On 12 May 2010, the former pope Benedict XVI addressed a gathering at the Cultural Center of Belém in Lisbon. The building, though modern, evokes nostalgia for the Portuguese empire, which spanned six centuries, from the capture of Ceuta in 1415 to the handover of Macau in 1999. Here, the stone caravel of the Padrão dos Descobrimentos (Monument to the Discoveries) projects the heroic image of the Portuguese past, cultivated by António de Oliveira Salazar’s fascist Estado Novo rule, over the waters of the Tejo river. Nearby, in the Jéronimos Monastery, Vasco da Gama and the bard of Portugal’s empire, Luís de Camões, lie side by side. While da Gama’s legacy is immortalised in the adjoining Praça do Império (Empire Square), the warning from Camões regarding imperial ambition as that ‘canny consumer/of treasures, of kingdoms and empires’ seems largely forgotten in this corner of Portugal’s capital.

Here, Benedict XVI reminded his listeners that the Portuguese have been ‘deeply marked by the millenary influence of Christianity and by a sense of global responsibility’. It was the ‘Christian ideal of universality and fraternity’, he claimed, that led to ‘the Discoveries and … the missionary zeal which shared the gift of faith with other peoples’. The missionary impulse, Benedict said, led Portugal, ‘to establish relations with the rest of the world’. Invoking Camões’s words, he exhorted his listeners to draw upon ‘prophetic courage and renewed capacity “to point out new worlds to the world”’.

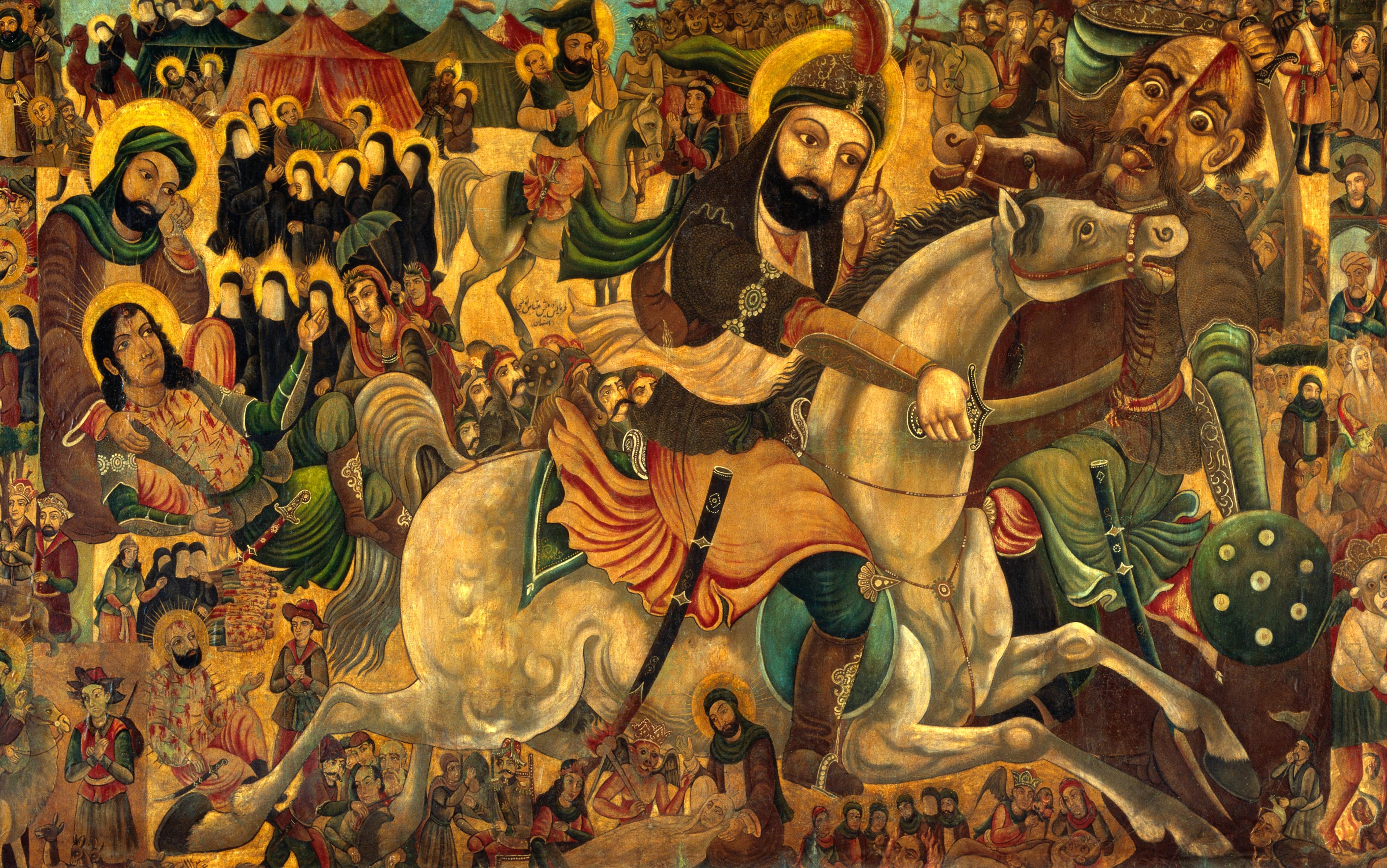

Benedict XVI did not use the word ‘empire’. Earlier, at a gathering of bishops in Brazil, he portrayed the indigenous peoples of Latin America and the Caribbean as ‘knowing and welcoming Christ, the unknown God whom their ancestors were seeking’. The arrival of Christianity in the Americas, Benedict said, ‘did not at any point involve an alienation of the pre-Columbian cultures, nor was it the imposition of a foreign culture’. To Benedict, Christianity in the Americas came not with genocide but with a happy cultural synthesis. Humberto Cholango, president of the confederation of the Kichwa peoples of Ecuador, responded scathingly by affirming the vitality of Catholicism in contemporary indigenous culture, but also reminding Benedict XVI that the sword of empire had long been one of the most effective weapons in the Church’s arsenal.

Yet, if Benedict XVI chose to speak of the Church without the empire, many scholars speak of empire without the Church. Certainly, the Church was never a mere handmaiden to empire. Especially after Urban VIII’s reinvention of the papacy from 1623 onward, Rome was a power independent of the Catholic monarchies in global politics. Moreover, indigenous people around the world adopted Christianity for their own reasons, ranging from the political to the cosmological. At the same time, the religious imagination shaped European imperial thinking – an imagination that Benedict XVI exemplified in his speech at Belém.

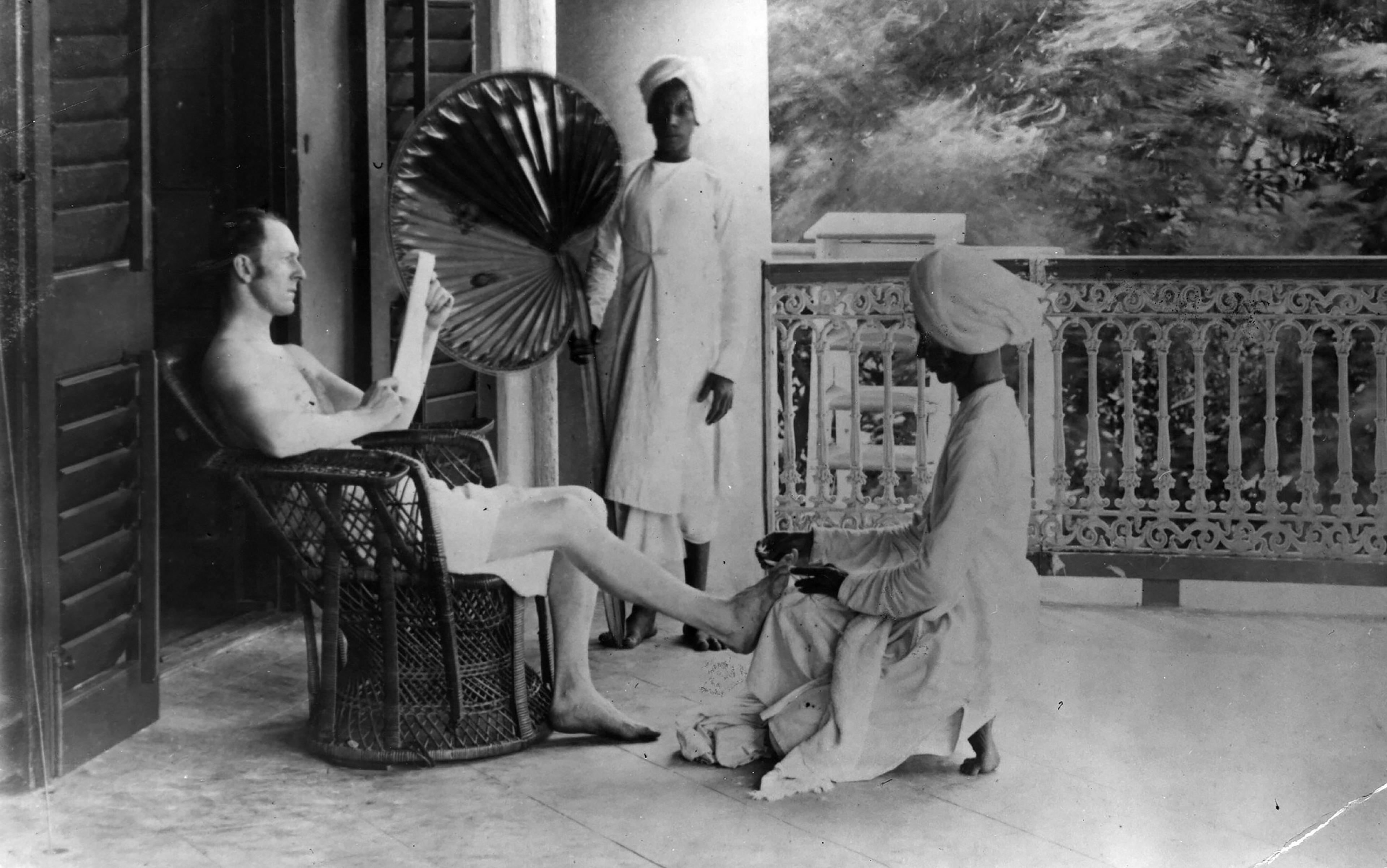

In the 16th and 17th centuries, European presence in, say, the backlands of Brazil or the shores of India did not much resemble the grandiose discourse of European empire. Missionaries, in particular, failed or found themselves thwarted all the time. Indigenous people proved uninterested in their message, often responding with hostility and violence or, at best, adapting Christian theology to their own ends. Imperial agents were less concerned with spreading Christianity than with securing and mollifying local allies in the name of the king – or even just to line their own pockets. Yet, despite repeated failures and disappointments, missionaries – and especially the Jesuits – built and passed on a blueprint of imperial thinking. Their schema of classifying the peoples of the world in civilisational hierarchies in which the European occupies the top echelon, and a sacralising, triumphant vision of empire, remains with us today. It is not a way of thinking that calls attention to either the violence or the many failures of European empire.

How did this gap between the reality of empire and its grandiose discourse emerge? One answer lies in the way that missionaries communicated with Europe about their experience. Ignatius of Loyola implored missionaries to write only of success in public letters known as cartas particulares. These letters, full of edifying stories of pious indigenous converts and the rewarding labour of missionary work, circulated widely, particularly among elites. Europeans read only of the supposed triumphs of imperial evangelism. But the frustrations and failures of imperial experience were legion. Among themselves, Jesuits complained, discussed and strategised over them constantly. These private conversations in hijuelas, or private letters, circulated only within the order, not for public eyes.

For example, though Francisco Xavier is remembered today as the wandering saint, his letters reveal failure after bitter failure across Asia. Originally assigned to the Parava fishermen of the Tamil coast who had converted en masse in return for Portuguese protection against the depredations of a rival fishing community, Xavier’s initial optimism for his mission quickly withered. When he arrived in India in 1542, he fully expected the pious support of the Portuguese empire in his work and a pliant population ready to embrace Christ. The reality was very different.

To his fellow Jesuits, Xavier wrote of an apocalyptic landscape of belligerent cannibals and hell-beasts

When Xavier negotiated a delicate deal with the king of Kollam to settle the Parava in his lands away from the depredations of invading forces from the Telugu country, the Portuguese captain of the Fishery Coast stubbornly continued to supply war-horses to rival kings, thus thwarting Xavier’s efforts. When Xavier struck up a friendship with a learned Brahmin whom he fully expected to convert, he proved a bitter disappointment: his friend offered only to ‘convert’ in secret while maintaining his Brahminical practices and social position. Eventually, Xavier wrote to his companion Francisco Mansilhas of his wish to abandon his mission and ‘to go where I desire, to the land of the Preste, where so much service can be done for God our Lord without having someone persecute us, it would not be much to take a [skiff] here in Manapar and take myself off to India without delay.’ The India of Prester John, the mythical king that medieval Europeans believed ruled a Christian kingdom in the east, was not the India that Xavier found in southern India. He longed to leave the harsh realities of the Tamil coast to find instead that legendary king’s utopian lands.

By 1545, Xavier would abandon India for the spice islands of southeast Asia. In his public letters, he extolled the great prospects of his new mission. He told of how the pagans outnumbered the Moors (Europeans believed that pagans were easier to convert than Muslims) and that even the Moors themselves would be easily brought to the light, due to their great ignorance. To his fellow Jesuits, however, Xavier wrote of an infernal, apocalyptic landscape of belligerent cannibals and hell-beasts. So Xavier left the spice islands too, seeking better fortune in Japan. Disappointments there, expressed only in private, would lead him to set sail for China. His public letters, however, urged missionary investment in Japan, a promising land of ‘white people [gemte branqua]’ who were ‘the best that has until now been discovered’. Had he survived, the Chinese too might have proven disappointing – and led Xavier elsewhere.

When his wandering provoked controversy in the Goan mission, starved of his leadership, Xavier wrote to Ignatius to explain his abandonment of India. In his defence, Xavier cited the poor character of Indians, which made them unsuitable subjects for conversion. He also reported that ‘the Portuguese in these parts do not rule over anything but the sea and the villages which are along the seashore; therefore, they are not lords of terra firma but only of the villages where they live.’ The empire that, in Camōes’s poetry, heroes had won through ‘more than human strength/among remote peoples, to proclaim/a New Kingdom’ was, in reality, little more than a network of sea-hugging villages. Yet it was Camōes’s verses of greatness and the image of the Indies as a land of religious promise, from Xavier’s public letters, that would endure in Europe’s imagination. This discourse about the empire would inspire waves of missionaries to flock to the east.

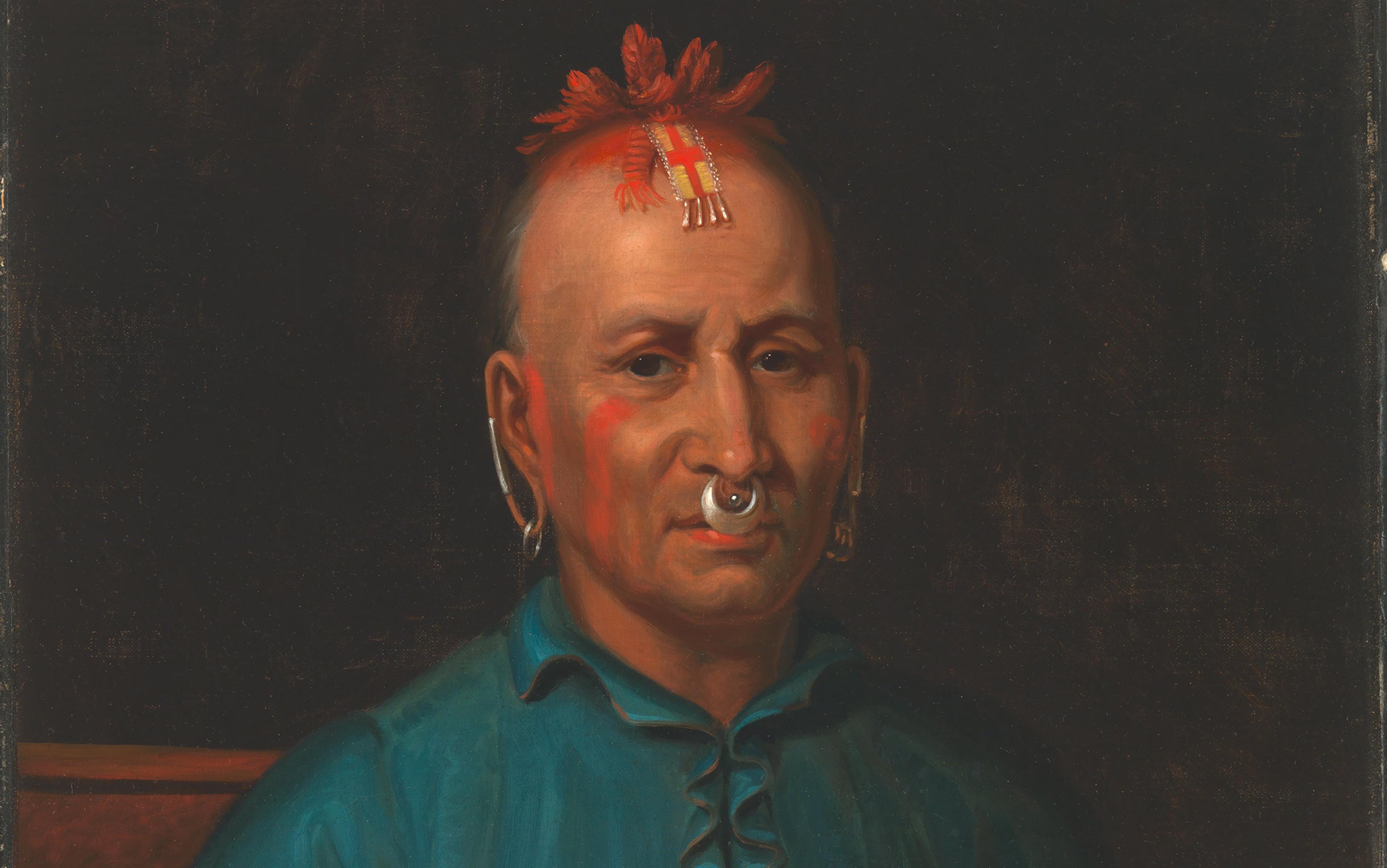

On the other side of the world, the same stark contrast between the reality of empire and the publicity for it stands out. In Piratininga, the indigenous settlement that lies at the foundation of modern São Paulo in Brazil, José de Anchieta was discovering the resilience of Tupí culture, which another Jesuit would memorably describe thus: ‘While their second beatitude is to be singers, the first is to be slayers.’ For Anchieta, Tupí warfare, and its associated rituals of cannibalism and song, presented real obstacles to conversion, and even threatened to corrupt Europeans. In 1555, he recounted how a nearby village celebrated a victory in battle with ‘great festivity’, conducting their ‘miserable ceremonies of the death of enemies’ before the Portuguese, who ‘far from impeding or reprimanding them … attended the spectacle and praised it’. The Europeans’ approbation, Anchieta reported, in turn ‘very much excited’ the catechumens of Piratininga, who then decided to also leave for war.

The participation of catechumens in pagan warfare was a resounding failure for the mission. In his letters to Europe, Anchieta disguised the setback. He stressed, for example, that they did not participate in a precombat ritual offering of a sacrifice to a shaman. Instead, when asked ‘if they wished to give credit to these lies’, the catechumens responded that they did not, and were confident that ‘they would achieve greater victory than those with their filthy sacrifices’. Anchieta wrote of how the catechumens observed Christian customs in the aftermath of battle, taking care to bury the dead, instead of disinterring the corpses and carrying them off ‘to eat’. Yet, in reality, the Jesuit missionaries resorted to frank coercion to prevent the villagers from sacrificing and eating two captives. Anchieta depicted Piratininga as a blossoming Christian mission, but the reality was of Tupí independence and cosmological resilience.

Anchieta’s misrepresentations of Tupí war as Christian crusade also emerged in a letter describing another conflict. In this one, the Tupiniquim converts of Piratininga participated in a joint campaign with the Portuguese in 1561 against their enemies, the coastal Tupinambá Tamoios. While the Portuguese governor Mem de Sá’s campaign of 1560 against the France Antarctique colony had struck a significant blow against the imperial pretensions of the French in Brazil, their Tamoio allies remained formidable. Anchieta recounted that a priest and a brother interpreter accompanied the war party ‘to carry forward the flag of the cross’. As befitting Christian warriors, the men had confessed and taken communion before reaching the enemy, ‘making these untamed and frightening woods a church’. For European readers, Anchieta painted an image of the bellicose villagers of Piratininga as Christian crusaders, instead of Tupí warriors. Yet, the truth is that the Tupi were continuing a conflict with the Tamoio that long predated the arrival of the Christian shamans in Piratininga.

The indigenous of Brazil sat on the bottom rung of humanity; their culture was an unfit vessel for Christianity

Pope Benedict XVI claimed that ‘It was only a question of time before Europe would expand toward America and in part toward Asia, continents that were lacking in great cultural protagonists.’ But his fateful view was not shared by the cultural protagonists themselves. Time and again, necessity forced the Jesuits, and other Europeans in Asia and America, to adapt to the cultures they encountered. The phenomena became known as Jesuit accommodatio, their practice of modifying the Christian lesson to the capacity and disposition of different peoples and cultures. Accommodatio was a pragmatic weapon of the relatively weak, embraced the world over by Jesuits because imperial arms and Christian authority proved insufficient to compel conversion.

Anchieta would go on to write a remarkable poetic corpus in Tupí, including edifying plays and songs for indigenous converts. He drew on a profound understanding of their culture, borne of his long years and missionary experience in Brazil. Yet, his successors in Brazil would not pursue such cultural accommodation. The consolidation of the Portuguese power monopoly on the Brazilian coast against French rivals and indigenous enemies led to more coercive methods. Indeed, the Jesuits secured a monopoly from the Portuguese crown, in part as a reward for their assistance in quelling the French, to ‘descend’ indigenous peoples from the backlands and confine them in mission villages known as aldeias. In these aldeias, the missionaries could control every aspect of indigenous life, from the cosmological to the material. Cultural accommodation to indigenous people became unnecessary.

By the end of the 16th century, an intellectual consensus emerged among the Jesuits that Brazil’s indigenous peoples and similar societies without writing or hierarchical states occupied the bottom rung of a civilisational ladder. José de Acosta’s evangelical handbook De Procuranda Indorum Salute, or ‘On How to Bring About the Salvation of the Indians’ (written in 1577 in Lima, published in Seville in 1588, and republished in Salamanca in 1588 and Cologne in 1596), announced the change. Subsequent editions came prefaced with the first two books of De Natura Novi Orbis, Acosta’s moral history of the peoples of the New World. The work came to be used as a textbook by the Jesuits not only in the Americas, but also in Europe, North Africa and in the Asian missions. In Acosta’s schema of peoples, the indigenous of Brazil sat on the bottom rung of humanity; their culture was an unfit vessel for Christianity. To evangelise them, the indigenous way of life could not be preserved. By contrast, and consistent with Xavier’s views, Acosta deemed the Chinese and Japanese closest to ‘right reason’ – that is, European ideas of civilisation. For the project of evangelisation, therefore, Chinese and Japanese cultures could be accommodated. It is not incidental that the Catholic empires could subjugate neither the Chinese nor the Japanese – accommodatio was the missionaries’ only option.

The European schema of human cultures emerged from the structure of the Society of Jesus. It was a tightly knit, diasporic order emphasising written communication between its members. Jesuit missionaries shared the knowledge they gained in the mission, including practical strategies for engaging indigenous peoples, and circulated it to members throughout the world. The flow of information around the globe helped Acosta develop his hierarchy of peoples, and gave him additional motive to do so.

The underlying idea of the Jesuit endeavour of classification was that peoples could be organised into a cultural hierarchy with the European, as fully human, at the top. This basic project remains one of the most pernicious legacies of empire, surviving well past the era of colonial rule itself. The knowledge that Jesuits gained from missions helped to shape the logic of global empire. The gap between what the order presented to its European audience and what it kept to itself was significant – and helped to maintain the fiction of this schema. Acosta’s hierarchy of peoples was widely circulated and taught; Anchieta’s Tupí writings, in which one hears echoes of the rich poetry of Brazil’s indigenous peoples, were not.

The gap between the reality of the colonies and the European perception could grate upon missionaries. In 1638, after the Dutch barracks erected in front of the church of St Anthony during the Dutch West India Company’s campaign in the state of Bahia in Brazil were uprooted, the great Jesuit António Vieira gave a sermon. This Portuguese victory, like other events of significance to the colony that lacked a printing press, remained unknown in Europe. Keenly aware that ‘what everybody saw’ in Brazil remained unknown in Europe, Vieira’s sermon presented a passionate indictment of the colonial system. The colony, Vieira said, received neither adequate support nor recognition for its efforts to preserve Brazil for Portugal. Royal officials, ‘the successors of Pilates in the world’, hid Brazil’s true condition from their masters in Lisbon. He denounced the rank exploitation of the colony. ‘In its time,’ Vieira noted bitterly, ‘Pernambuco gave much; Bahia gave and gives much today and nothing is achieved, because what is taken from Brazil, is taken out of Brazil; what Brazil gives, Portugal takes.’

Vieira resented the European treatment of Brazil because of his missionary vocation. He saw his mission not as a peripheral colony, but as a vital theatre of divine drama – in which imperial politics played a role. For him, the Portuguese willingness to cede Brazilian territory to their Dutch Protestant rivals was unconscionable – it meant abandoning the dominion of the Catholic Church.

The grandiosity of imperial discourse not only masks the reality of empire; it shores up political support for it

As the Portuguese empire crumbled in the 17th century, Vieira and other colonial missionaries turned to theology for consolation. They developed a theory in which the Portuguese would fulfil the prophet Daniel’s promise: ‘In the time of those kings, the God of heaven will set up a kingdom that will never be destroyed, nor will it be left to another people. It will crush all those kingdoms and bring them to an end, but it will itself endure forever.’ Blending biblical prophecy and Portuguese history, the Portuguese Jesuits shared this prophecy among their ranks, from the backwaters of Kerala to the Amazonian jungle. Vieira and other Portuguese Jesuits worked hard to save the empire. They even countenanced – as part of their religious vocation – such profane activities as the solicitation of money from the Portuguese Jewish diaspora in order to fund imperial soldiers. Their writings and activities helped to sacralise empire, presenting it as part of cosmological conflict. This grandiose vision of empire can still be seen in the Praça do Império in Lisbon today.

Once you see the difference between ostentatious imperial discourse and miserable colonial reality, you realise that this grandiose vision of empire has never gone away. It continues to structure our world. In August 2007, the then US president George W Bush addressed the national convention of Veterans of Foreign Wars. Casting the Iraq war as part of the expansion of what Ronald Reagan had called the American ‘empire of liberty’, Bush beseeched Americans to stay the course. Curiously, he did so by focusing on Vietnam. According to Bush, Vietnam was not an example of murderous imperial folly; rather, its lesson was the danger of defeatism. The price of withdrawal from Vietnam, Bush claimed, was new enemies: he cited Osama bin Laden’s declaration in 2001 that ‘the American people had risen against their government’s war in Vietnam. And they must do the same today.’ Thus, withdrawing from Iraq would be to repeat the real mistake of Vietnam – opposition to war.

Bush’s speech came after the release of photographs of horrific abuses at Abu Ghraib prison. The pictures showed it was the self-styled proponents of civilisation who had descended into barbarism. Amid rising criticism – for the torture at Abu Ghraib, for growing casualties, for continuing political instability in Iraq – Bush turned to religion and history to defend the war. He urged listeners not to doubt US imperial destiny: ‘The greatest weapon in the arsenal of democracy is the desire for liberty written into the human heart by our Creator. So long as we remain true to our ideals, we will defeat the extremists in Iraq and Afghanistan.’

Imperial triumphalism is not merely rhetorically important: one study has shown that Iraqi insurgent attacks against US military targets spiked in periods following public criticism in the US of the war, resulting in more American casualties even while there were fewer deaths overall. The grandiosity of imperial discourse does not merely mask the reality of empire; it shores up political support for it.

In pushing for continued support of the war, Bush suggested that Americans simply did not know the progress that the US had made in Iraq. A war started on the basis of imperfect information continued in the same vein. The information gap between the metropolis and its imperial outposts helped him – just as it had Jesuits such as Vieira centuries before – to maintain a misrepresentation of empire and its subjects, and to deceive the people on whose political support it depends.