After 12 years of fascism, six years of war, and the concentrated genocidal killing of the Holocaust, nationalism should have been thoroughly discredited. Yet it was not. For decades, nationalist frames of mind continued to hold. They prevailed on both sides of the so-called Iron Curtain and predominated in the Global North as well as in the developing world of the Global South. Even in the Federal Republic of Germany, the turn away from ‘the cage called Fatherland’ – as Keetenheuve, the main character in Wolfgang Koeppen’s novel The Hothouse (1953), called his depressingly nationalistic West Germany – didn’t commence immediately.

When the turn did begin, however, Keetenheuve’s country would set out on a remarkable journey – not one racing down the highway to cosmopolitanism, but rather a slow one that required a series of small steps leading to the gradual creation of a more pacific, diverse and historically honest nation – a better Germany.

After the collapse of the Third Reich, Germans widely blamed other countries for the Second World War. ‘Every German knows that we are not guilty of starting the war,’ asserted the Nazi journalist Hildegarde Roselius in 1946. With ‘every German’, this acquaintance of the American photographer Margaret Bourke-White certainly exaggerated. But in 1952, 68 per cent of Germans polled gave an answer other than ‘Germany’ to the question of who started the Second World War, and it was not until the 1960s that this opinion fell into the minority.

In the mid-1950s, nearly half of all Germans polled said ‘yes’ to the proposition that ‘were it not for the war, Hitler would have been one of the greatest statesmen of the 20th century.’ Until the late 1950s, nearly 90 per cent gave an answer other than ‘yes’ when asked if their country should recognise the Oder-Neisse line, the new border with Poland. Perhaps most revealing of all was their stance on Jews. On 12 June 1946, Hannah Arendt hazarded the opinion to Dolf Sternberger, one of occupied Germany’s most prominent publicists, that ‘Germany has never been more antisemitic than it is now.’ As late as 1959, 90 per cent of Germans polled thought of Jews as belonging to a different race – while only 10 per cent thought of the English in these terms.

The sum of these attitudes suggests that Keetenheuve’s cage called Fatherland remained shut for more than two decades after the fall of the Third Reich.

Like most of Europe and indeed the world, Germany lacked a powerful alternative discourse to nationalism. Until the 1970s, the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights possessed little traction in postwar Europe. Regional affiliations, such as those to Europe (or Pan-Africanism or Pan-Arabism), were more viable but as yet confined to a small number of elites. Strident defences of capitalism also did little to deplete the store of nationalist tropes. And on the western side of the Iron Curtain, anti-Communism supported rather than undermined Nazi-inspired nationalism.

The postwar world was, moreover, awash in new nation-states, especially as it shaded into the postcolonial era. In 1945, there were only 51 independent countries represented at the UN: 30 years later, there were 144. Whether in Jawaharlal Nehru’s India or Kwame Nkrumah’s Ghana, nationalism and promises of self-determination fired anti-colonial independence movements in Asia and Africa. In Europe, nationalism also continued to shape claims to group rights and territorial boundaries. In Germany, divided and not fully sovereign until 1990, it informed discussion over eventual unification, the right of the ethnic German expellees to return to their east European homelands, and the validity of Germany’s eastern borders. Indeed, it wasn’t until 1970, a quarter-century after the war, that the Federal Republic of Germany finally recognised as legitimate the German border (established at the Potsdam Conference in 1945) with Poland. And still nearly half the citizens of West Germany opposed the recognition.

The habits of thought of a once-Nazified nation-in-arms constituted one set of reinforcements

The pervasiveness of exclusionary nationalism in the postwar period also reflected a new underlying reality. The Second World War had created a Europe made up of nearly homogeneous nation-states. A series of western European countries, now thought of as diverse, were at that time just the opposite. The population of West Germany who were born in a foreign country stood at a mere 1.1 per cent, and the minuscule percentage proved paradigmatic for the tessellated continent as a whole. The Netherlands had a still smaller foreign-born population, and foreigners made up less than 5 per cent of the population in Belgium, France and Great Britain. In the interwar years, eastern European countries such as Poland and Hungary had significant ethnic minorities and large Jewish populations. In the postwar period, both were all but gone, and Poles and Hungarians were largely on their own.

Nor, in the trough of deglobalisation, did Europeans often get beyond their own borders, and Germans were no exception. In 1950, most Germans had never been abroad, except as soldiers. Some 70 per cent of the adult women had never left Germany at all. Travel, a luxury enjoyed by the few, didn’t begin to pick up until the mid-1950s, while international travel became a truly mass phenomenon only in the 1970s, when most people had cars of their own. In the first decades of tourism, Germans mainly visited German-speaking destinations, such as the castles on the Rhine or the northern slopes of the Alps. In these decades, few Germans, save for the highly educated, knew foreign languages, and most other Europeans, unless migrant workers, were no different.

The cage called Fatherland was thus reinforced. The persistence in a world of nationalism of the habits of thought of a once-Nazified nation-in-arms constituted one set of reinforcements. The relative homogeneity of postwar nations and the lack of peacetime experiences abroad constituted another. There was also a third reinforcement keeping the cage shut. This was that Germans had something to hide.

In the postwar period, Germany was full of war criminals. The European courts condemned roughly 100,000 German (and Austrian) perpetrators. The sum total of convictions by the Second World War allies, including the United States, the Soviet Union and Poland, pushes that number higher still, as does the more than 6,000 offenders that West German courts would send to prison, and the nearly 13,000 that the much harsher judicial regimen of East Germany convicted.

Nevertheless, there was still a great deal left to cover up. Lower down the Nazi chain of command, a dismaying number of perpetrators of various shades of complicity got off without penalty or consequence. Two jarring examples might suffice. Only 10 per cent of Germans who had ever worked in Auschwitz were even tried, and only 41 of some 50,000 members of the murderous German Police Battalions, responsible for killing a half a million people, ever saw the inside of a prison.

Trials and sentences reveal only part of the story of complicity. Many Germans not directly involved in crimes had come into inexpensive property and wares. Detailed reports from the north German city of Hamburg suggest that, in that one city alone, some 100,000 people bought confiscated goods at auctions of Jewish wares. Throughout the Federal Republic, houses, synagogues and businesses once belonging to Jewish neighbours were now in German hands. Mutatis mutandis, what was true for the number of people involved in the murder and theft activities of the Third Reich also held true about what people knew. ‘Davon haben wir nichts gewusst’ (‘We knew nothing about that [the murder of the Jews]’), West German citizens never tired of repeating in the first decades after the war. Historians now debate whether a third or even half of the adult population in fact knew of the mass killings, even if most scholars concede that few Germans had detailed knowledge about Auschwitz.

The Germans shared a European fate here as well, even if they had the most to hide. In his trailblazing article ‘The Past Is Another Country: Myth and Memory in Postwar Europe’ (1992), the late Tony Judt pointed out the stakes that almost all of occupied Europe had in covering up collaboration with Nazi overlords. This wasn’t merely a matter of forgetting, as is sometimes assumed. Rather, it involved continuing and conscious concealment. After all, many people (especially in eastern Europe, where the preponderance of Jews had lived) had enriched themselves – waking up in ‘Jewish furs’, as the saying went, and occupying Jewish houses in what was surely one of the greatest forced real-estate transfers of modern history.

For all these reasons, the cage called Fatherland wasn’t easy to leave and, rather than imagine a secret key opening its door, it makes more sense to follow the hard work involved in loosening up its three essential dimensions: a warring nation, a homogeneous nation, and a cover-up nation. It wasn’t until West Germans could take leave of these mental templates that they could even begin to exit the cage. Fortunately, in the postwar era, Germany was blessed with prolonged prosperity, increased immigration, and the passing of time. When brought together with small, often courageous steps of individuals and institutions, these factors allowed West Germans eventually to embraced peace, diversity and the cause of historical truth: in short, to exit the cage.

Typical of nations cognitively still at war, the problem for many Germans was perceived treason

The vision of ‘a living, not a deathly concept of Fatherland’, as Dolf Sternberger put it in 1947, had already been laid in the early years of occupation. Sternberger, who cut off the ‘A’ from his first name, argued for a different kind of nation, one that commanded openness and engagement but didn’t end in the glorification of killing and dying in war or in the marginalisation and persecution of others. The nation as a source of life, as a caretaker of its citizens, and not as a vehicle for power, expansion, war and death: this was Sternberger’s initial vision.

It was a conception of Germany that West Germans slowly embraced, symbolically replacing the warfare state with the welfare state, swapping barracks and panzers for department stores and high-performance cars. Enabled by a velvet transition in which GDP per capita essentially quadrupled between 1950 and 1980, Germans came to conclude that their recent democratic past was far preferable to even the peace years of the Third Reich. Forgetting how solid and confining the cage was in the immediate postwar period, contemporary critics often scoffed at this shallow embrace of ‘fair-weather democracy’. Yet with a wider aperture, we now know that prosperity, and the absence of war, is the fundamental precondition of the global transition to democracy, most of which has transpired in the postwar era. In 1939, roughly 12 per cent of the population of the world lived in democracies, but by the end of the 20th century nearly 60 per cent did.

Germany’s slow exit from a nation-at-arms mentality was essential to it joining the democracies of the world. But the exit was by no means easy. The contentious memorialisation of the conservative resisters who’d tried and failed to assassinate Hitler on 20 July 1944 is instructive in this context. In 1951, some 40 per cent of Germans said that they were for the resisters, while some 30 per cent were against them, with the rest ignorant of the so-called Operation Valkyrie or unsure. Typical of nations cognitively still at war, the problem for many Germans was perceived treason during wartime. This was especially true of men. More than half of all German men thought that the assassination attempt was morally wrong. And even of those who did approve of it, a significant number thought that the resisters should have waited until after the war.

The persistence of this nation-at-arms mentality shadowed one of the most contentious issues of the early Federal Republic: the reconstitution, in 1955, of an army. A broad coalition, ranging from church organisations to trade unions, emerged to warn against the resulting remilitarisation of German society. When it became clear that the army would be revived, the same activists worked to ensure that soldiers be ‘citizens in uniform’ ready to refuse patently unethical orders. In conception, then, the new army, the Bundeswehr, personified the rejection of Prussian and Nazi traditions. Yet some 80 per cent of the officers of this newly created federal defence had once served in the Wehrmacht, the armed forces of Nazi Germany.

The basic coordinates of the nation-at-arms held – as it would for the first quarter-century after the end of the Second World War. Gradually, however, Europeans ‘invented peace’, in the words of the military historian Michael Howard, and came to think of war as an unnatural state, unbefitting civilised societies.

The debate was not if foreign workers should be allowed to stay, but under what terms and with what support

In postwar Germany, conscientious objection to military service was a reliable index of this new regard for peace. In the first years of the Bundeswehr, almost all the young men who were drafted showed up for duty. But by the early 1970s, the number of applications for recognition as conscientious objectors climbed above 20,000, and would continue to climb throughout the 1970s and ’80s, so that in the two years before unification, the number of applicants was close to 80,000. By this time, German peace movements, reacting to the Superpowers making the two Germanies into armed camps, had eroded the prestige of all things military among young people. By 2000, Germans were among the least willing to pick up arms and fight for their country: only a third of those polled said they would do so.

The exit from the cage called Fatherland also took longer for those who saw belonging in terms of ethnicity and conceived of nations as ethnically homogeneous units. This second exit also started later than the confrontation with Germany’s militarist past and, ironically, it was the building of the Berlin Wall on 13 August 1961 that powerfully accelerated it. Intended to end East Germany’s haemorrhaging of qualified young people to the West, the wall inflamed national passions in the short term, but not in the long run. The next generation of young West Germans came to see the solution of ‘two-states, one nation’, as West Germany’s chancellor Willy Brandt would later put it, as permanent. The wall also accelerated West Germany’s efforts to bring in Gastarbeiter (guest workers), as the massive influx from East Germany (more than 3 million people between 1945 and 1961) suddenly came to a halt.

A Turkish family leaving for their annual holiday in Turkey is waved off by neighbours in Essen, West Germany, in 1982. Photo by Henning Christoph/ullstein bild via Getty

As if with the turns of a kaleidoscope, the ethnic constellation of West Germany began to change, at first slowly, then rapidly. The so-called Worker Recruitment Stop of 1973, meant to reduce the influx of foreigners to a trickle, actually doubled the number of workers coming to West Germany and encouraged them to bring their families. By 1982, with West Germany still reeling from the Oil Crisis and unemployment hovering at 10 per cent, the country suddenly had a foreign-born population of 7.5 per cent. Almost 80 per cent of West Germans thought that too many foreigners now lived in their country. Even 60 per cent of West Germans identifying with the new Green Party held this opinion.

A debate, which continues until this day, had already emerged about the degree to which West Germany had become what Heinz Kühn, commissioner for foreigner affairs in Helmut Schmidt’s government, would call ‘an immigrant nation’. An irreversible situation had occurred, Kühn wrote in 1979, and ‘those who are willing to stay … must be offered unconditional and permanent integration.’ The Kühn Memorandum, forgotten about by all except specialists in German immigration history, effectively shifted the ground of the debate – not whether foreign workers should be allowed to remain in Germany, but under what terms and with what support. It also furthered an incipient discussion about the extent to which foreigners were not guests but Mitbürger, fellow citizens.

In the life of nations, small openings can have profound effects. In these postwar years, general prosperity allowed Germans to travel as tourists, not as soldiers, and indeed no major European nation supplied so many tourists to other European nations as West Germany. More important, prosperity continued to draw workers to the Federal Republic. By the end of the century, a united Germany would have a foreigner population roughly eight times as large as it had in 1950; in percentage terms, the foreign-born population in the year 2000 was not far behind that of the US.

Yet if the insularity of earlier decades was gone, ethnic segregation remained, and anti-foreigner sentiment continued to poison the private and public sphere alike. Indeed, after unification in 1990, it erupted in greater violence than ever before. Beginning in cities in the east where unemployment was high, prospects bleak and experiences with foreigners limited, vicious and often lethal anti-foreigner violence occurred in Hoyerswerda, Dresden, Rostock-Lichtenhagen, and many other communities, and soon spilled into west Germany. By 1993, anti-foreigner extremists had murdered nearly 50 non-Germans and, by the end of the decade, more than 100.

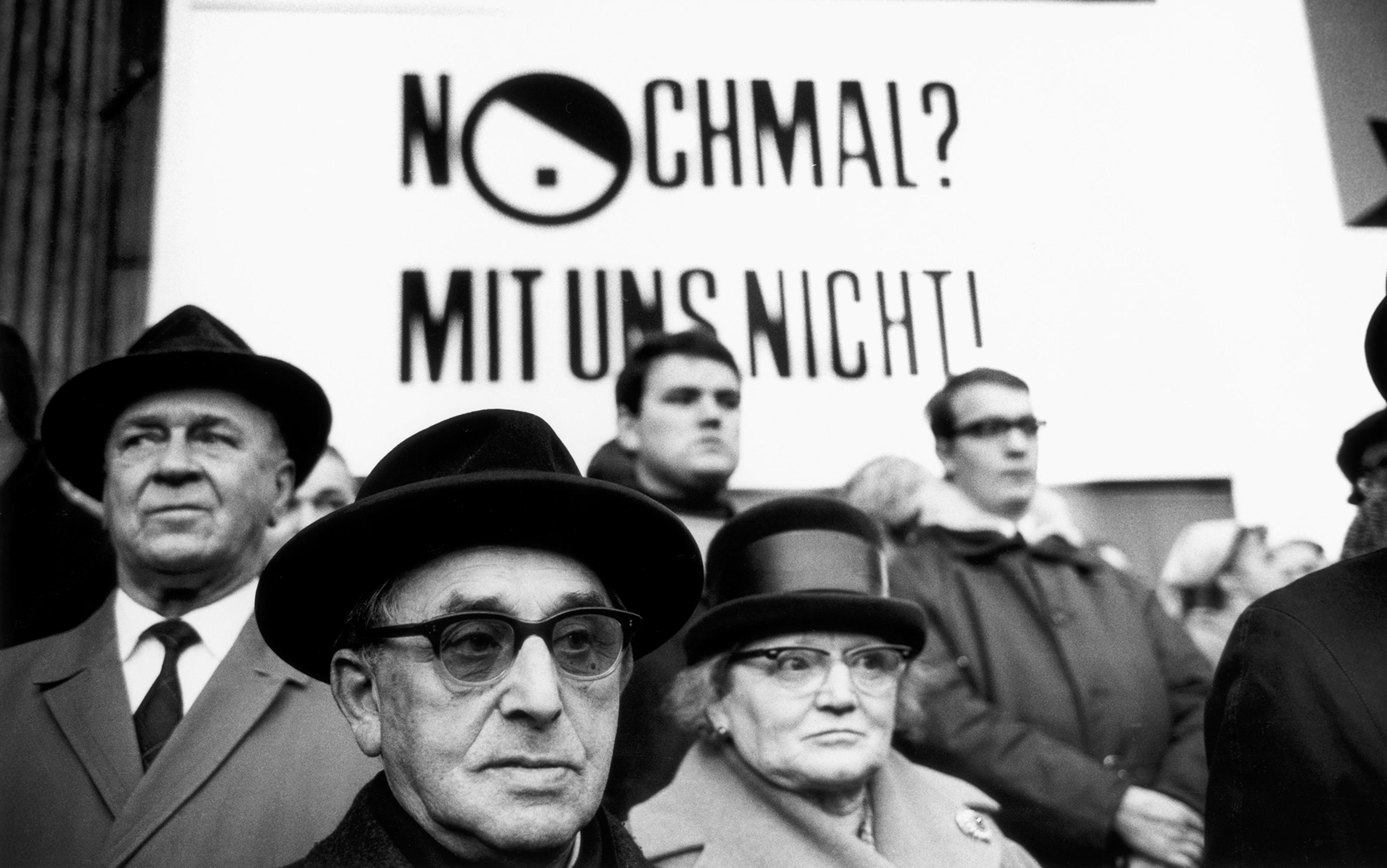

Was the concept of an immigrant nation at an end, as many warned? The best evidence suggests otherwise. In reaction to the killings, hundreds of thousands of German protesters (more than a million in some estimations) went out on to the streets in order to publicly oppose the violence. They were men and women of all ages, walks of life and political persuasions. Many had never demonstrated before. But they wanted the world to know that ‘This is not who we are.’ The ‘we’ was important to them. For theirs was an appeal against the xenophobic nationalists in their midst and for a more inclusive nation. And by the end of the 1990s, this general appeal began to transform into hard policy. In 2000, new citizenship regulations reflected the new inclusive discourse by making significant concessions to jus soli, the idea that you are a citizen of the place where you are born, as opposed to jus sanguinis, the older German measure, defining citizenship by blood. Almost immediately, roughly a million immigrants became German citizens. Since the mid-1990s, bi-national marriages have doubled, making up more than 7 per cent of all heterosexual marriages in Germany. The new immigration nation was far from being uncontested terrain, however, as the rise of xenophobic populists in the midst of the refugee crisis of 2016 showed. And yet here, too, as in the 1990s, the number of Germans who came out in order to publicly demonstrate for tolerance and lend a helping hand was commendable.

The patient work of commemoration missing in earlier decades was now being pursued with a vengeance

The most remarkable transformation was, however, the third: how Germany faced its past. It didn’t face it right away. Certainly, it’s defensible to argue that it wasn’t until the major war trials had passed, and the restitution of property was regulated and settled, that a genuine and honest turn to the past could even begin. Following this logic, one might have expected a surge of interest in the National Socialist past after the trials of the late 1950s and early ’60s. But in the late 1960s, passionate conviction, not patient reconstruction, was the order of the day, and political ideology, rather than deepening historical analysis, often occluded insight. It remains controversial to assert that serious and sustained interest in the National Socialist period didn’t take off in the late 1960s, and that, instead, a ‘second forgetting’, as one leading West German historian has described the 1970s, set in.

An interpretation that de-emphasises the breakthrough of the late 1960s puts the turn at the end of the 1970s and the beginning of the ’80s, as four events converged. The first was the 40th anniversary in 1978 of the November Pogrom (Kristallnacht) of 1938; it brought forth a great number of commemorations, especially in West Germany’s larger cities. The second was the airing of the US TV miniseries Holocaust (1978). As many as 20 million Germans, mainly in the Federal Republic, saw some part of it, and its very narrative structure invited them to identify with the main character – the intrepid Inga Helms Weiss, played by Meryl Streep, who married into a Jewish family and did everything she could to save them. The third event, less often discussed, was the end of a two-decades-long debate about the statute of limitations for Nazi crimes, with a close vote in the West German parliament – 255 for the cancellation of such legal shields, 222 against – allowing West Germany’s authorities to continue the hunt for Nazis guilty of murder. And finally, the fourth event: a major, nationwide essay contest for high-school students in 1981, with some 13,000 submissions on the subject of ‘Everyday Life in National Socialism’.

The confluence of these four events created a tsunami effect. Research – in schools and communities – soared. Across the country, literally thousands of schoolteachers, archivists, retirees, interested citizens and school students – such as the real-life Anna Rosmus, whose story was told in Michael Verhoeven’s film The Nasty Girl (1990) – dug into local records and researched what happened in their own communities, often working with Jewish people who’d once lived in these cities and towns and were now in Israel, France, Great Britain, Argentina or the US. Suddenly, the patient work of commemoration that had been missing in earlier decades was being pursued with a vengeance. People restored synagogues, exposed abandoned barracks that had once been used to house forced labourers, and discovered literally hundreds of subcamps of concentration camps throughout the German countryside. They held speeches, wrote articles, published books. Hardly any town in Germany with a population over 20,000 and where Jews once lived is now without an account of what happened then, and what fate befell the Jews who lived there – former Jewish Mitbürger, as many Germans now began to call them.

The story of how Germany faced its past has been told often, most recently in Susan Neiman’s book Learning from the Germans: Race and the Memory of Evil (2019). Less common is to bring it together with Germany’s confrontation with its militarist past and its transformation into an immigrant nation. It was the confluence of these three ways of attempting to construct Germany anew – making it into a pacific nation, an immigrant nation, and a truthful nation – that allowed Germans to exit the nationalist cage Keetenheuve called Fatherland.

Granted, the metaphor isn’t a perfect one. In the main, Germans didn’t exit that cage by leaving the nation behind them; they didn’t, in the main, become cosmopolitans or Europeans, even if this was the path for some. When, in an opinion poll in 2001, Germans were asked to choose between identities, the overwhelming number (c75 per cent) picked ‘German’ over ‘European’ or ‘citizen of the world’ as their principal identifier. Germans, these polls suggest, exited the cage by becoming better Germans. What they tried to leave behind was not their nation but their nationalism. Certainly, there is more of the path to walk down. But that many postwar Germans have even begun to take this path ‘less travelled by … has made all the difference’, to borrow from the poet Robert Frost – and not just for Germany, but for other countries seeking a way out of the nationalist cage.