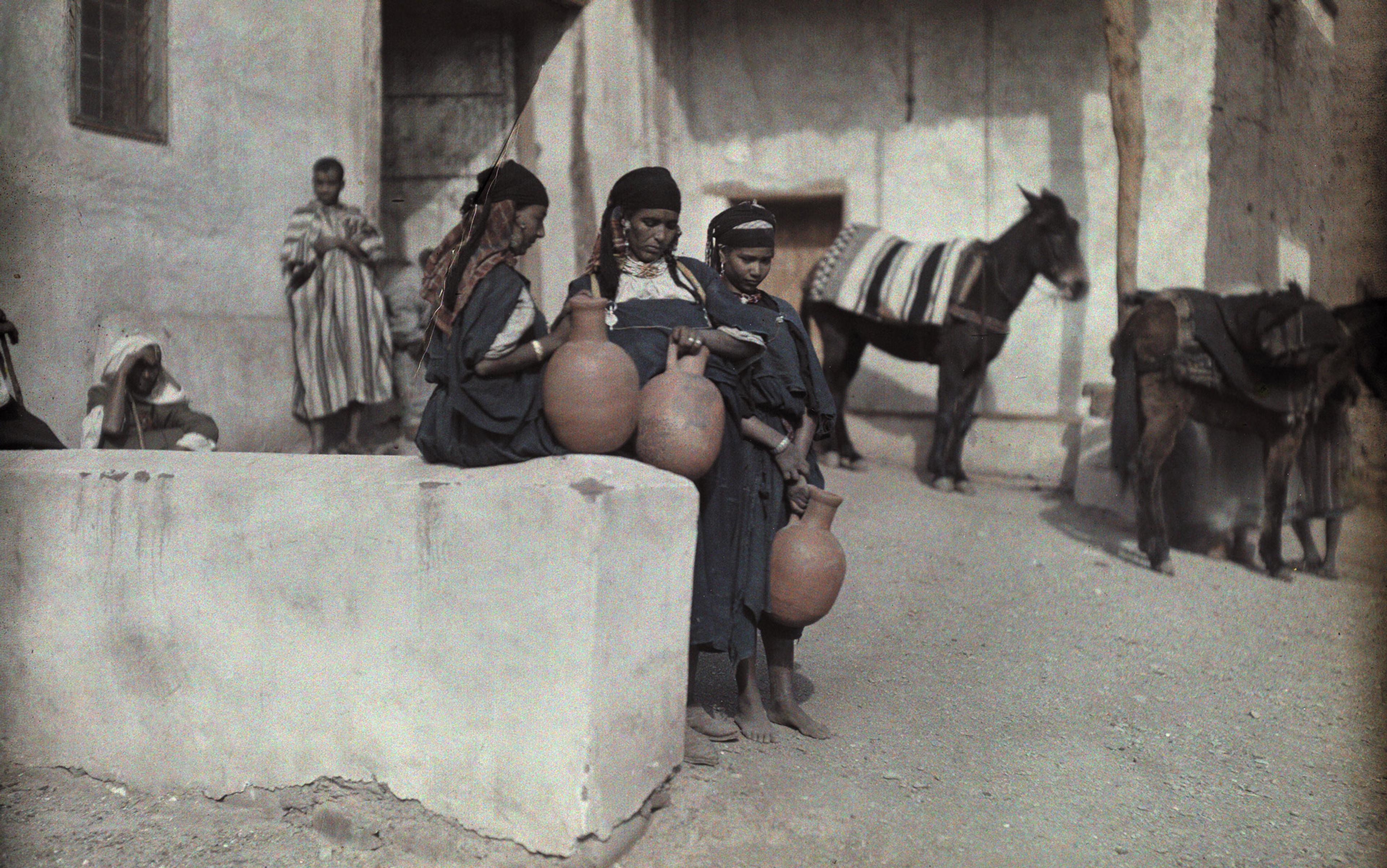

When you hear the words ‘Barbary pirate’, images of violence, slavery and alien culture probably come to mind. They might even conjure associations with jihad and crusade, wars between Christians and Muslims, and European battles with piratical enemies. It might be hard to imagine Europeans ever freely migrating to the region – unless it was to switch sides in search of wealth and glory. But these cultural associations, born in large part from 19th- and 20th-century colonial domination and European Orientalism, obscure a longer precolonial history of cooperation, exchange and evenly balanced, reciprocal conflict.

While the American troops in Dennis Malone Carter’s painting Decatur Boarding the Tripolitan Gunboat (1841) were at war with Tripoli in 1804, it was only because, following the American Revolution, they forfeited the protection of a century-old British-Tripolitan treaty.

Decatur Boarding the Tripolitan Gunboat (1841) by Dennis Malone Carter. A depiction of the events of 3 August 1804; the flag in the centre is a fanciful misinterpretation of one used by the Barbary pirates. Courtesy Wikimedia

As seen in Laureys A Castro’s painting A Sea Fight with Barbary Corsairs (c1681-86), the English ships were at war with Algiers, and had been, on and off, since 1664. But the Anglo-Algerian War of 1678-82 would be the last major military conflict between them for more than 130 years.

A Sea Fight with Barbary Corsairs (c1681-86) by Laureys A Castro. Courtesy the Dulwich Picture Gallery, London

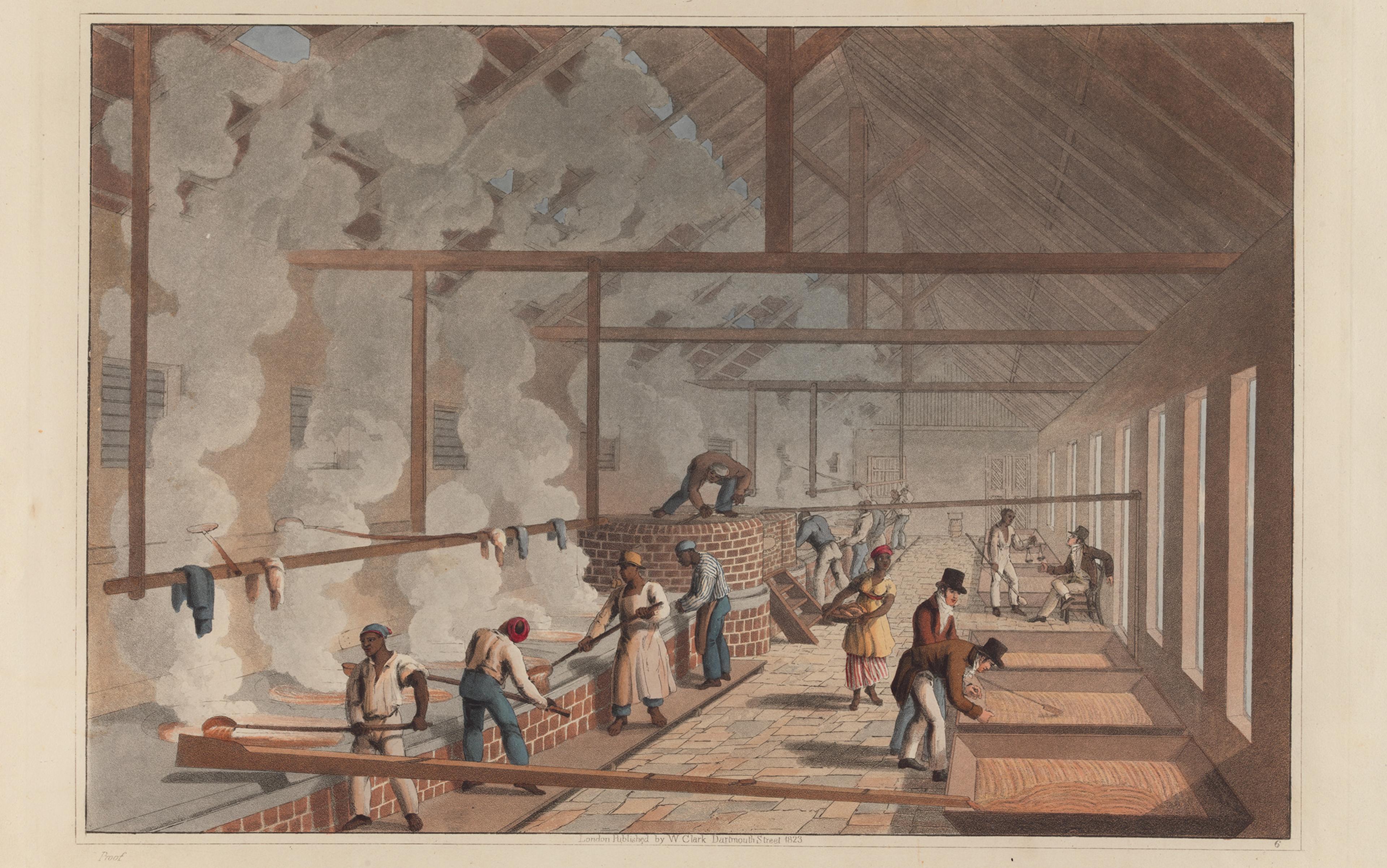

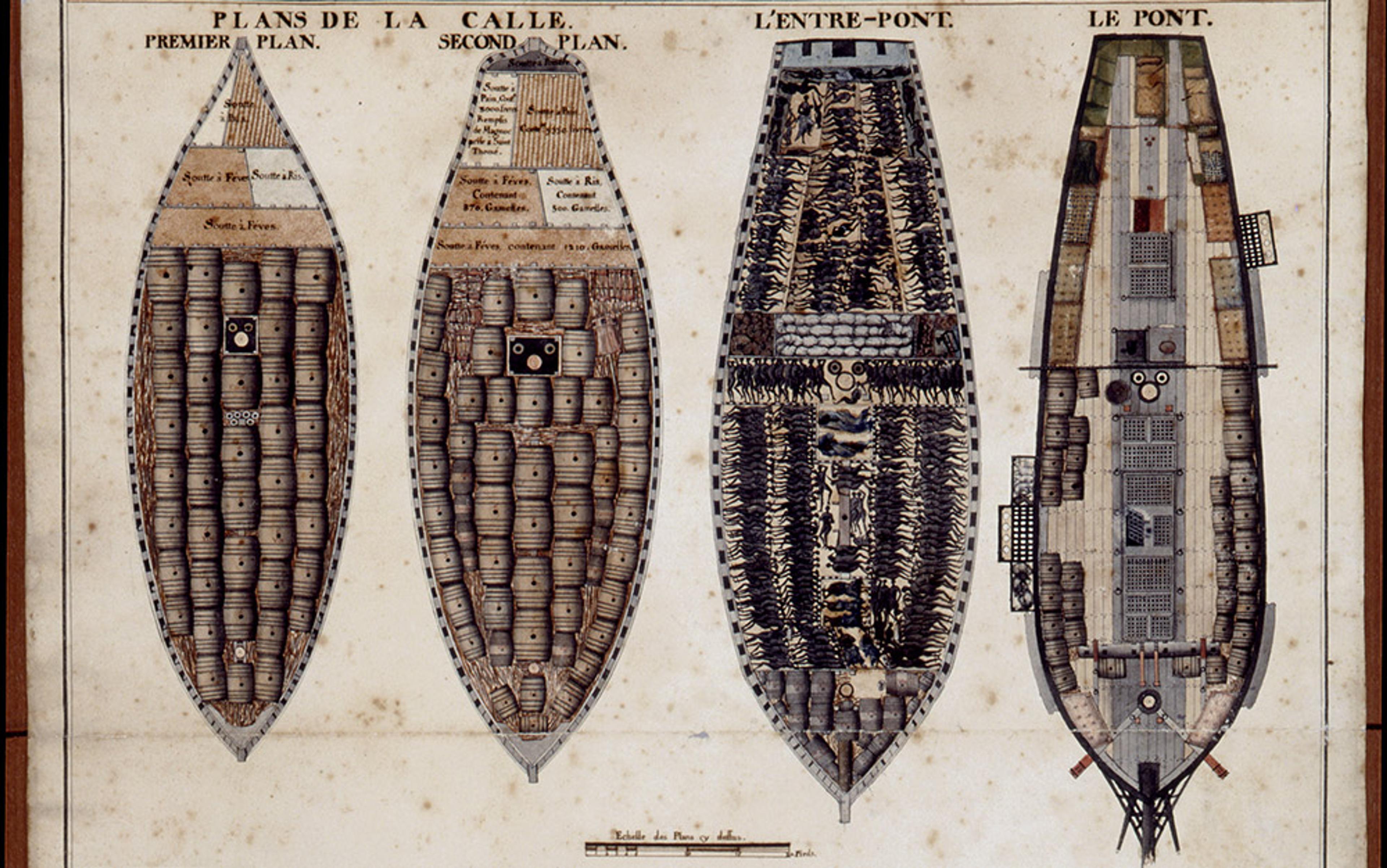

During the 16th and 17th centuries, both European Christians and Maghrebi Muslims were capturing, enslaving and selling their enemies all around the Mediterranean. Though they sometimes invoked holy war, economy and politics regularly took precedence, and Muslim captives were particularly prized for their purported endurance on the back-breaking European galleys. Both European and Maghrebi corsairs or privateers had licences from their governments, and they paid tax on their captures and attacked only official enemies. The trade in captives and ships depended on vibrant economies on both sides of the Mediterranean. This commerce drew European merchants, travellers and traders to take up residence in the Maghreb, and encouraged European powers to make treaties of peace and trade with Maghrebi states – to exchange ambassadors, share information, and send lavish gifts to one another. These relatively stable relations of states, peoples and economies existed – at least for the British – throughout the late 17th and 18th centuries, all the way up to Europe’s 19th-century colonial conquests.

To understand this complex world, let’s take a look back at a network of British residents – men, women and children – who lived in Algiers, Tunis and Tripoli in the late 17th century. We’ll see how, after decades of conflict, they engaged with the cultures around them, built new lives for themselves, and paved the way for peace and trade between Britain and the Maghrebi states.

In late 1694, the British consul in Algiers Thomas Baker travelled eastwards with his friend Sha’ban, the dey of Algiers, at the head of a conquering army. Baker planned to exploit his local connections to ransom the last British slaves on the Barbary Coast, negotiate revisions to the existing British treaty with Tripoli of 1662, and return to England in triumph. In Algiers, Baker’s protégé, the merchant Robert Cole, remained at home with Baker’s wife Deborah and their two small daughters. Meanwhile, once in Tunis, Baker reunited with his old housemate, the consul Thomas Goodwyn, the consul’s wife Edith and their daughter Urania. Then, leaving the Goodwyn family in Tunis, Baker arrived in Tripoli only to narrowly miss the consul Nathaniel Lodington and his wife Jane, along with their servants Gabriel, Frances and little Molly D’Ortega, who had all temporarily left for Malta. So Baker hammered out new treaty provisions with the dey and pasha of Tripoli, promising lavish gifts, and returned to Sha’ban’s camp in Tunis to celebrate. Those new British treaties with the Ottoman Maghreb, signed in 1694, would hold for more than a century.

Just a few decades before Baker’s trip, the situation had been very different. In the 1620s and ’30s, British naval ships bombarded the town and kasbah of Algiers, the powerful Levant Company withdrew all its assets from the region after repeated corsair attacks, and Algerian corsairs captured the Isle of Lundy in the Bristol Channel and abducted more than 200 villagers from Baltimore in Ireland. In the 1640s, popular petitions for King Charles I to ransom captured Britons and beef up the Royal Navy to protect shipping attracted thousands of signatures, contributing to the English Civil War and the king’s execution for treason. British captives in the Maghreb were reputed to suffer enslavement, beatings and forced conversion to Islam. But many thousands of Britons freely changed sides, swayed by the power, wealth and opportunity they found in Ottoman lands. Even after the landmark treaties between Britain, Algiers, Tunis and Tripoli in 1662, four brutal wars with Algiers and Tripoli saw thousands of British captives taken, vast tributes and ransoms paid, and the release of numerous lamenting captivity narratives.

‘Enslaved Christian prisoners are sold in a square in Algiers’ (1684) by Jan Luyken. Courtesy the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Despite enthusiastic British hopes for the military settlement at Moroccan Tangier, transferred from the Portuguese at Charles II’s marriage to Catherine of Braganza in 1662, it would not come to fruition. The British settlement’s prospects faded in the face of repeated Moroccan sieges and internal strife. For merchants and consuls officially allowed to live in Ottoman-controlled Algiers, Tunis and Tripoli, the situation remained challenging: in 1664, the consul Thomas Browne in Tunis complained to his British superiors about famine, plague and trade restrictions; and, 13 years later, two decades of Tunisian civil wars and repeated invasions from Algiers and Tripoli repeatedly threatened their safety and business.

An English Ship in Action with Barbary Vessels (1678) by Willem van de Velde. Courtesy Royal Museums Greenwich

The consul would regularly visit his next-door neighbour, the dey, to gossip over ‘a dish of Coffe’

By the late 17th century, Algiers, Tunis and Tripoli were all semi-autonomous provinces, ‘regencies’, of the Ottoman Empire. Pledging nominal allegiance and military support to the Sultan, they managed many of their own affairs, particularly when it came to foreign trade, diplomacy and, above all, corsairing: the state-licensed piracy practised on all sides of the Mediterranean since the medieval era. The typical form of corsairing was Christians against Muslims, and Muslims against Christians. By virtue of their religious differences, the regencies considered themselves to be at war with all Christian powers by default, unless treaties were negotiated, captives ransomed, tributes paid, and only as long as these rules were then obeyed. The 1662 treaties had promised that Britons would treat Algerians, Tunisians and Tripolitans ‘with all possible respect and friendship’, redeem all the slaves at ‘the price they were first sold for in the market’, and carry passports certifying their nationality, to be checked at sea by corsair crews. In return, British ships would be exempt from attack, resident British traders would be free to practise their religion, and free from various forms of physical and financial persecution, and all trade would be subject to set taxes.

Ratification by King Charles II of the treaty between Great Britain and Algiers, 1663. Courtesy the National Archives, Kew, SP 108/2/5

These agreements, however fragile, marked an important shift. Instead of a default state of conflict, subsequent wars between Britain and the Maghrebi states required treaty violations and diplomatic breakdown to begin. Rather than being immediately imprisoned, extorted, deported or punished for their countrymen’s misdeeds, British residents in the Maghreb enjoyed privileges and rights that helped them negotiate and manage disputes. Rising British naval power encouraged Maghrebi states to focus their energies elsewhere, but the treaties also reflected an increasing appetite for trade, mutual learning and cooperation on both sides. As a result, British merchants began to establish robust networks and families on the coast of the Maghreb, heralding a new era in British-Maghrebi relations.

Increasingly from 1662, British merchants were able to live freely and securely in Maghrebi societies without pressure to convert. They established close relationships with Muslim and Jewish powerbrokers, and built robust networks across the Mediterranean, sending letters, news, goods and people in all directions. In 1680, for example, Baker, then British consul in Tripoli, called the Muslim corsair captain Cara Villy Rais ‘my particular friend’. In 1695, Cole, the consul in Algiers, would regularly visit his next-door neighbour, Dey Hadj Ahmed, to gossip over ‘a dish of Coffe’ and admire the lavish treasures the dey received from European negotiators. On several occasions, Cole housesat for Ahmed.

In order to trade, merchants and consuls employed local translators, mediators and buyers. In the course of developing business relationships, Cole, like others, got to know and befriended various local officials, merchants and religious leaders. Keeping them all on side was sometimes an impossible task, as the Irish merchant in Tunis James Chetwood found in 1697 when trying to get official permission to buy and export grain, the staple commodity Britons transported from Tunisia to Europe. In this ‘more & more intricate & uncertaine’ enterprise, Chetwood bought off in succession eight or nine different local officials, calling them ‘Rascally’, ‘insatiable’, ‘greedy & Malicious’, before ‘a whole shole of pittifull dogs Appear’d, and laid in theire pretences’.

The increasingly stable peace between Britain and the Barbary states meant that opportunities for trade in the latter half of the 17th and into the 18th century were more available than ever. With British ships safe from corsair attacks, and diverse products to import and export, British merchants in the Maghreb formed wide and diverse commercial and personal networks. Goodwyn kept more than 3,000 letters from more than 600 different people in at least 60 cities from his 21 years living as merchant and consul in Tripoli and Tunis between 1679-1700. For some merchants, moving to the Maghreb became no more dangerous than moving to Catholic Europe: there were some threats, particularly relating to their Protestantism and sometimes to climate, but far more opportunities.

Goodwyn never seems to have learned Arabic or Ottoman Turkish, but other British residents certainly did, which allowed new and deeper knowledge about the Maghreb. Previously, captives were the only Britons experienced enough in Maghrebi life to acquire detailed knowledge of its life or to publish accounts. Captive narratives are tricky documents for historians: because the captives’ movements were constrained, they were usually hostile to Islam and their Muslim captors, and they were written for a British reading public, so writers were often concerned to portray their own bravery, loyalty to Britain and persistence against attempted forced conversions. However, soon after treaties were negotiated in 1662, British residents began writing detailed reports about Maghrebi news to merchant colleagues and government officials around the Mediterranean and Britain. Many of these reports ended up published in new British newspapers such as The London Gazette, where readers could find rich detail on Maghrebi ethnic, political and religious diversity, as well as diplomatic and economic connections with Europe.

In 1675, the consul in Algiers Samuel Martin learned to read, write and speak Arabic, and interviewed government officials, soldiers and judges to write The Present State of Algiers. This work provided in a convenient and concise package details on Algerian history, economy, military and naval organisation, ethnic diversity, territorial control and foreign trade, all useful for the promotion of cooperation between Britain and the regency. Published in London three times in the next five years, Martin’s work helped bring new knowledge of the Maghreb to Britons.

Some enslaved women raised money for their own ransoms, others converted to Islam and married powerful leaders

Later, merchants learned local languages in daily life, as part of their training: in 1696, when the Algiers consul Robert Cole brought over his nephew Wyndham Cole to be his apprentice, he promised Wyndham’s mother:

if his genious leads him to it make him master of the Turkish & Arabian that of Spanish and Italian will come of Cource & may lerne what other Languidge he pleases.

Likewise, they learnt how to navigate the various religious and cultural issues that attended international business: for example, in September 1683, Goodwyn and his partners were repeatedly frustrated by the coincidence of Ramadan, Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, which together meant neither the Islamic nor the Jewish communities were willing to trade. By 1694, they were hosting annual drunken parties for ‘the Severall Officers of the Divan, Bashawes, Beyes, & Deyes’ (ie, the Algerian ruling council, Ottoman governors, cavalry commanders-turned-regional authorities, and janissary commanders-turned-urban rulers) at Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Adha (ie, the two major holidays in the Ottoman-era Islamic calendar).

Once British commercial ventures had stabilised and started to show profits, merchants and consuls began to start families in the Maghreb. The earliest British women had arrived decades before, in the early 17th century, but unwillingly, as captives. In their book Britain and the Islamic World, 1558-1713 (2011), the historians Nabil Matar and Gerald MacLean explain these women’s unique challenges, and explore how enslaved Britons tried to improve their condition. Some raised money for their own ransoms, and others converted to Islam and married powerful leaders: a poor British woman became the most-honoured wife of Mawlay Isma’il, Lella Balqees, holding great influence for several decades; another married the dey of Algiers; and another became mother to the celebrated and dashing Muhammad ben Haddou, the Moroccan ambassador to Britain in 1681-82.

These women rose higher than any captured male Briton, writes Matar elsewhere, realising that ‘Barbary could provide them with opportunity and advancement[, to] acquire agency and leave their mark’ in a society that allowed them to ‘be fully integrated’. But, according to Matar and MacLean, very few British women took the opportunity to move by choice. In fact, the historians argue that we can measure the strength of British-Maghrebi relations by the presence of free British women there, and it paints a bleak picture: they can find no British women voluntarily migrating, except to English Tangier, before the 1750s, by which time the British Royal Navy had so much naval power that war with the Maghreb was no longer a significant threat. However, my research has shown that free British women were present much earlier, suggesting that British-Maghrebi relations began to improve long before.

Before the advent of extended peace in 1662, male merchants tended to live together in the Maghreb to make money before returning home to get married. Or if, like the Algiers consul Samuel Martin, they were married already, they left their wives and children behind in Britain. The first British families to start in the Maghreb were somewhat unconventional, compared with their equivalents in Britain, driven by happenstance, opportunism and, above all, the agency of creative, determined and trailblazing women. Edith Stedham came to live in Tunis at some point before 1679, having been abandoned by her husband, and established herself as a trustworthy and respected member of the otherwise entirely male British consulate community.

By 1683, Stedham had emerged as a trader in her own right, importing fine English cloth for sale in Tunisian markets, and advising the consul on official business. Soon after, Goodwyn became consul at Tunis, and he and Stedham began an intimate relationship. By mid-1685, he trusted her to manage the consulate while he travelled on business; in September, she gave birth to their daughter Urania, the first child born to free British residents in the region. Stedham soon became the matriarch of the British community, supervising junior merchants, purchasing land with Goodwyn, and personally investing hundreds of pounds in wheat and cloth. By January 1693, Goodwyn and Stedham had finally married, and her position was secure, but their marriage lasted only two years: in March 1695, Stedham abruptly died, to the lament of Christian and Muslim colleagues around the Mediterranean.

From her young childhood, Urania Goodwyn was well regarded by residents in the British community and their visitors, and her father doted on her, raising her from the outset with Maghrebi, European and British cultural influence. While Urania was a child and young teenager, and particularly after her mother’s death, her father and Chetwood, his merchant partner, took joint responsibility for her upbringing, encouraging her to read and write (in English and possibly Italian), socialise and learn household management, arranging playmates for her, buying her Algerian ribbons and gold jewellery, and simultaneously seeking to return her home to receive maternal input. While they waited for official permission to return to Britain, Goodwyn provided a maternal figure of sorts in Jane Lodington, wife to Nathaniel Lodington, who with the D’Ortegas left Tripoli for Malta and then decamped to Tunis; the two families lived together in Tunis for nearly two years from 1695-97 and formed a close bond, planning to move home and live close by in England.

After the Lodingtons’ return to Tripoli, Goodwyn arranged for Urania’s aunt Dorothy Newark and cousin Lucy Newark to visit Tunis in 1698-99 as tourists (among the first British women to do so), connecting Urania to her extended family and to European fashions and customs, including French hairstyles and Spanish guitar. He also fended off a marriage proposal from Benjamin Lodington, the new Tripoli consul (1700-30), who was decades older, had never met Urania, and was known for sexual misconduct with various mistresses.

While they were separated, the Goodwyns and the Lodingtons and D’Ortegas regularly wrote letters and sent gifts to each other, before they were reunited in London. Urania lived out her life unmarried, dying in 1742, but to the end retained connections to the Maghreb, leaving three ‘Turkish’ coins in her will. The Stedham-Goodwyn family, living in peaceable Tunis, blazed an unconventional trail that others could follow.

Both Edith and Deborah, alongside their eventual husbands, saw the Maghreb as a site for advancement

The Baker family in Algiers started in similarly unusual circumstances. In late 1692, Thomas Baker, the Algiers consul, became engaged, in his early 50s, to 25-year-old Deborah Bourne née Robinson, recently widowed by her husband’s sudden death as he carried letters from Baker to Europe. Chetwood informed Goodwyn by letter:

there has been a long intimacy between ye lady & ye Consull, & a pretty little Girle in ye Case; the Gentlewoman is fine fatt & luscious, & makes a goodly figure.

In other words, Baker and Bourne had enjoyed an extramarital affair. They had also conceived a daughter, Honora. Bourne and Baker were married by January 1693, and Baker wrote poetically about his surprise at being married and starting a family so late in life:

Tis a Worl I little though at this time of day to bee soe very neerely relate to, But ’twas Love, Mighty Love, would showld its Power, and spightfully done it was, of that Peevish Deity to putt me upon working for a family towards ye close of the day.

After Baker had left for Tripoli in 1694, his second daughter was born, and named Deborah like her mother. The Algiers consul Robert Cole was her godfather, and he provided Baker with a tender report on the progress ‘of [those] so dear to you’: Honora, ‘thundring girle, wants very littell of walkeing alone but not a tooth nor line of any’; little Deborah, who was well again after a short sickness; and Deborah senior who ‘wants nothing but your Company to make her the happyest of all her sects’. Cole concluded with best wishes for Baker’s return home, ‘for in truth Sr wee all want you, and cant live with out you’.

Like Edith Stedham, Deborah Baker was an important figure in the British community – she managed her own vineyard and tavern in Algiers, procured local and European goods for household use, and organised lavish presents for visiting British naval officers. Both Edith and Deborah, alongside their eventual husbands, saw the Maghreb as a site for advancement, and made the most of their residence there.

The Baker family left Algiers for England in early 1695, leaving Cole to feel desperately lonely. Since he’d arrived in 1679, he had tried repeatedly to convince his own wife Mary to move to Algiers. In 1695, he recommenced his entreaties, but she continued to refuse: in 1712, he died in Algiers, and left his estate entirely to her. Similarly, in 1693, Chetwood, the Irish merchant, was courting Phoebe Haye, and hoped she would move to Tunis with him, promising her mother that ‘such a propposition … has been imbrac’d by others of no despicable rank & circumstances’ and that, if she would move there and wed him, he would ‘cherrish her as his own soul’. But Chetwood and Haye remained unmarried; still, when he died in Tunis in 1699, he left her some £1,500, one-third of his estate.

Through the unconventional Goodwyns and Bakers, and despite Mary Cole and Phoebe Haye’s reluctance to migrate, a shift towards British women living freely in the Maghreb had begun. From 1711, the consul Richard Lawrence lived with his two sisters and brother in Tunis for more than two decades until their respective deaths, and Benjamin Lodington’s daughter Susannah was born in Tripoli in 1709.

As British trade with the Maghreb increased, and British naval power grew in the Mediterranean, so too did its consuls and merchants’ clout in Britain and abroad. They were able to rent more elaborate houses in the Maghreb, clothe themselves in fine silk suits and Ottoman waistcoats, and drink French wine with their couscous and roast beef. They began to enjoy the warm weather, fine gardens and rich hunting grounds the Maghreb offered, sometimes to the extent that it reflected badly on Britain: in 1700, after returning to England, Nathaniel Lodington lamented to Thomas Goodwyn:

The sattisfaction I thought to finde in England was more in ye exspectation then I have found itt to be Since my arriveall … [partly] by reason of the cold moist weather, not verry agreeable to us who have bene used to a warme Country which I thinke is pleasantest.

British consuls in Europe and the Ottoman Empire managed only business affairs, while ambassadors handled international disputes and treaty negotiations. Consuls in the Maghreb often combined both roles, and traded for themselves as well. This gave them more influence over international affairs. In addition to Thomas Baker renegotiating the treaty with Tripoli in 1694, in 1686 Goodwyn reconfirmed the British-Tunisian treaty, in 1693 Baker settled a diplomatic dispute between Algiers and Genoa, and in 1701 Robert Cole mediated a peace between the Algerians and Moroccans. Consuls and merchants also began to use their clout to advance their families: in 1701, Cole thanked his superior James Vernon for procuring a royal audience for his apprentice and nephew Wyndham Cole, who delivered an Algerian saddle to the king and, in 1703, Baker arranged for Wyndham to house some escaped Turkish slaves at government expense, and then to carry Queen Anne’s present to the dey of Algiers. In 1699, Goodwyn procured Lucy Newark, returning home from her visit in Tunis, a similar opportunity:

The Beyes & Deyes letters to our King shall most Certainly accompany your neece, and with Mr Steele [Goodwyn’s colleague in London] shee’le agree how to manage so as to enjoy some advantage by [th]em&.

They were also able to gain positions for themselves, their friends and their partners. Goodwyn’s merchant partners in London delivered his consular reports to the monarch and secretary of state, and lobbied them privately about salaries, expenses and diplomatic disputes. Baker, for his part, used his reputation – built over decades of trade in the Maghreb and through consulships in Tripoli and Algiers – to establish himself after returning home as a leading government adviser on Maghrebi affairs, where he could protect and support his protégé Cole, and eventually to secure a lucrative and influential 10-year stint as commissioner for prizes, managing the repurposing of captured foreign ships during the War of the Spanish Succession. When he retired in March 1715, Baker had achieved great wealth and prestige, such that in the same year he could marry off his daughter Honora to a future viscount.

Between the early and the late 17th century, the prospects for Britons in the Ottoman Maghreb changed. Beginning with the landmark treaties negotiated in 1662, British merchants established networks and trade links, built cultural and linguistic knowledge, and shared that knowledge with colleagues, superiors and the general public at home. As soon as they felt securely established, they started to establish families, together enjoying the climate and culture. Both men and women were able – by their knowledge, experience and networked clout – to advance themselves into high positions in business, government and even the nobility. The Maghreb had transformed, from a land dominated by corsairs and captives to a fertile and intriguing international partner. For a century before the age of European colonisation in the Maghreb, Britons and Maghrebis coexisted in relative peace.