Consuming opium was once a tolerated vice in Southeast Asia. Nowhere was it universally accepted, but it was also not an absolute evil. Sovereigns banned opium, yet royal troops could receive supplies deemed necessary for morale. Religious authorities proscribed the drug, yet a Buddhist monk in Burma could legitimately use it during tattooing rituals. Opium was a ‘sinister friend’ to the Javanese that could at once drag them into penury, and ease the pain and discomforts of life’s necessary labours. Across the Malay archipelago, village elders frowned upon opium smokers as lazy and apathetic even as their communities shared opium pipes in private homes, at public gatherings to enjoy what one European visitor called ‘such a tickling in [the] Blood, such a languishing delight … that it justly might be termed a Pleasure too great for human Nature to support’.

For centuries, opium’s place in everyday life across Southeast Asia had been shaped through a variety of political, legal, religious and cultural practices, which also established boundaries of transgression in fluid ways. Smoking opium was a sumptuary practice with many possible meanings – from an analgesic, curative medicine and aphrodisiac to a depraved habit and immoral indulgence. The habit was not necessarily widespread but still far-reaching, capable of touching the lives of the powerful and the meek, the pious and the profane, the rich and the poor alike. And opium itself could be ‘at once bountiful and all-devouring, merciful and destructive, sustaining and vengeful’, as the Indian novelist Amitav Ghosh put it in Sea of Poppies (2008).

The Opium Poppy (1776) by Mary Delany. Courtesy the trustees of the British Museum

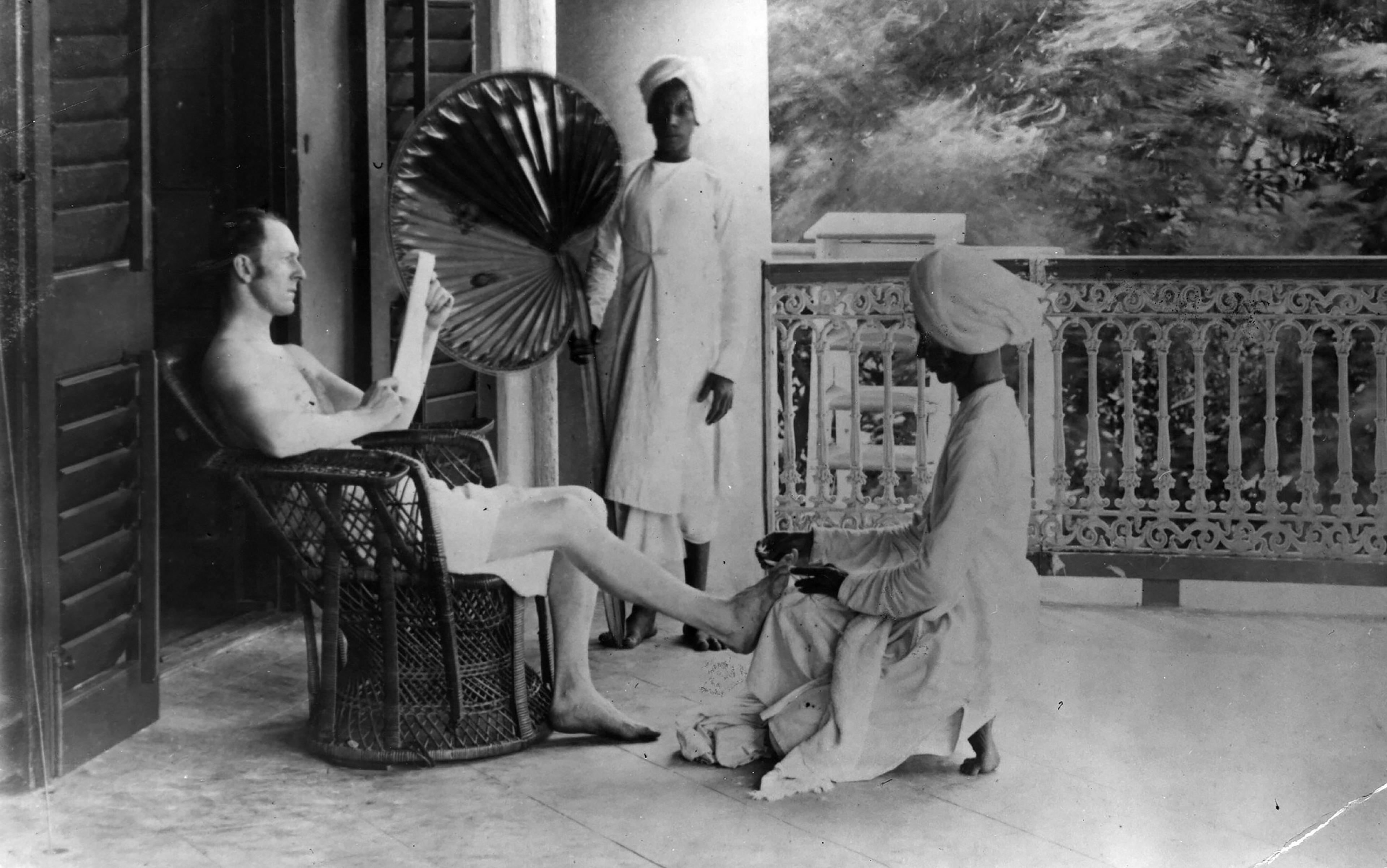

During the 19th century, the vice of opium consumption became a pillar upon which European powers colonising Southeast Asia governed. Empires commercialised the sale of opium and built colonial states that profited enormously from the drug’s popular consumption. In 1819, upon the founding of Singapore as a British colony, its chief administrative officer William Farquhar established an opium tax farm that, by the 1850s, accounted for more than 50 per cent of locally collected revenue. The British used opium revenue to pay the electricity bill for Horsburgh Lighthouse in Singapore and to maintain the prized port’s busy docks and important naval base. In the Philippines, opium helped to sustain the Spanish colonial justice system, providing salaries to all, ‘from the justice of the peace up to the Registrars of Property and Notaries’. From the Dutch tobacco estates of Sumatra and the silver mines of Burma to the tin mines and pepper plantations of Malaya, opium shops operated on-site, providing labourers with easy access to the drug. In Saigon, the French ran an opium manufacturing factory with, as the French doctor Angélo Hesnard described it, ‘vast halls filled with the infamous odour of “boiled chocolate”’ that supplied the drug for everyday consumption across Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos.

However, in the first half of the 20th century, the scent of opium acquired a stench. Opium went from a defensible source of public revenue to a pernicious danger that no respectable empire could justify as a revenue base. Colonial states across Southeast Asia began restricting opium consumption by creating addict registries, rationing schemes and price controls. Opium shopkeepers faced restrictions on whom they could sell their product to, for how much, at what times of the day, while many vendors saw their businesses taken over altogether by the same authorities that had issued sales licences. Hefty penalties attached to violators of new anti-opium regulations that both narrowed and hardened the boundaries of legitimate activity relating to the drug. The many empires dividing the region promised to eventually end opium’s commercial life altogether. Finally, in 1943, the British, Dutch and French officially announced their resolve to completely prohibit opium smoking in their colonies.

Opium’s remarkable reversal of course across Southeast Asia – from fiscal bedrock to banned symbol of disrepute – is not often grasped but it is an important part of modern history. Usually, when people think about empires and opium in Asia, they focus on British India and China, especially their trade relations and the great Opium Wars of 1839-42 and 1856-60. There are stock images of the figure of a portly Qing mandarin humiliated by a European naval officer or an emaciated Chinese opium smoker, languishing in a shadowy San Francisco opium den. In 1928, the English writer Rudyard Kipling described the inner workings of the Ghazipur opium factory, which transformed the vast poppy fields of Benares into ‘the drug, which yields such a splendid income to the Indian government’.

Anchored in these mega-sites of a once-flourishing global opium economy, the orthodox story is of a sweeping change in norms that corrected ‘wrong’ practices – one country foisting an addictive drug upon another; the mass manufacturing of a narcotic for government gain. We credit moral crusaders, in particular religiously inspired social reformers and activists who convinced the mighty powers-that-be that opium presented an unacceptable moral scourge. And so, in this telling, the world came to better understand the dangers of opiate addiction, and states cooperated to protect humanity from it.

This familiar story is not so much incorrect as it is incomplete. It tells a triumphant history of opium prohibition that centres on China, India and the decline of their opium trade. But there is another darker history for Southeast Asia, about the tortured way by which colonial states addicted to opium revenue broke the habit. Unlike in India under British rule, Southeast Asia was divided by multiple European empires that taxed and profited from the drug’s consumption among local inhabitants rather than opium’s cultivation, production and export. Unlike in China, the mass popularisation of opium occurred in Southeast Asia under foreign rule. The British, the Dutch, the French and the Spanish alike once justified the commercialised life of opium as serving the interests of indigenous populations, as well as Chinese and Indian migrants and their diaspora communities that helped to build and sustain major colonial industries. For the same powers to now ban the drug entailed reversing the economic foundations of colonial governance overseas. How was this possible?

The key protagonists were workaday bureaucrats stationed in Southeast Asia to run the colonies. By way of doing what mid- and low-level administrators do on an everyday basis – implementing policies, keeping records – they reconfigured the inner workings of opium-entangled colonial states. They drafted schemes to replace the riches of opium taxes in budgets while renaming extant entries in ledgers that referred to opium revenue under general categories of excise taxation. They saw opium smoking as suspect behaviour, while registering people as habitual opium consumers, addicts and eventually criminals. They cancelled agreements with businessmen who had imported opium to supply opium factories, and reissued formal contracts for only a select few, while redefining the rest as illegal traders and smugglers. Such small acts of administrative adjustment were the stuff of a large and slow process of opium prohibition.

It is easy to think lightly of on-the-ground officials and their pedestrian work. It might seem as if they were simply implementing directives from metropolitan Europe or just giving concrete form to the abstract resolve of politicians, senior bureaucrats, diplomats and other higher-ups of empire. But this would be a serious mistake. My research shows how local administrators wielded strong discretionary powers that affected the course of history. Working in the administrative archives of the British and French opium monopolies for colonies that are today’s Cambodia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Singapore and Vietnam, I discovered how these bureaucrats designed anti-opium reforms that outpaced and went deeper than what their superiors, moral crusaders or international community sought. These state actors developed commonplace philosophies about how a state should be run, the legitimacy of its authority, as well as the nature of vice and its proper regulation. They drew on their accumulated administrative knowledge and their own opinions about the proper way to manage opium consumption as a peculiar vice among others.

At the stroke of Smeaton’s pen, the colony’s number of people affected by opium increased by fivefold

Donald Mackenzie Smeaton was a British bureaucrat stationed in Burma since 1879. He calculated that nearly 11 per cent of Lower Burma’s population were harmed by opium smoking. Smeaton used the term ‘morally wrecked’ to categorise such colonial subjects. This turn of phrase, and Smeaton’s quantitative estimates of the toll of opium on lives, would play a powerful role in guiding the British colonial state toward banning popular opium consumption in 1894, the first anti-opium reform of its kind in a European colony in Southeast Asia.

Smeaton was a careful administrator. He began by calculating the number of opium users in his jurisdiction, using two sources: statistical records from Burma’s jails since the 1870s and a colony-wide survey of opium consumers. Based on these official records, Smeaton estimated that there were around 85,000 adult Burmese males who used opium, which was less than 1 per cent of the total enumerated population. He reasoned that this figure undercounted users because the survey would capture only the ‘most notorious consumers’. Smeaton was a collegial official, attentive to what his fellow administrators thought. The commissioner of Arakan had ‘long and intimate acquaintance with the province and people [of Burma] and who [had] taken pains in the inquiry’. He was ‘convinced that the opium consuming population is much higher’. Smeaton agreed.

So Smeaton doubled his estimate: the share of Burma’s population that regularly consumed opium became 2 per cent.

Next, Smeaton wanted to understand the impact of opium consumption. He assumed that the 85,000 Burmese opium users were the fathers of 85,000 families, upon consulting census reports that gave the average size of a Burmese family at around five people. At the stroke of Smeaton’s pen, the colony’s number of people affected by opium increased by around fivefold.

Smeaton’s estimates were not completely arbitrary. In his own words: ‘I took the greatest pains to consult those and others, who had large experience of the people, and who were in the confidence of the priests and laymen,’ in addition to the reports of other British administrators. Similar problems were being reported in many different places:

Age 37, was a strong man 13 years ago; then took to opium and is now unfit for ordinary labour. He is supported by his parents and does nothing.

Another:

formerly a clerk to the Myothugyi [township chief] … two years after he had taken opium, he could not perform his duties, so he was discharged … and supported by his wife. He became a beggar and died of opium dysentery after 10 years and was buried at the expense of the villagers.

Others lost their jobs, and one

then associated with thieves and committed theft himself. He was often imprisoned and died of opium dysentery when he was 50 years old. He was buried by the charity of villagers.

Smeaton saw a pattern, a downward spiral following opium consumption among the Burmese. Opium hurt users’ families, loved ones, neighbours and communities.

The methodical bureaucrat Smeaton was also a committed empiricist. He recognised that such indirect effects were not direct evidence of harm. Although the richly descriptive observations that he favoured conveyed a sense of the injuries caused by opium consumption, they used vague terms. For instance, the jail of Akyab reported the colony’s largest number of opium-smoking inmates, and gave a long list of attributes defining convicted criminals, including ‘emaciation’, ‘debility’, ‘impotency’ and ‘wandering thoughts’. Town administrators categorised Burmese opium consumers based on ‘deleterious effects’, ‘suffering physically or mentally’ or ‘taken to crime’ and ‘reputed to be a thief’. Such messy language could hardly be used neatly in the official record.

So Smeaton decided to tame the unwieldy details under a general label of ‘morally wrecked’. He equated opium consumption among Burmese as harm done to families or soon to happen. He arrived at the final step of his assessment, concluding that at least ‘11 per cent of the families in Burma have fathers who are habitual opium-smokers or opium-eaters’. The estimate appeared in his ‘Note by the Financial Commissioner on the Extent to which Opium is Consumed in Burma and the Effects of the Drug on the People’ (1891).

Words have power. Numbers help to persuade. Very soon, Smeaton’s calculations became an official fact about colonial reality. The British government of India acknowledged, as evidence of extraordinary circumstances in Burma, that at least one in 10 colonial subjects were injured by opium consumption. This enabled, through provincial adjustments to the all-India Opium Act (1878), the first official ban on popular consumption in Southeast Asia under European rule. Smeaton’s phrase ‘morally wrecked’ served as a formal heading in statistical tables enumerating and classifying Burmese opium consumers. The language further captured the imagination of higher bureaucrats and politicians of the British empire as well as the media, activists and social reformers. Some, such as the Gladstonian Liberal MP and Quaker Joshua Rowntree, celebrated it as an expert’s authoritative statement about opium’s dangers for non-European people. Rowntree cited Smeaton’s perspective in his popular books Opium Habit in the East (1895) and The Imperial Drug Trade (1905).

In Burma, he insisted, ‘crime is the effect of the consumption of opium, and not the cause’

Others disagreed. ‘Do you not think that the heading “Physically or morally wrecked” is sensational?’ Smeaton was asked on 19 December 1893 by a Royal Commission on Opium, which correctly anticipated that Smeaton’s note, ‘when it comes into the possession of a certain part of the English public, will be much used and much relied upon’. And was he not making the ‘most extravagant assumption’ that opium caused crime or tendencies for crime? Perhaps, suggested the commission, it was the other way around, with criminals being more prone to using opium, and Burma simply experiencing higher crime rates in general?

Smeaton responded without demur: ‘What you call the effect is the cause.’ In Burma, he insisted, ‘crime is the effect of the consumption of opium, and not the cause’.

What can we make of this man? As an individual, Smeaton was a person of neither ineptness nor malice. Quite the opposite. At the time, he was financial commissioner of Burma, had served in the Indian Civil Service for more than 20 years, later served as a member of the Legislative Council of Burma, and after retirement became an MP for Stirlingshire in Scotland. Smeaton was a critic of British opium policy in Asia, a self-avowed member of a righteous sort of ‘battalion of opposition’. He believed he had helped to protect the people of Burma by persuading the colony’s chief commissioner to ban opium. In a speech before the Society for the Suppression of the Opium Trade, Smeaton later explained:

When Sir A Mackenzie received my report, he [Mackenzie] saw at once there was a necessity for drastic action … He considered the case so strong, the evil so great, and the ruin brought upon the youth of the country so serious that prohibition was necessary.

Yet, there is a certain meanness to what Smeaton did. The label he created identified an entire people as prone to moral wreckage in a way that relied on racism. It essentialised the Burmese by describing opium consumption as leading to abject vulnerability and suffering in ways that didn’t apply to Europeans. The practice could certainly be harmful, but hardly uniquely so for Burmese men. Moreover, ‘moral wreckage’ was not the only way to look at any and everyone who used opium, let alone describe how the drug affected their bodies and minds.

Historians of Southeast Asia disagree about when and how opium smoking began and if it was a popular practice before European rule. Yet, most recognise that opium already had a complicated place in people’s everyday lives. It was central to ‘coolie’ labour migration from China since the late-17th century, which initially aimed at producing tin, gold, pepper and sugar for the Chinese market, and eventually contributed to the development of Chinese capitalism in Southeast Asia. Important studies on the kongsi (or working collectives) in Borneo, Riau and Johor underscore how opium was a luxury commodity, a painkiller and a means of extracting labour value all at once. Also, in literary texts and community folk wisdom, opium consumption had long met with ambivalence. In his book Opium to Java (1990), the historian James Rush notes how:

The dichotomy of attitudes in Suluk Gatoloco and Wulang Reh – between a celebration of opium’s pleasures and a recognition of it pernicious consequences – also found expression at a popular level. In shadow puppet plays, clowns wore opium pipes in place of swords and indulged in opium-related irreverences, sometimes referring to opium personally as Mbok Lara Ireng, Woman Black Sickness.

Smoking opium could be an occasional indulgence but also impossibly addictive, a cause for scorn from others and of disrepute, but also a reason for status envy.

But through a bureaucrat’s act of identification and description, this wide range of human experience with opium in Southeast Asia narrowed and calcified into something tragic and terrible. A once-tolerated vice became an official crime. Smeaton explained exactly how: ‘Petty crime, petty thefts from his own father’s or mother’s or mother-in-law’s house; reaping crops from other people’s paddy fields, and doing things among his own people.’ He professed privileged insight because opium-induced moral wreckage in Burma was such a petty sort of nonviolent crime that it often evaded the criminal courts and was invisible to those outside the colony. But, Smeaton assured the Royal Commission on Opium, this was the reality on the ground and ‘the kind of offence that the Burmans understand when they call the subject “morally wrecked”’. The local term, he added, was beinsa. Smeaton was not an arrogant man, but the administrative work he did presumed special knowledge about the real lives of others and an ability to speak for them.

Such figures as Smeaton pose conundrums for how we understand the past and, more generally, judge the conduct of bureaucrats essential to the running of states and empires.

At one level, mid- and low-level administrators who acted, spoke and wrote like Smeaton represent essential cogs in state and imperial machines. They helped to uphold double standards for colonised Asian populations that couldn’t be implemented in metropolitan Europe. These different governing practices brought social results that were then used as the very evidence or proof of racial difference and colonial inferiority. Britain, for example, had limited the sale of opium under the Pharmacy Act of 1868, followed by prohibition under the Defence of the Realm Act (40B) of 1916 and the Dangerous Drugs Act of 1920. But such national laws didn’t have imperial reach. Similarly, in France, landmark anti-opium decrees carved out exceptions for Indochina where, as the minister of the colonies acknowledged in 1916, their ‘strict and immediate application … would bring in the balance of [the] budget a disturbance which must be taken into account’. It is easy to think in terms of blame, culpability and cautious counterfactuals. How much responsibility did administrators who ‘merely’ made discriminatory regimes work bear? How volitional, how deliberate was their conduct? How much does intent matter? And would the larger gears of imperial power have moved differently had administrators acted differently?

Inside bureaucracies, there are seemingly minor administrators who wield enormous discretionary power

At another level, bureaucrats are products of their own times. During the 1890s, when Smeaton was calculating the ‘morally wrecked’ in Burma, scientific knowledge about opium’s addictive properties was still evolving. At this point, the German pharmaceutical company Bayer was starting to sell the highly addictive synthetic diacetylmorphine commercially, under its trademark name of heroin. International drug-control regimes that we recognise today, with the ‘right’ approach to limiting legitimate opium to medical use, had yet to be fashioned. The meeting of the Shanghai Opium Commission in 1909 and the International Opium Convention at the Hague in 1912 – landmark events for multilateral cooperation against commercial opium – wouldn’t happen for another decade. It is easy to recognise that what we now see as the dangers and immorality of drugs were not obvious to people in the past, and we can ask: knowing what they knew, were their decisions and actions reasonable, were they moral? What were foreseeable futures then, and how much of our own prejudices, our benefit of hindsight, partial recall and incomplete knowledge of their world, mar (or shape) our assessments of choices?

Harder questions come from grappling with our own feelings about what bureaucrats do. For there is something familiar about the pen that Smeaton held, his ways of reasoning through imperfect numbers and constructing a reality that did inevitable injustice to the nuanced lives of those it purported to describe. This is the nitty-gritty stuff behind what the political scientist James Scott in 1998 called ‘seeing like a state’. Inside bureaucracies, colonial and otherwise, there are seemingly minor administrators who wield enormous discretionary power – over the production of words, numbers, truths and mistruths that appear in government records. They can also construct historic facts – such as the vice of opium smoking in Southeast Asia as a crime – that become cited officially, available for public consumption, manipulation and instruments of knowledge-wars.

Discretionary power within bureaucracies usually has a negative connotation, from misleading superiors and shirking responsibilities, to rent-seeking behaviour and outright corruption. But the discretion that administrators wield on a day-to-day basis is also often a form of localised problem-solving aimed at easing small tensions, filling in gaps of information, accommodating sudden crises in order to keep the state running. Routinised tasks of recordkeeping and paperwork can become interpretive acts, as actors puzzle over their objects of regulation and self-define why their work is meaningful, necessary and indeed valuable. For, to cite the poet Samuel Coleridge, even ‘the meanest of men has his theory’ and must envision his own just reasons for action.

The political theorist Bernardo Zacka shows how, in democratic states, street-level bureaucrats develop moral dispositions while working in difficult environments with conflicting normative demands. In his book When the State Meets the Street (2017), Zacka writes:

As frontline workers in the public services, they are condemned to being front-row witnesses to some of society’s most pressing problems without being equipped with the resources or authority necessary to tackle these problems in any definitive way.

Ethical dimensions of administrative work are harder to see in settings, such as a colonial state, that formally institutionalise racial, ethnic and class-based inequalities. Yet the more we look at the work of the individuals who perform daily state administration, the more we are forced to reckon with a form of moral agency that makes sense in an uncomfortable way. The better we understand the intractable problems they struggle to solve, the more we end up confronting the ingenuity and creativity that bureaucrats can wield.

But why is this unwelcome? What is so uncomfortable about finding something ‘good’ in ‘bad’ actors? And does thinking historically sometimes help us avoid figuring out why exactly we feel how we do about agents of the state? These are blunt versions of difficult questions about how to judge others and the uses of history. It is easy to either condemn or condone. It is also tempting to withdraw altogether, to either avoid the personal discomfort of strong emotions or the crude seductions of moral relativism. But there is a wide grey area in between. This space is unsettling, and indeed difficult terrain in which to think and feel. Yet, compared with the alternatives, surely the more thoughtful approach is to encourage suspicion of our own convictions before venturing to judge what others do. It is the kind of empathy with which we might hope that historians of the future will judge us and our role in our own difficult times.