By the late-18th century, Native Americans and European newcomers had lived together in the Americas for nearly 400 years. They had cajoled, fought, killed and hated one another, and Europeans had built colonies on coastal plains and along major river valleys, dispossessing dozens of Indigenous societies – with the crucial help of smallpox and other new deadly diseases that wreaked havoc in Native communities. Yet in 1776, much of the continent was still under Indigenous control. That changed, with shocking rapidity, when the 13 colonies rebelled against British rule and became the United States of America. Liberated from British restrictions on western settlement, self-styled American pioneers began to push beyond the Appalachian Mountains, seeking land and personal independence. That the West belonged to Native nations who had lived there for multiple generations mattered little to them.

In April 1832, the US president Andrew Jackson refused to enforce the ruling of John Marshall, the chief justice of the US Supreme Court. In Worcester v Georgia, the Marshall Court had decided that Native American nations retained their ‘natural rights as the undisputed possessors of the soil from time immemorial’. Dozens of treaties between the Native nations and the US had sanctioned these rights. Jackson, however, was unmoved. By 1850, in a sustained campaign of ethnic cleansing, 100,000 Indians had been deported west of the Mississippi.

Nearly 200 years after Jackson, on 27 July 2016, the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe filed a lawsuit against the US Army Corps of Engineers over the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline by Energy Transfer Partners (ETP). The pipeline was to pass under the Missouri River north of Bismarck, but the citizens of the capital objected to the risks: pipelines tend to leak and cause environmental degradation and foul drinking water. ETP revised its plans, moving the crossing near the Standing Rock Indian Reservation, where it traversed Native burial sites and risked contaminating the reservation’s water reservoir. ETP bulldozers moved in, ignoring the requests of three US departments to halt construction in a reservation where 47 per cent of the population lives in poverty. The president Barack Obama ordered an environmental review. He vowed to regard the Indians as sovereign nations. Obama’s pledge turned to a dead letter when Donald Trump became US president in 2017. Four days into his presidency, Trump expedited the construction of the pipeline. Immediately, LaDonna Brave Bull Allard, Phyllis Young, Joye Braun and other Sioux women mounted a powerful resistance.

Separated by 185 years, Jackson’s and Trump’s executive interventions both sit at the heart of modern Native American life and history. Both concern sovereignty, a vitally important concept – at once clearcut and elusive – in the world of politics and states. It can be defined as the supreme right of a self-designated body of people to govern itself and control its territory and resources without outside interference – with the crucial caveat that it has to be recognised by others to be effective. Together, through these two actions, we can see something essential about the rights of Native peoples in North America, past and present. Jackson’s and Trump’s assertions of US power over Indigenous peoples call attention to their singular political status as nations within a nation, and they speak to the continuing Indigenous struggle for sovereignty. Treaties are the quintessential tool of international diplomacy, and the US has long practice of making them with the peoples whom it dispossessed from their ancestral lands through brutal and at times genocidal methods.

Emerging from the coalescing American empire and the rapacity of American capitalism, Indian Removal marked the erosion of Indigenous sovereignty east of the Mississippi Valley. It was the Lakota – a Native people that includes the Hunkpapa, the Minneconjou, the Oglala, the Sans Arc, the Sicangu, the Sihasapa and the Two Kettles – who mounted the longest and most comprehensive opposition to US expansionism. The riches promised by King Cotton fuelled a rapid and ruthless implementation of US control and sovereignty in the Black Belt, the part of the American South where geological processes left soils almost perfectly suited for cotton cultivation. In a striking contrast to the forced mass removal of Indigenous Southerners, the Lakota thwarted American imperialism in the West for generations, all the way to the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

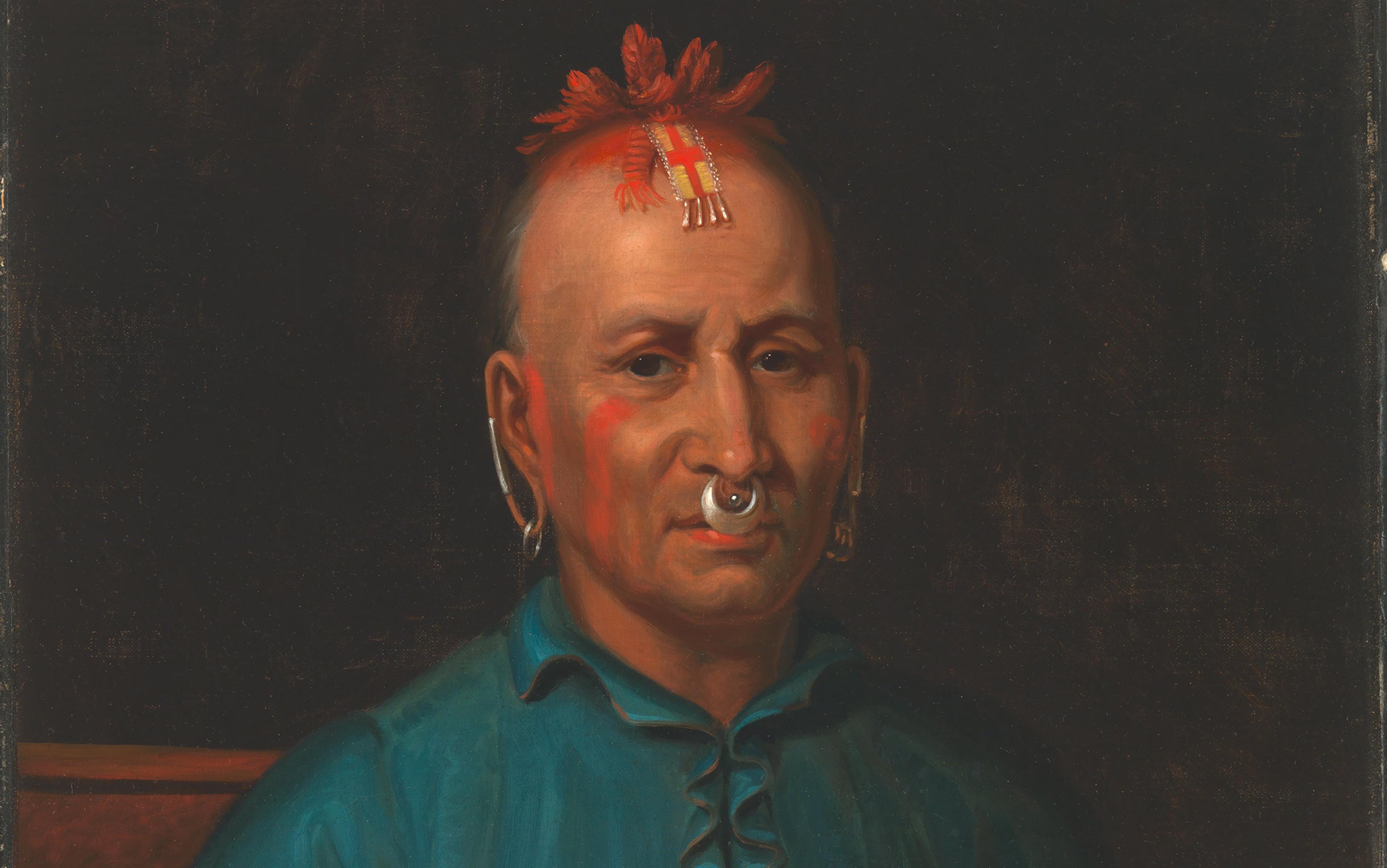

To do so, the Lakota had to reinvent themselves as a formidable warrior society. Crazy Horse, Sitting Bull, Red Cloud and other iconic warrior-leaders embodied that transformation. That history is well-known. What has remained more obscure is how the Lakota mounted a nearly two-centuries-long campaign to preserve Indigenous sovereignty in the face of a US empire that saw them as wards and, when fighting and killing them, as internal enemies.

Military resistance against the US empire was often a blunt affair that demanded direct violent action, materiel and calculated balancing between objectives and acceptable losses. In contrast, the Lakota assertion of sovereignty demanded creativity, flexibility and tenacity. Sovereignty in an Indigenous context can be best understood as a self-identified group’s right and capacity to govern itself against foreign powers that claim superior authority over it. The historian James J Sheehan in 2006 described state-making as ‘the ongoing process of making, unmaking, and revising sovereign claims’. Replace ‘state’ with ‘nation’, and we have a blueprint for the startling history of the generations-long Lakota struggle for sovereignty, which has witnessed numerous reiterations of what Indigenous sovereignty is and how it has been challenged, undercut and reasserted.

On 24 January 1848, about 100 miles north of San Francisco, a carpenter working for the Swiss émigré John Sutter found a yellow substance that turned out to be gold. Nine days later, in Guadalupe Hidalgo near Mexico City, Nicholas Trist and the Mexican envoys signed a treaty that ended the US-Mexico War and transferred about half a million square miles of Mexican soil to the US. Virtually overnight, California became the most prized place on Earth. People rushed in: in 1850 alone, 50,000 overlanders crossed the central plains.

In between the fortuneseekers and the prospect of California gold stood the Lakota, the most populous member of a larger Sioux alliance, Očhéthi Šakówiŋ, or the Seven Council Fires. Since the early 18th century, the Lakota had gradually expanded westward from the Great Lakes region. By 1850, they had grown into a formidable power in the heart of the continent, dominating much of the Great Plains. When the migrants to California carried in deadly diseases, the Lakota began attacking the unauthorised newcomers. American officials grew nervous: the overland trails, the United States’ umbilical cord to distant California, was in danger of being severed.

The mid-19th-century US was a territorial behemoth but a military midget. The Regular Army, reduced after the Mexican War, consisted of roughly 9,000 enlisted men and fewer than 900 officers. The Lakota alone could put 3,000-4,000 warriors on horseback and arm most of them with guns and metal weapons, which they secured from American fur companies that craved their high-quality buffalo robes. The Lakota were but one of the many Plains Indian nations that had experienced a heady expansion of power and reach with the introduction of horses. Military action against these horse nations would have been reckless.

War also seemed unnecessary. The US had just won a stunning victory over the Republic of Mexico. It was a victory that owed much to the Comanches who had raided and pillaged northern Mexico for years, weakening the region for the US invasion. By 1850, the Americans saw the rest of the West as a soft target. The removal of Indigenous Southerners – Indians whom they deemed as at least semi-civilised – had conditioned them to see the continent as a collection of blocks – of land, of people, of wealth – all conquerable and absorbable. The block they now considered, the Great Plains, appeared to them a transitory world inhabited by wild and disorganised hunters whose nomadic way of life was already doomed: the bison herds, the foundation of their economy, seemed to be fading. Many Americans now believed that they enjoyed a special divine fate and that God had ordained for them to take possession of the continent from lesser people in the name of progress and liberty. In 1845, John Louis O’Sullivan, an Irish immigrant and journalist, called it a ‘manifest destiny’.

Guided and blinded by this providential thinking, US policymakers thought that they could be generous. In the spring of 1851, they invited several Plains Indian nations to a grand summit at Fort Laramie in Wyoming, on the North Platte River. There they would negotiate the boundaries and roads through the continental grasslands into California. Some 10,000 Indians arrived, drawn by promises of generous distribution of goods and gifts. The US plan was both ambitious and clearcut: the midcontinent was to be carved up into three sections: a southern reservation, or a ‘colony’, for the Comanche, the Kiowa and the Plains Apache; a middle one for the southern Cheyenne and the southern Arapaho; and a northern one for the Lakota, the Crow, the Assiniboine, the Mandan, the northern Cheyenne and the northern Arapaho. In between the blocks, there were slices of land that would accommodate two overland arteries, the Santa Fe Trail and the Oregon Trail, carrying settlers to the Pacific Coast.

The Lakota commanded the midcontinent like an imperial power, moving over it at will

What the Americans did not realise was that they were facing an Indigenous power that, in the great interior of North America, eclipsed them in military might, political prestige, diplomatic reach and commercial prowess. Lakota spokesmen explained to the US envoys the realities of the steppe. Black Hawk, an Oglala, rejected the carving out of the plains into reservations: ‘You have split the country, and I don’t like it,’ he protested. The Lakota did not understand territory as a block of land, but as spheres where they could move freely and access resources. ‘What we live upon, we hunt for, and we hunt from the Platte to the Arkansas,’ Black Hawk insisted, superimposing a Lakota view of sovereignty over the US one. Bison movements, not fixed boundaries, would define the Lakota range and sovereignty. Black Hawk’s demands contradicted the Americans’ block design for the grasslands almost entirely. The central plains south of the Platte Valley, Black Hawk noted, belonged to the Lakota by the right of conquest – they had ‘whipped’ their rivals out of them – and the Americans caved.

To a significant degree, the resulting treaty represented superior Lakota military power. It recognised the Lakota’s title to 100,000 square miles and – covertly – authorised them to range and hunt wherever necessary. The US had effectively handed over a huge chunk of the mid-continent to an Indigenous nation of some 13,000 people. US delegates had come to Fort Laramie to curb Indigenous sovereignty. Instead, they returned east with their own severely constrained. The US would be reduced to paying for access through lands they considered theirs – $50,000 a year for 50 years.

The Lakota political victory exemplifies what have been called ‘imperfect geographies’ of empire. Thwarted by the Lakota and other nomads, the US government had to consign itself to corridors of control through the vast sea of grass that is the Great Plains. The Lakota commanded the midcontinent like an imperial power, moving over it at will. It was US sovereignty there that was fragmented, contested and full of holes. In reality, US authority there consisted of a few trading posts, garrisons and waystations.

It was the Lakota who controlled access to the West. They allowed civilians to pass through, but not forts or soldiers on their lands. As long as the Americans behaved properly, paying for access and sharing their wares and technology, the Lakota found this layered sovereignty acceptable. But in 1863, gold was discovered in Montana, and the US Army began to build unauthorised military forts along the Bozeman Trail. The Lakota and their Cheyenne and Arapaho allies went to war, defeating the US Army with relative ease. The US War Department ordered the forts closed, and Red Cloud – after whom the war would be named – came to Fort Laramie and made the Americans ‘touch the pen’.

US commissioners and Oglala chiefs meeting for the Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1868. Courtesy the National Anthropological Archives

The resulting Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1868 marked another stage in the evolution of Lakota ideas about power, territory and sovereignty. The Lakota-led Indigenous alliance had defeated a rising industrial giant – an imperial nation-state – in the battlefield, forcing it to negotiate over terms. The resulting treaty created the Great Sioux Reservation and formalised state presence in Lakota lives in the form of government agencies, schools and missionaries. The Lakota, it seemed, had conceded to a plural or limited sovereignty over their domain.

In reality, however, the treaty bolstered Lakota power. Article 2 set apart for ‘absolute and undisturbed use and occupation’ a reservation of more than 48,000 square miles for the Lakota (and some Yanktonai). Article 16 designated the lands north of the North Platte River as ‘unceded Indian territory’. The crucial Article 11 reaffirmed the Lakota’s right ‘to hunt on any lands north of the North Platte, and on the Republican Fork of the Smoky Hill, so long as the buffalo may range thereon and justify the chase’.

By linking the ownership of land and sovereignty to the bison and the hunt, the 1868 treaty seemed to have acknowledged the Lakota practice of delineating territory in terms of access to resources rather than through boundaries. But like many Indigenous-colonial treaties, the Laramie treaty was riddled with inconsistencies. It did not define the northern boundary of the unceded territory, thus unintentionally authorising Lakota expansion deep into the northern plains, and it confirmed Lakota hunting rights in the central plains. Moreover, by linking the Lakota domain to the viability of the hunt, the treaty effectively compelled the Lakota to expand and dispossess other Native people to preserve their sovereignty. Lakota national viability and the migrations of the bison had to overlap, almost perfectly. Controlling the Article 11 hunting domains became a Lakota priority. This could lead only to war.

When the US Indian Office proposed to build a government agency for the Oglala in 1870, the Lakota welcomed it because it facilitated the distribution of treaty goods and rations. Led by Red Cloud, the Oglala insisted that the agencies could not be located within the reservation. They would have to be outside of its boundaries, near the North Platte River. This stipulation baffled US agents. The Oglala, they reported, ‘are extremely sensitive in regard to the slightest encroachment upon their reservation … and have objected even to the establishment of an agency for their own benefit within the limits.’ The agents of the Indian Office had missed the point. Article 11 of the Treaty of Fort Laramie had in effect allocated a massive block of land for the Lakota. They meant to retain sovereignty over it by keeping foreign bodies out of it.

US policymakers had anticipated neither the full implications of Article 11 of the treaty, nor the Lakota commitment to their sovereignty. Yet they welcomed both developments for their own reasons. The Lakota practice of their sovereign rights soon led other Native peoples to seek deals with the US government, because the Lakota soon dominated nearly all of the northern plains, ranging deep into Canada, pushing rival Native hunters out of their way. Desperate to secure American protection, the Shoshone ceded the mineral-rich western portion of their reservation to the US, and the Ute traded their large reservation in the Colorado territory for a much smaller one farther west. In the central plains to the south, the Lakota fought with the Pawnee, the Ponca, the Omaha and the Otoe-Missouria for hunting rights, and the US pressured the weakened groups to move to Indian Territory, thereby completing another crucial stage in its effort to lock the continent’s Natives in a single confined spot.

The Lakota and the Americans were both imperial nations, but they managed to coexist in Western North America for decades not because they were similar but because they were so different. The two nations – the two empires – saw the world, the land and the people on it in incompatible ways. The variance allowed a kind of common ground to arise where they pursued their different visions for themselves. As in many other places where Indigenous and colonial regimes brushed against one another, expedient and creative misunderstandings allowed them to live in peace, even after brutal outbursts of violence. The most useful misunderstandings involved sovereignty and its different meanings for the two people.

The Lakota had to be domesticated. Nearly everything that made them who they are fell under attack

In 1874, when George Custer’s Black Hills Expedition spotted traces of gold in the sand and triggered a massive gold rush, the Lakota changed their views once again. For them, the Black Hills – Pahá Sápa – was their birthplace as a nation. Pahá Sápa was to the Lakota ‘the heart of everything that is’ and therefore inviolate. Custer’s intrusion amounted to an unmitigated assault on the sovereign rights of the Lakota and their Cheyenne and Arapaho allies. Before this violation, the Lakota had accepted, even embraced, layered forms of sovereignty. Now they adopted a distinctly territorial stance and closed the Black Hills to outsiders. To keep prospectors out, the US Army began patrolling the eastern face of the mountain range. But the driving goal was just to buy time for the president Ulysses S Grant to find legal ways to extinguish the Lakota’s title to the gold-laden hills.

It was the collision of the different Lakota-US sovereignty regimes that caused the Great Sioux War of 1876. The US government forced a clash with the most powerful Indigenous nation in North America, which led to the Battle of the Little Bighorn and a devastating US defeat.

The Lakota had won the war but they lost the peace. The bison herds were nearly gone, destabilised and destroyed by railroads, cattle ranches and reckless commercial hunting. Within a year of Custer’s Last Stand, nearly all Lakota lived within the Great Sioux Reservation, boxed in and monitored by government agents. By US logic, there were not supposed to be any sovereign Native nations left within the US, and the Lakota – the killers of Custer – had to be domesticated. Nearly everything that made them who they are fell under attack. Bills and policies poured in from Washington, DC tearing down Lakota sovereignty piece by piece. In the Fall of 1876, a vindictive Congress passed legislation cancelling all government support for the Lakota unless they relinquished all their lands outside the Great Sioux Reservation, including the Black Hills. US government officials sought to suppress the Sun Dance and other ceremonies, and hundreds of Lakota children were forced into off-reservation boarding schools. In 1889, Congress broke the Great Sioux Reservation into five small ones, shattering the unified territorial foundation of Lakota sovereignty.

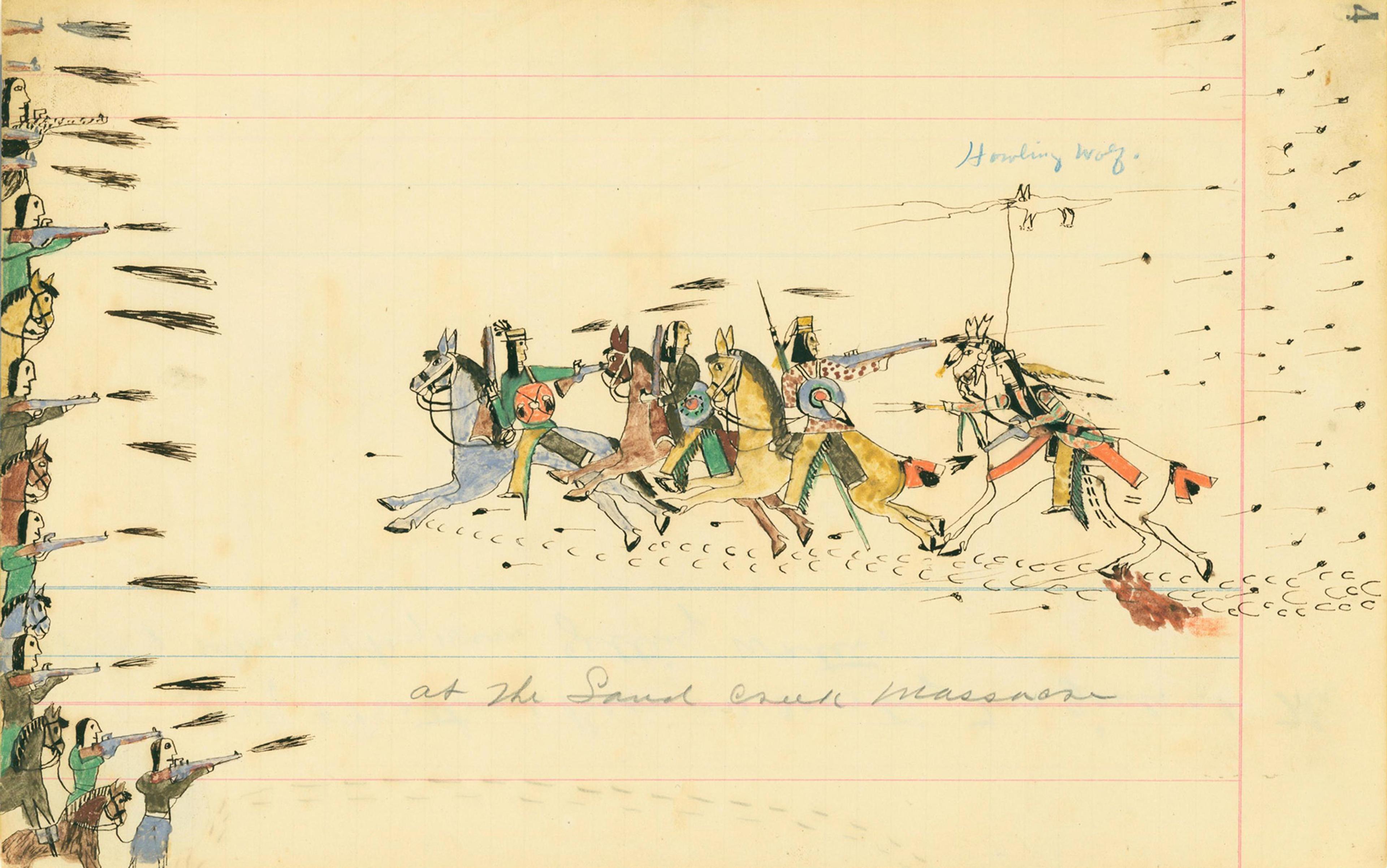

Amid the destruction, inspired by the Paiute holy man Wovoka, Lakota began dancing to bring back dead kin and bison herds and rid the world of white invaders and diseases. This was the Ghost Dance movement. Much of it was symbolic, but its subversive undertones alarmed Indian agents, army officers and settlers who reckoned the movement dangerous. The US government sent the Seventh Cavalry – Custer’s old regiment – to restore order. They escorted the supposedly hostile Indians to Wounded Knee Creek. Army units have long memories. The next day, at least 270 Lakota – children, women and men – were dead.

The Lakota had become a captive people, confined to reservations that sometimes seemed less homelands than prisons. The Indian Office continued to attack their religious traditions, pressure them to dress and talk like white Americans, and use their land according to capitalist principles. By withholding rations, government officials coerced Lakota to lease and sell their land to white farmers and cattle ranchers. Christian churches proliferated, and the Great Spirit became associated with the Christian God.

The Lakota continued to weather violations of their sovereignty. In one particularly symbolic transgression, Americans carved colossal presidential heads (Mt Rushmore) into Six Grandfathers, a spiritually alive section of Pahá Sápa; the initial plan to include Sacagawea, Crazy Horse and Red Cloud was dropped. The 1934 Indian Reorganization Act divided the Oglala and the Sicangu into traditionalist full-bloods, who welcomed the Act as a means of cultural preservation, and progressive mixed-bloods, who denounced it as a forced retrenchment into outmoded ways. The Pick-Sloan plan of 1944 authorised the Army Corps of Engineers to build a 370,000-acre reservoir that deprived Standing Rock Reservation of 200,000 acres of its most valuable land; and in the 1950s, Whiteclay – a minuscule Nebraskan village built on land summarily taken from the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in 1904 – was founded with one function: to sell alcohol into the reservation.

In 1947, the Indian Office became the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), an agency designed to make itself obsolete. The federal government wanted, at long last, to complete the assimilation of the American Indians. Reservations and tribes would be absorbed into the body politic, which in turn would make the BIA itself obsolete. The policy was a disaster: every terminated tribe suffered politically, economically and psychologically, while many of the 100,000 Indians who moved into cities struggled. In the 1960s, the federal government shelved the failed policy. Its primary accomplishment was to deepen Native Americans’ loathing of the BIA, which meant to turn the first Americans into white Americans whether they wanted it or not.

The ‘absolute terror’ that the BIA spread across Indigenous communities helped to foster a powerful sense of pan-Indian solidarity. No Lakota reservations were targeted for termination, but Lakota emerged as key figures in the growing Indian activism of the 1960s. Vine Deloria, Jr, a theologian-scholar from Standing Rock, served as the executive director of the National Congress of American Indians, a new Indigenous rights organisation. Deloria’s leadership coincided with a massive increase in membership. His book Custer Died for Your Sins (1969) was a galvanising manifesto of Indian rights in which he condemned, among other things, the termination policy as a flagrant land-grab. He castigated the federal government’s abysmal record in honouring its more than 400 treaties with Indigenous nations. Alongside the Black Power movement, Deloria argued, there should be a Red Power movement but with a distinct agenda centred on Indigenous sovereignty and continued cultural integrity.

Deloria helped to provide an intellectual foundation for a Native American protest movement that was already gathering force across North America. In Minneapolis, Native activists founded the American Indian Movement (AIM) to help the thousands of Indians that the government’s programmes had pushed into urban slums. Though it quickly expanded into a pan-Indian endeavour, AIM relied deeply on Lakota leadership.

Shots were exchanged, and another massacre at Wounded Knee, now against US citizens, seemed possible

In 1972, white Indian-haters in Gordon, Nebraska captured and murdered Raymond Yellow Thunder, a middle-aged Oglala ranch hand. Authorities failed to mount a proper investigation. AIM brought 1,400 protestors from 80 different tribes to Gordon, engulfing the town in anger. The frightened town officials established an impromptu human rights commission, and a district court jury convicted the killers of manslaughter and false imprisonment.

The AIM leaders had seen what they wanted – genuine fear among white authorities – and they knew they could reach further. They took their movement to the East. In the Fall of 1972, a large pan-Indian delegation, the Trail of Broken Treaties, caravanned to Washington, DC where it occupied the BIA headquarters. The Indians demanded the return of 110 million acres of Native American land and the abolition of the BIA, which they denounced as an instrument of continued colonialism. It was a stunning display of anger and collective action as well as a stinging humiliation to the US government.

The Lakota struggle for sovereignty was becoming nearly synonymous with a broader Indigenous struggle for rights. In the Pine Ridge Reservation, the tribal chairman Dick Wilson, a mixed-blood and a BIA favourite, tried to transfer uranium-rich lands to the Department of the Interior, and used a private militia to neutralise opposition. Pine Ridge was one of the poorest places in the US, with 50 per cent unemployment and collapsing healthcare and education; Wilson’s corruption threatened to plunge the reservation further into the abyss.

In February 1973, AIM decided to move to Pine Ridge. Wilson was ready: 75 federal marshals, all members of an elite rapid-response strike force, had arrived to protect the tribal office building. On the roof of the militarised building stood a .50-calibre machine gun.

It was then and there that AIM realised its vision of itself as a modern-day warrior society, leading the Oglala into a fight against an aggressive foreign government. About 200 Indians, some of them carrying shotguns and hunting rifles, motorcaded to Wounded Knee, a hamlet of roughly 100 residents. It became a standoff. The BIA refused to remove Wilson, and heavily armed FBI agents, National Guard soldiers, and federal marshals sealed off Wounded Knee with roadblocks and armoured personnel carriers. Shots were exchanged, and another massacre at Wounded Knee, now against US citizens, seemed possible. The difference was that all of it was now public: TV crews had arrived.

The Indians at Wounded Knee declared themselves the Independent Oglala Nation. They invoked the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie, which had been negotiated on a nation-to-nation basis, and established the legal foundation of Lakota sovereignty. The Independent Oglala Nation welcomed the assistant attorney general Harlington Wood like a foreign dignitary: two young mounted Indians escorted him to meet the Oglala activist Russell Means, the Sicangu holy man Leonard Crow Dog, and the Ponca activist Carter Camp. The Oglala also received a delegation from the Six Nations of Iroquois Confederacy that shared the Lakota’s struggle for self-determination.

The besieged Indians – buoyed by numerous solidarity demonstrations in the US and abroad by antiwar groups, Chicanos and Black Panthers – held off for 71 days. On the 59th day of the siege, Buddy Lamont, an Oglala Vietnam veteran from Pine Ridge, was hit by M-16 fire and bled to death. The White House promised to investigate AIM’s complaints. The Lakota disengaged in early May.

Wounded Knee II, as the confrontation became known, galvanised the American Indian sovereignty movement. Politicians took note. In 1975, Congress passed the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act, which empowered tribes to enter into contracts with the federal government. They could administer their funds and run their own schools; they could exercise sovereignty over their economies and education. After a century and a half of US paternalism, Native nations negotiate over federal programmes – and turn them down.

Then, in 1980, after more than six decades of litigation and lobbying, the Supreme Court ruled that the US government had violated the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty in which it had pledged that the Great Sioux Reservation, including the Black Hills, had been permanently preserved for the ‘absolute and undisturbed use and occupation’ of the Sicangu, the Oglala, the Minneconjou and the Yanktonai. The court awarded the Indians $17.5 million as compensation, a sum that is today, with retroactive interest, more than $1.2 billion. The Lakota refuse the money – they want Pahá Sápa back, a principled stance that is vital for the larger battle for Indigenous sovereignty.

The Native American push toward self-determination seemed unstoppable. Congressional acts legalised tribal casinos, defined the criteria for the repatriation of sacred items and ancestral remains, and established laws to protect authentic Indigenous art. The Ronald Reagan and the George H W Bush administrations both reaffirmed the United States’ government-to-government relationship with Indian tribes, and in 1994 the president Bill Clinton met the leaders of 322 federally recognised tribes on the White House lawn and welcomed them home. ‘It has taken the United States and the Indian nations 200 years to come to the point where we can begin to deal with one another as sovereign nations,’ responded gaiashkibos, the president of the National Congress of American Indians.

Obama suggested that Congress return part of the Black Hills to the Lakota and the other Sioux nations

Wounded Knee II elevated the Lakota into renowned Indigenous freedom-fighters. They now commanded the attention of government agents, human rights activists, presidents and Hollywood. For decades, they had fought a losing battle to ban beer trade into their reservations, and in the summer of 1999 the battered bodies of two Lakota men were found in Whiteclay, the ‘little Skid Row on the prairie’. AIM arrived once more in Lakota country. The Anishinaabe activists Vernon Bellecourt and Dennis Banks joined Russell Means to lead a march into Whiteclay, delivering mayhem and claiming the hideous border town for the Oglala nation. With Wounded Knee II echoing in the background, hundreds of protestors squared off with the Nebraska State Patrol and the Pine Ridge tribal police. The old clash between traditionalists and progressives burst to the surface, and another standoff seemed imminent.

Clinton helicoptered into Pine Ridge, becoming the first president to visit an Indian reservation in more than 60 years. Harold Salway, the president of the Oglala Sioux Tribe, welcomed Clinton into a sovereign Native nation and then edified his counterpart of the realities of Indian country: Pine Ridge’s 73 per cent unemployment rate, its life expectancy of 45, its need of basic infrastructure. While many Lakota valued the visit – part of the president’s poverty tour – it was not enough. It was like ‘cramming 2,000 years of history into 10 minutes’, said Milo Yellow Hair, the tribe’s land director.

The Lakota had made a classic cameo appearance in the Clinton years. The Indians briefly held centrestage in US and even international media. US politicians have frequently engaged with suffering Native communities but, more often than not, the real work of solving problems has been left to the Indians themselves. Since the late 1990s, the Lakota have built community colleges, libraries, research centres and casinos, and they have litigated the closing of Whiteclay beer stores, ending the generations-long ‘liquid genocide’. Yet poverty still gripped their reservations, and alcoholism, drugs, malnutrition, diabetes and suicides kept claiming lives. Racism, both overt and hidden, manifested itself in the hiring practices, funding allocation and judicial system of South Dakota and Nebraska. Many Lakota did not feel welcome in Rapid City and Bismarck, or other nearby cities.

But they were known across the world, and they enjoyed the attention of powerful allies. A 2012 United Nations investigation recommended the return of the Black Hills to them and, two years later, Obama visited Standing Rock where the US president announced that ‘nation-to-nation relationship with Indian Country isn’t the exception; it’s the rule’. He suggested that Congress could return part of the Black Hills to the Lakota and the other Sioux nations. The momentum for Indigenous sovereignty seemed unstoppable.

Trump’s authorisation of the Dakota Access pipeline in 2017 challenged and also galvanised the Indigenous sovereignty movement. Everything the Lakota had achieved and endured – defying an aggressive empire for generations, killing Custer, surviving a massacre, leading the battle for Indigenous rights, holding on to the Black Hills while rejecting monetary compensation for a broader principle, and carrying the mantle of being the most celebrated Indigenous nation on Earth – seemed to crystallise into a remarkable global moment.

And, as in 1973, the world took note. People started travelling to Standing Rock from all over the globe. Trump’s decision to halt the Army Corps of Engineers’ ongoing environmental review – which included considering alternative routes for the pipeline – was condemned as a case of racism and a clear move to undermine Indigenous sovereignty. Thousands of people arrived to protest and show solidarity, defying attack dogs, rubber bullets, concussion grenades and mace. The Trump administration seemed unfazed, and state authorities closed the protest camp. Within a year, the Dakota Access Pipeline had leaked at least eight times.

Unlike the treaty violations and the shattering of the Great Sioux Reservation in the 19th century, the most recent assault on Lakota sovereignty unfolded while the world watched. In the spring of 2018, delegates from numerous Native nations joined Lakota in Laramie, Wyoming for a commemoration of the 150th anniversary of the Treaty of Fort Laramie. The multitribal event honoured an Indigenous sovereignty that predates US sovereignty, has never been ceded, and was explicitly recognised in 1868 by the US in the form of the Great Sioux Reservation. The speakers – Lakota, Cheyenne and representatives from many other tribes – talked about the United States’ treaty violations and unfulfilled treaty obligations, their tone ranging from critical to angry and sometimes bitter and hopeless. They talked about what it means to be pushed aside and forgotten, as if your words, thoughts and life do not matter, but they also talked about what it takes to fight for relevance and to be heard. They talked about poverty, alcoholism, diabetes and the departed, gone too early, and they talked about survival – physical, political, cultural and spiritual. They talked about self-determination in their everyday lives – not having liquor stores whose only function was to sell alcohol into reservations on their borders, and they talked about spiritual rights and sovereignty, how they must have the sacred Black Hills back. Young people shared their gratitude for the elders, for their wisdom and lessons, and the elders shared their trust in the younger generation whose determination to continue the fight for recognition and rights was awesome. They were insisting, not hoping, to be heard.

Indigenous sovereignty still faces denouncers, haters and contemptuous foreign governments, but there is real momentum now too. A new era of Indigenous solidarity and sovereignty beckons. In August 2019, the principal chief Chuck Hoskin Jr nominated Kimberly Teehee – the vice president of government relations for Cherokee Nation Businesses and the director of government relations for Cherokee Nation – as the Nation’s delegate for the US House of Representatives. He did so on the basis of the 1835 Treaty of New Echota, which provided the legal basis for the forcible removal of the Cherokee Nation from Georgia, while also codifying the right for the Cherokee to send a delegate to the US Congress. ‘Over 184 years ago, our ancestors bargained for a guarantee that we would always have a voice in the Congress,’ explained Hoskin. ‘It is time for the United States to uphold its end of the bargain.’

The author would like to thank Tiffany Hale for her insightful comments on this essay.