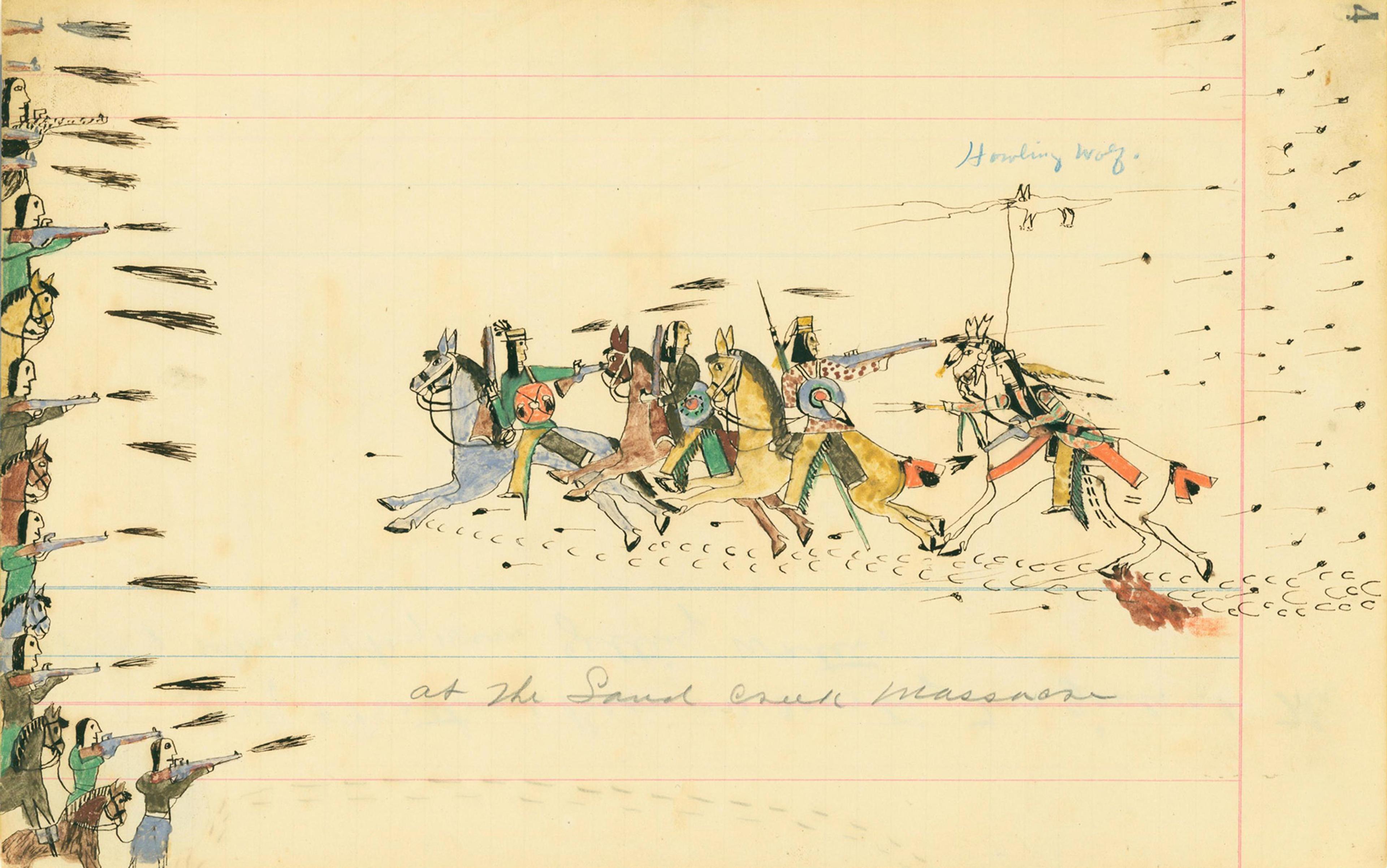

On the morning of 29 November 1864, nearly 700 United States soldiers charged towards a village along a gentle bend at Sand Creek, in Colorado Territory. Settled in peace for the winter, there were dozens of Cheyenne and Arapaho families there. Within hours, the soldiers killed more than 200 Cheyenne and Arapaho – mostly women, children and the elderly. Over the next day, the soldiers pillaged the dead for trophies – including ears, fingers, genitalia and scalps. These body parts were taken to Denver, where soldiers paraded them in the streets and displayed them in homes. Most of the pilfered human remains were lost to time. A handful would survive as artefacts in museums and private collections.

The Sand Creek Massacre took place more than 150 years ago. Yet, it has not yet ended. This crime of American expansionism has continued to reverberate through the generations. The original war over land and dominance has transformed into a battle over memory and emancipation. The demand for the return of ancestral human remains from museums is perhaps the most visible – and tangible – struggle for Native America’s cultural survival. Repatriation asks us to consider whether we can ever fully come to terms with the past.

In 2008, descendants of the Cheyenne and Arapaho victims gathered at the newly established Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site in southeastern Colorado. At a specially designated area not far from Sand Creek, religious leaders buried the remains of six victims – one scalp from the Denver Museum of Nature & Science, one scalp from the Colorado Historical Society (now History Colorado), a cranial fragment from the University of Nebraska, and three sets of remains from a private collection.

‘A Cheyenne elder told us our nations couldn’t heal and couldn’t regain our strength and we as individuals couldn’t heal,’ Suzan Shown Harjo, a leader of the repatriation movement of Cheyenne and Muskogee descent, once said, ‘until we recovered our dead relatives from these places.’

But did the return of the victims’ remains quiet the phantoms of the past? Can repatriation heal the wounds of history?

‘Repatriation’ is derived from the Latin repatriatum, meaning something that has gone home again. In the past several decades, repatriation has become a global controversy as communities and nations struggle to reclaim their stolen heritage from museums and private collections. In the US, hundreds of Native American tribes have negotiated with some 1,000 museums and agencies over the future of more than 200,000 Native American skeletons, and 1 million grave goods and sacred objects.

As early as 1620, shortly after the Pilgrims landed in New England, they dug into an Indian grave, stealing ‘sundry of the prettiest things’. In the centuries that followed, European immigrants often saw Native American cultural objects as trophies for the taking, little different from land, water, timber or other resources. By 1906 in the US, law allowed archaeologists and curators to assume the role of the stewards of Native American material culture. This work has reaped great benefits for science and the public but involved steep costs – for Native communities. The pillaging of graves for someone else’s education and entertainment violated Native America’s humanity and dignity. Across the generations, the collection of Native Americans’ sacred objects and human remains by Euro-American institutions fostered a sense of powerlessness, hopelessness and anger among Native Americans. Naturally, this amassing of their material history appeared to Native peoples not as memorialising, but as a continuing form of domination and subjugation.

In 1990, this history was finally confronted when the then president George H W Bush signed the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) into law. NAGPRA created a process for museums and federal agencies to return cultural items to lineal descendants, Indian tribes, and Native Hawaiian organisations. So far, NAGPRA has resulted in the return of approximately 14,000 sacred and communally owned objects, 50,000 skeletons, and 1.4 million funerary objects.

Like in post-war Germany, descendants of Native American victims live among descendants of the perpetrators

A central theme of the NAGPRA law, and repatriation, is its healing effects. During the return ceremony of a totem pole in 2001, for example, a Tlingit tribal member explained: ‘These treasures coming back to Alaska are an important way of bringing unification and healing.’ Outside the US, in 2011, the Australian government declared: ‘Repatriation is also a vehicle for healing and justice in Australian society.’ Many feel that, as the museum curator and Tuscarora tribal member Richard Hill once wrote: ‘Repatriation must heal old wounds.’

Postcolonial psychology helps to explain how repatriation can heal. Russell Thornton, an anthropologist at the University of California, Los Angeles, and Cherokee, has written about the possibility of ‘traumas of history’ – past events that cause damage to an individual or community that must be resolved for psychological health. Drawing from research on Holocaust survivors, Thornton explains how Native Americans have difficulty mourning mass deaths. Like those who lived in post-war Germany, the descendants of Native American victims continue to live among the descendants of the perpetrators. Thornton argues that without resolution, historical traumas are ‘intergenerationally cumulative, thus compounding the mental health problems of succeeding generations’.

Thornton concludes that repatriation is needed for ‘closure’. When ‘tears are shed’, he writes, the pain of the past ‘can be eased’.

‘Can repatriation heal?’ I ask but Joe Big Medicine doesn’t answer my question. He just sips his steaming coffee, then draws a paper napkin across his sparse moustache. Joe’s eyes are masked behind sunglasses with large, dark lenses. Yesterday, Joe, a Southern Cheyenne religious leader who conducts reburials and is an advocate for remembering Sand Creek, told me that the time is right to share his story. But now I sense that he doesn’t know if he can trust me. I’m a museum curator, after all.

When I arrived at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science as a newly-hired curator in 2007, I learned that I was employed by an institution that had inherited a material memory of 1864. Long ago assigned the catalogue number AC.35B, in the museum collections was a scalp – a clump of long hair attached to a bit of leathery skin – taken by Corporal William B Jacobs at Sand Creek. I set out to study whether the burial of this scalp in 2008 has healed history’s wounds.

In a survey I conducted in 2010 of 115 tribal officials who oversee repatriations, 54 per cent agreed that repatriation can and does heal. What was especially notable was that healing was not described as one uniform process. For some, healing was an inner emotional state, a sense of satisfaction, honour or pride, and increasing feelings of respect, hope and forgiveness. Others described healing as a spiritual journey for both the living and the dead, which, when it ends, allows the ancestors to be ‘at rest’. Still for others, healing can follow only from justice. As Jimmy Arterberry of the Comanche Nation explained: ‘Repatriation is simply the opportunity to acknowledge that something wrong occurred, and that there is a potential right to that wrong. Healing to me is the acknowledgment of a wrong deed, followed by corrective action.’

‘The language used to discuss repatriation is exactly the language of Oprah Winfrey’

Yet, 15 per cent of survey respondents said repatriation does not heal, while 31 per cent were unsure. They explained that repatriation is an unending task, that healing cannot occur until all of their ancestors and sacred objects are returned from museums.

In his book Do Museums Still Need Objects? (2010), the historian Steven Conn’s critique of repatriation is far more cutting. He dismisses Thornton’s embrace of postcolonial psychology, arguing that the US Congress cannot mandate healing. ‘Therapy speaks to individual needs,’ Conn adds, ‘not to collective, achievable goals.’ Conn concludes that repatriation ‘participates in the whole culture of therapy and “self-help” that has become such a major preoccupation of many Americans. The language Thornton uses to discuss repatriation is exactly the language of Oprah Winfrey.’

When Joe Big Medicine finally answers my question, he at first seems equally skeptical about the law’s curative effects. ‘NAGPRA doesn’t heal,’ he simply said. After a pause, he added: ‘But the process does.’

Repatriation is not merely about the return of things. It is part of the larger effort to fill in the gaps of culture left in colonialism’s wake.

In 1986, when the US Congress contemplated a national repatriation law, it did not propose legislation that was retributive (punishing museums for past actions) or distributive (redistributing cultural objects in an equitable way, like a social good such as education or health care). Rather, Congress envisioned legislation that was geared towards a kind of restorative justice in which the history of disrespect would be replaced by respectful reburials and repatriations. The first drafted repatriation legislation was titled the ‘Bridge of Respect Act’.

In parallel with the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), NAGPRA is not a ‘victor’s justice’, but a form of reparation arrived at through compromise and concern for the future wellbeing of different communities. In both apartheid and museum-collecting, the problem was an institutionalised violence that turned an entire class of individuals into victims, while the perpetrators were spread so diffusely over time and among institutions that punishment would be difficult.

The TRC famously sought testimony from all those caught up in the web of apartheid. Unlike a court case, the goal was not to find suspects to punish or exonerate. Instead, it was to expose and illuminate. Although in practice uneven, the South African TRC sought a restorative justice that was profoundly concerned, as Desmond Tutu wrote in No Future Without Forgiveness (1999), with ‘the healing of breaches, the redressing of imbalances, the restoration of broken relationships. This kind of justice seeks to rehabilitate both the victim and the perpetrator.’

Repatriation clearly seeks to restore property and ancestors to their cultural places. But its work towards healing is far more about the process than the result. Repatriation is part of this process of coming to terms with the past – not to reprimand but to repair. In the end, repatriation is a collective project – and requires a collective therapy – because it is not a trauma of the individual. The return of stolen remains and artefacts addresses deep rifts that have divided tribes and museums for decades.

‘Once you learn about it, your heart doesn’t heal. I’ll always have that scar of what happened to our people’

Joe Big Medicine’s work on repatriation contributes to an expansive effort of the Cheyenne and Arapaho to regain control over their lives by reclaiming power over their past. The struggles have included establishing a memorial at Sand Creek; changing the mascot (the ‘Savages’ logo: a Native American man in a headdress) of the high school nearest to the massacre site; and hosting the annual Sand Creek Massacre Spiritual Healing Run, which starts at the massacre site and culminates 177 miles away in Denver at the steps of the State Capitol building.

As the Australian museum theorist Moira G Simpson has argued, repatriation is perceived as contributing to a broader notion of wellness when it is considered a cultural revitalisation movement. If colonialism strips culture from subjugated communities, then postcolonial healing must involve redrawing what has been erased. For many, healing is that act of remembering.

I later wondered if part of Joe Big Medicine’s hesitation to my question might have come from a tension inherent in the term ‘healing’, which is derived from the Old English hǣlan – meaning ‘whole’. To be healed is to be whole again. Yet for Native peoples, the wounds of history might never fully disappear. ‘I myself will never be healed,’ Karen Little Coyote, who now helps direct the Southern Cheyenne’s repatriation programme, once told me. ‘It’s like a close family member, one near and dear, who has died. Once you learn about it, and think about it, your heart doesn’t heal. I’ll always have that scar of what happened to our people.’

Yet scars are a particular form of healing. As a constant reminder of the original wound, they can provide a source of strength for Native Americans to endure. Scars are proof of survival.