiping.

As for the hard data (such as it is within the social sciences), roughly 50 years of organising adjectives have led to the dominant model in personality psychology, where you can be rated low, middle or high on any of the aforementioned ‘Big Five’, and further categorised into subtypes, such as ‘lively’ or ‘risk-averse’. The problem with applying this system is that where people sit on these scales does not seem fixed and usually isn’t at the extremes, by definition. Tendencies, while real, are not as revealing as countertrends: a friend is an extravert, except when she’s with her colleagues. A daughter is agreeable at school, but pretty cranky at home.

While many psychologists have long held the view that personality is formed in childhood and remains stable, a few new studies have challenged that tenet as well. In a meta-analysis published this January in the journal Psychological Bulletin, a team of researchers found that neuroticism tends to decrease as people age. More surprisingly, they found that just a few months of therapy can lower neuroticism substantially – to about half of what 40 years of living would do to a neurotic person. Another study, published in Psychology and Aging, is the first to compare personality measures of the same people, as teenagers and 63 years later. Though the measurements don’t line up exactly with the Big Five, scores at 14 had no correlation with scores at 77.

Other studies show that cities and regions have personality traits (yes, California is laid-back). What this tells us about residents could be twofold: either their environment is having an effect on them, or they have chosen an environment with an established personality profile to fit who they already are.

A person’s friends and family members are continually shaping them too. Just look at the well-documented ‘social contagion’ effect, in which our habits, values and moods are influenced by those we hang around. We can’t make the tempting mistake of seeing people as independent actors moving through space, untouched by their settings and connections.

If we want to describe someone, we need to know what her core pursuits are at any given time

One theory of personality seemingly contains the various truths that personality scientists have uncovered so far, by allowing for the impact of context and life phases on character. Brian Little, a psychologist at the University of Cambridge, lays out three aspects of personality in his book Me, Myself, and Us (2014). The first is ‘biogenic’, and includes the neurophysiological qualities largely determined by genes. The second is ‘sociogenic’, and covers the cultural and social influences on how people act and think. The third is ‘idiogenic’, with a focus on the traits that make someone unique.

What Little calls ‘personal projects’ refers to whatever goals, dreams or pressing situations a person is dealing with at any given time. ‘Free traits’ are those that go against our biogenic personality, but that are in service of these projects. The agreeable person could become demanding when advocating for the health of a spouse, for example. It follows that, if we want to describe someone, we need to know what her core pursuits are at any given time. She might be acting ‘out of character’ to achieve a goal, rather than exhibiting a longstanding attitude or approach.

A master essayist who is also a renowned psychotherapist could be expected to hold a balanced view of the construct of personality and its limitations. But Adam Phillips, in an interview with The Paris Review in 2014, blows up the entire premise:

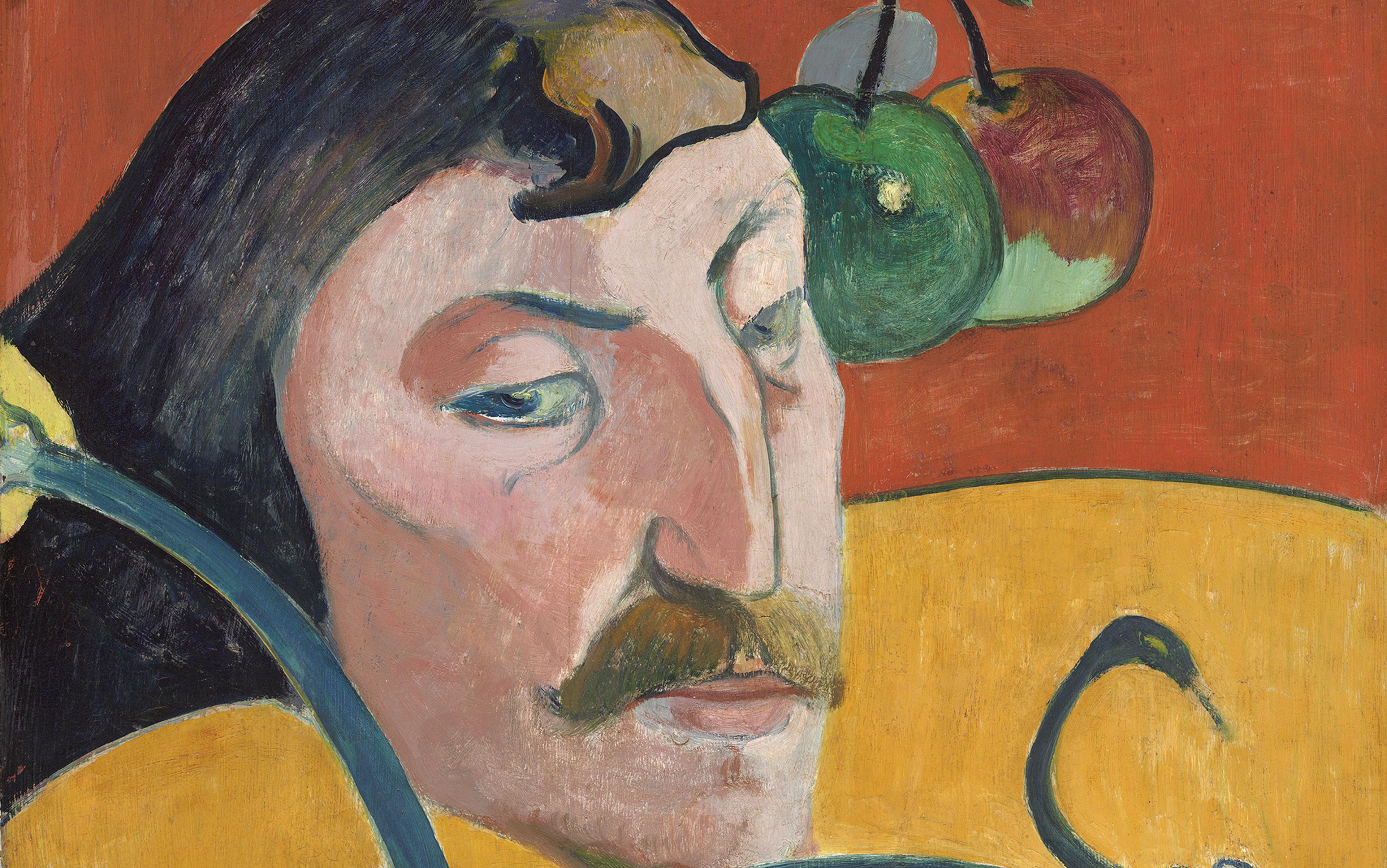

When people say: ‘I’m the kind of person who,’ my heart always sinks. These are formulas, we’ve all got about 10 formulas about who we are, what we like, the kind of people we like, all that stuff. The disparity between these phrases and how one experiences oneself minute by minute is ludicrous. It’s like the caption under a painting. You think, well, yeah, I can see it’s called that. But you need to look at the picture.

Psychoanalysis, Phillips says, should show us how much our wish to know ourselves and others comes from anxiety, and that it’s ‘possible to live as yourself not knowing much about what’s going on’.

While we’ll never stop trying to figure others out, Phillips’s comments are a poignant reminder that when we describe a child as ‘defiant’, or a friend as ‘needy’, or an acquaintance as ‘easy-going’, we’re heading off opportunities for them to grow, to change, to be walking contradictions, to be amorphous, to improvise. Embracing the fluid personality accommodates other people more generously and convinces us that we, too, can change if we want.