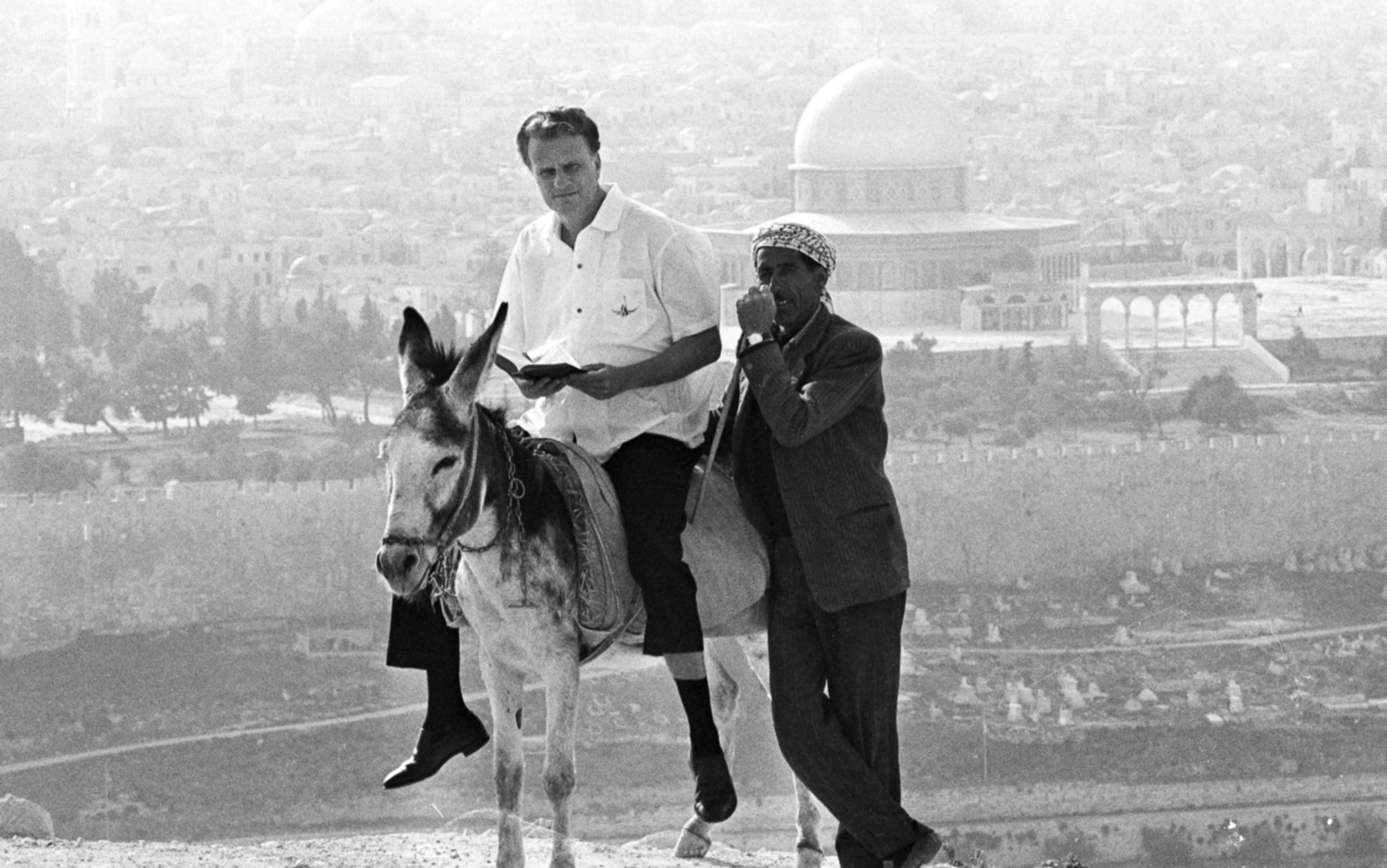

On 23 June 1969, at the Midtown Manhattan headquarters of the American Jewish Committee, the evangelist Billy Graham met with two dozen rabbis and Jewish leaders. According to one rabbi, the meeting was to allow Graham to convey ‘the need for dialogue and communication’ between American evangelicals and American Jews, and to find common ground by explaining ‘his relationship with Israel’. It was a pivotal moment in the American Jewish and evangelical Protestant interfaith relationship.

Though some of the Jewish leaders were wary of the ‘wild raving fundamentalist’, Graham won them over. He cited the Hebrew Scriptures, or Old Testament, to describe his understanding of God’s covenant with the Jewish people, and explained his support for Israel as recompense for past Christian anti-Judaism. ‘All Christians are guilty as far as Jewish experience was concerned,’ he said. Graham also spoke of his conversations with the Israeli prime minister Golda Meir, and assured American Jewish leaders that the United States’ president Richard Nixon was ‘extremely sympathetic’ to Israel.

Today, for many evangelicals, Christian Zionism is no mere side issue. They believe that they are not only correcting the ancient injustice of anti-Semitism, but contributing to the salvation of the world and the completion of God’s redemptive plans. It is, for many, the metanarrative that makes sense of the biblical drama and current events, and provides a road map for the future.

That 1969 meeting contained all the essential elements characterising the exceptional support that evangelical Protestants in the US give to the state of Israel. The spirit of this meeting has since been replicated dozens of times. Graham weaved an evangelical reading of the Bible, a deep-seated longing to aid Israel, and the self-interested power calculations of both communities into a language of interfaith rapprochement and shared Jewish-Christian interests. His Jewish colleagues, concerned about the future of Israel, and cognisant of the evangelicals’ influence, were eager to create new lines of cooperation.

Pressed on theology, Graham would have affirmed his commitment to the exclusive truth claims of Christianity, while the American Jewish leaders undoubtedly retained their own theological exclusivity. Still, their peculiar set of shared interests led to a powerful and lasting partnership. Their alliance is one of the most notable instances of interfaith cooperation in recent history.

In the wake of Europe’s religious wars, exclusive claims to religious truth – ‘theological intolerance’, as Jean-Jacques Rousseau called them in The Social Contract (1762) – grew to be seen as an impediment to civil relations. ‘It is impossible to live at peace with those we regard as damned,’ wrote Rousseau, ‘to love them would be to hate God who punishes them: we positively must either reclaim or torment them.’ But the alliance of American evangelicals and American Jews proves that Rousseau’s dictum is not necessarily true.

Close to 50 years after that meeting, evangelicals and Jews remain at loggerheads on most theological and cultural issues. In the face of these vast differences, they have managed to unite – in ever closer cooperation – over support for Israel. No individual has inherited Graham’s stature atop American evangelicalism, and his multiple successors do not share uniform attitudes toward Israel. But many of them lead influential Christian Zionist organisations that constitute one of the most successful single-issue movements in modern US politics.

Christian Zionists have achieved exceptional unity and influence on support for Israel, using a sophisticated combination of religious, historical and political components. They emphasise a potent type of interfaith engagement that elevates biblical covenantal language, and offer a sanitised version of the Jewish-Christian past, yet also orient their work toward the pragmatic goal of increasing political influence.

Interfaith cooperation is a liberal ideal: the world can be a better place if different religions work together

Understanding Christian Zionism as an important instance of interfaith cooperation helps us understand the powerful ways in which it has shaped not only relationships between Jews and Christians but the identity of American evangelicals.

Interfaith cooperation is at least as old as Moses’ flight to Midian, when he took refuge from his Egyptian pursuers with Jethro, a priest of an unknown religion, who became his father-in-law. Yet the mere fact of people of different religions working together is not the essence of interfaith cooperation. The term is a modern one, and its meaning is found in the 20th century.

Liberal ideas of interfaith cooperation lionise progressive values, expand tolerance, and help to build more democratic civil societies. And interfaith cooperation is a liberal ideal. From the British writer Karen Armstrong to the American campaigner Eboo Patel, its proponents claim that individuals and communities of different religious backgrounds will make the world a better place if they cooperate and work together.

Nonprofits such as Patel’s Interfaith Youth Core in Chicago and the World Faiths Development Dialogue in Washington, DC offer many historical examples of interfaith cooperation, and they’re always progressive. These include the civil rights partnership between Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr and Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, and the collaboration between Mohandas Gandhi and Bacha Khan in the movement for Indian independence. Sometimes, proponents reach back further, to the cooperative culture of Al-Andalus in medieval Spain and the enlightened reign of Akbar the Great of the Mughal Empire. These examples stand for more peaceful cohabitation, more equality, more happiness, more justice, and more civilisation.

But Christian Zionism rejects progressive ideals and embraces a very different understanding of the world. That’s why it’s seen – by mostly liberal social scientists and journalists – not as a pioneer in interfaith cooperation but as an apocalyptic movement, a Right-wing political grouping, or even a neocolonial venture. To be sure, these analyses offer useful insights, but as a movement of Christians seeking cooperation with Jews, Christian Zionism also represents one of recent history’s most important interfaith cases.

Christian Zionists are seeking to enact what they consider the values of Jewish-Christian cooperation in political and religious terms. Starting with a specific political issue – the wellbeing of Israel – Christian Zionism structures the interfaith relationship in its service. The movement is built to make the case that this goal is vital to evangelical Christians and their identity.

Christian Zionism projects a specific vision of God’s covenantal guarantees and their eschatological fulfilment. In short, it makes God’s promises and their scope more certain, more selective, more exclusive in understanding God’s dealings with humanity. This specificity sets Christian Zionism apart from other interfaith movements, and goes far in explaining its affinity to a certain understanding of Jewish identity.

The issue in which this specificity pays interfaith dividends is in securing Jewish possession of Israel’s covenanted land. The ‘land’ consists of the sites of biblical history and the biblically mandated borders that God in Genesis grants to Israel’s patriarchs. For Christian Zionists, these make up the ideal borders of the state of Israel and include the contested West Bank.

It’s key that US evangelicals’ political Zionism took shape after the Arab-Israeli War of June 1967. This timing meant that, post-1967, evangelical understandings of Israel became preoccupied with its sovereignty over the covenanted land. In the wake of that war, which saw Israel take control of the West Bank, Gaza Strip and East Jerusalem, Jews themselves were undecided on Israel’s significance. The trend, more obvious and expected in Israel, was to emphasise the centrality of land to Jewish identity. The entirety of Judaism could be distilled, in the words of the Israeli official Yona Malachy, to ‘the tripartite union of religion-people-land’. ‘The recognition of the tie between the Jewish people and their country must become the central theme of any future dialogue between Christianity and Jewry,’ he warned in 1969.

Among American Jews, there was less consensus on the preeminence of land to the meaning of Israel, though certainly many came to see the success of Israel as core to their own identity. One of the leading US conservative rabbis, Arthur Hertzberg, claimed in 1971 that ‘the state of Israel … is necessary for the continuity of Judaism and Jews’. Rabbi Marc Tanenbaum, the American Jewish Committee’s director of interreligious affairs and an organiser of Graham’s 1969 meeting, insisted that ‘Christians face and accept the profound historical, religious, cultural and liturgical meaning of the land of Israel and of Jerusalem to the Jewish people’.

American Protestant evangelicals found these demands compelling, mostly for reasons related to their own ideas about the ‘end times’ and Christ’s second coming. For some evangelicals, Israel represented ‘God’s timepiece’ and the centre of the fulfilment of biblical prophecy. For others, it was a testament to God’s fidelity to his chosen people. Many of these eschatological interests also emphasised the central role of Israel in the end times.

Each step that Christian Zionists take toward Jews in practice means a step away from Muslims

Post-1967, Christian Zionists adopted the emerging Jewish emphasis on Israel as their own. For the US evangelical educator and activist G Douglas Young, the tragedy was that ‘Christians in the US did not, nor do they, understand the Jews’ self-understanding of themselves and their interest in the land of Israel’. Young headed an evangelical graduate school in Jerusalem dedicated to the mission of helping students ‘com[e] to grips with the problem of the Jew’s self-evaluation and his interest in the land’. His selectivity of who defined the Jewish interpretation of Israel (largely Israeli Zionists) should not detract from his explicitly interfaith understanding of his mission.

Other evangelicals soon followed. Along with Graham, the presidents of the National Association of Evangelicals and the Southern Baptist Convention in the late-1960s indicated an openness to adopting what they called a ‘Jewish self-understanding’ of Israel. It was basically a ceding of what Israel meant and should mean in the world today, while holding fast to an eschatology that forecast a bad ending for all non-Christians, including the vast majority of Jews.

After 1967, from the narrow starting point of overlapping concern for the security of Israel, Christian Zionists and their Jewish partners developed a shared set of values. Christian Zionists soon extended their thinking to related issues of anti-Semitism, religious persecution and secularism. Today, they are the most active partisans for Israel on US university campuses. They oppose the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement, and lobby governments around the world to favour Israel.

A shared fixation on those deemed Israel’s enemies has been integral to this worldview. Arab Palestinians (both Christian and Muslim) hardly receive a hearing by Christian Zionists – a justification often voiced on grounds of interfaith solidarity with Israel. Each step that Christian Zionists take toward Jews, however, in practice means a step away from Muslims. The promise of an ‘Abrahamic’ dialogue or a tri-faith cooperative is nowhere dimmer than in Christian Zionism. In the name of interfaith cooperation, Christian Zionists find theological justifications for most Israeli policies.

Regardless of these political choices, Christian Zionists understand their support for Israel as participation in the redeeming work of God. At the dawn of US evangelical organisation for Israel, Young called for action as a necessary extension of Christian faith. ‘Are you helping the new nation of Israel?’ he asked in The Bride and the Wife (1960). ‘Are you helping them in material and physical ways? Are you expressing real friendship always?’ Assuming the burden of Israel’s security, Young argued, was a Christian duty and a tangible expression of interfaith solidarity between God’s two chosen peoples, the Church and Israel.

The influence of Zionism also led to recasting interfaith cooperation with Jews as a realisation, rather than a deviation, of evangelical identity. This is evident in the area of evangelical missions to the Jews – long the most contentious barrier to any type of Jewish-Christian rapprochement. Largely as a result of Christian Zionist activism, evangelical leaders – from John Hagee, the founder of Christians United for Israel (the largest Christian Zionist organisation in the US) to the European leadership of the International Christian Embassy Jerusalem (the largest Christian Zionist organisation in the world) – have disavowed missions.

Hagee’s book In Defense of Israel (2007) sought to curb the evangelical obligation of Jewish missions by claiming that Jesus never really meant to save the Jews. ‘The Jews did not reject Jesus as Messiah; it was Jesus who rejected the Jewish desire for him to be their Messiah,’ he wrote, seemingly opening the way for Jews to be saved through their own covenant with God. Outcry by fellow evangelicals led Hagee to revise this specific language, but not his organisation’s refrain from missions.

Rather than endorse missions, Hagee and other Christian Zionists recast support for Israel as necessary Christian penance for the Church’s past mistreatment of Jews. The guilt felt by Christian Zionists is often palpable. ‘Anti-Semitism,’ Hagee wrote, ‘has its origin and its complete root structure in Christianity, dating from the early days of the Christian Church.’ This language is an echo of post-Holocaust Christian theologians – including Father Edward Flannery, whose book The Anguish of the Jews (1965) Hagee cites as formative to his understanding of Jewish-Christian history.

Support for Israel is just one side of the recent evangelical revaluation of Judaism. Once maligned as the religion of ‘Christ-killers’ and ‘Pharisees’, Judaism is now seen by evangelicals in a better light. The reasons for the change include a decline, following the Holocaust, in anti-Semitic views among all Americans, the pluralism of postwar ‘Judeo-Christian’ civil religion, and, less well-known, a revolution in biblical studies and related fields that emphasise ‘Hebraic’ over ‘Hellenistic’ influences on the Bible. Yet it was not principled commitment to pluralism that raised the change in evangelical views of Jews and Judaism, but rather a confluence of politicised eschatology with new intellectual authority urging closer Jewish-Christian cooperation.

Even outside the Christian Zionist movement, evangelical scholars of early Christianity and Judaism have changed their understanding of Jewish-Christian relations. In evangelical colleges and seminaries across the US, instead of Judaism as the negative mirror image of Christianity (the ‘law’ to Christianity’s ‘grace’; the ‘particularism’ to Christianity’s ‘universalism’), scholars now emphasise the Jewish heritage of Christianity and the mutually reinforcing values of the two traditions.

They managed to link academic insights and political organising as two sides of evangelical identity

In the past couple of generations, many evangelical scholars propelling this trend have studied at Jewish institutions: Marvin Wilson, whose book Our Father Abraham: Jewish Roots of Christian Faith (1989) earned a PhD from Brandeis University in Massachusetts, which is sponsored by the Jewish community; the aforementioned Young, founder of Bridges for Peace, the oldest Christian Zionist organisation, earned a PhD from what was then Dropsie College in Pennsylvania and is now the Herbert D Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies. A later generation of evangelical scholars studied at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, including Brad Young (no relation to G Douglas Young), now a professor of Judaic-Christian studies at Oral Roberts University in Oklahoma who recently graduated his first Orthodox Israeli student in the same field. These scholars have, to varying degrees, personally supported Christian Zionist causes, all arguing that partnering with Jews on Israel is a moral and theological good.

Jewish voices have encouraged this change of attitude. David Brog, the director of Christians United for Israel, calls Jews and evangelicals ‘blood brothers’. Rabbi Shlomo Riskin, a founder of the West Bank settlement of Efrat, heads the Center for Jewish-Christian Cooperation and Understanding, organising joint Jewish-evangelical prayer groups, Bible reading groups and pro-Israel rallies.

The constituent parts of Christian Zionist thinking arise from this milieu of shifting and interacting evangelical and Jewish thought. Less acknowledged but no less important, other Christian work has also informed the transformation of evangelical attitudes. The pioneering scholarship of E P Sanders on Paul’s Hebrew background, the biblical archaeology of William Foxwell Albright, the New Testament research of the Israeli scholar David Flusser provided the foundations for the remarkable Jewish-Christian dialogues that have emerged across North America and Europe, from the Catholic Church’s Nostra Aetate declaration of 1965 to the World Council of Churches’ denunciations of anti-Semitism.

Unlike most interfaith encounters in the 20th century, Christian Zionists managed to bundle these insights and claims with an argument that cooperation was meaningful only if realised through political action. They managed, in essence, to link academic insights and political organising as two sides of evangelical identity. Few if any activists or special-interest groups have more effectively brought scholarship and political action into concert.

Like most American Jews, Israeli Jews differ with American evangelicals on a host of religious, cultural and political issues, from the economy to abortion to women in combat service. The cultural differences between evangelicals and Israelis are vast. Yet Christian Zionism shows that shared values need not be the basis of interfaith cooperation. The evangelical-Zionist bond has faced great challenges and has lasted by clinging to a very narrow set of shared interests. Yet the ideas underpinning Christian Zionism shape both evangelical identity and Israeli understandings of the US.

This is far from an endorsement of Christian Zionism. Criticisms of the movement’s politics, theology, tendency toward apocalypticism, ignoring and ignorance of the Palestinian experience and interests, anti-Muslim stereotyping, and near-unquestioning allegiance to Israel are all worthy of discussion. But Christian Zionism should not be misrepresented. A fundamentally interfaith alliance has informed and propelled Christian Zionists into the very halls of power. They have succeeded, in a way few interfaith movements have.