There was a time in my life when gaming was the order and substance of my day – every day, and most nights too. I practically lived in casinos. As part of a pro blackjack team who shared lodgings and ate meals together, like family, I pursued an itinerant loop that took in Las Vegas, Atlantic City, London, Strasbourg, the Costa Brava and the French Riviera. We went where the mood and the scent of money took us.

Wherever we landed, we dug in for the long haul. For 10 hours a day, sometimes more, we would be fixtures at the card tables, playing a meta-version of blackjack (‘twenty-one’) that entailed dutifully counting cards while trying to blend into the background. The idea was to look as inconspicuous as possible amid voluble holidaymakers and hardcore regulars: to look, in fact, as though we were having fun. And I did have fun, but in the spirit of an ethnographer delighted to be admitted to the field of action as a participant-observer. I found the work relaxing – metronomic, hypnotic. After a while, I learnt to detach from it and dwell, meditatively, with my own thoughts.

Over long weeks and months of play, my eyes grew dark-adapted and my circadian rhythms were brutally upended. I’d want breakfast at 4pm, experience a powerful urge to sleep at noon, and I longed, above all else, for fresh air. At night, I dreamt of cards, a giant hand in the sky dealing me one after another as I kept a running count, the suits and numbers drifting lazily before my mind.

There were darker times, too, when a creeping anomie meant I was no longer sure who I was. I felt smothered by my regular Stateside uniform of baseball cap and sweatpants, by having to act the goof. In continental Europe, the strain cut in opposing directions. It demanded that I live up to a polished, card-sharpish coyness. Was this a truer me?

When I wasn’t actually in the casino, I stayed in some very strange places: cookie-cutter apartments with paper-thin walls, arrayed in keyhole shaped cul-de-sacs over Las Vegas’s suburban hinterlands; the wind-battered brick tenement where Louis Malle filmed Atlantic City (1980). Perhaps strangest of all, a fold-out bunk bed in a trailer near Basel. The trailer belonged to Albert Schweitzer’s ne’er-do-well grandson, a bearded bear of a man known to his friends as Dadu. The January night I stayed, snow was piled two feet high outside the trailer. Shivering inside, my breath emerging in crystalline puffs, I nursed $10,000 in cash, stashed inside a fanny belt like a freakish pregnancy, and wondered why the hell we weren’t staying at a hotel.

I rarely talk about my two-year stint as a professional blackjack player, since it tends to hijack the conversation. More importantly, I didn’t want my father finding out. My father had gambling in his blood. He was hopelessly, joyously addicted: to the horses, friendly wagers, kalooki, and most of all roulette. Ever since I was a child, I’d set myself up as his know-it-all, moralising conscience.

There was plenty to tut-tut over. Holiday trips to the south of France derailed to Monte Carlo, when my father would dive into the casino in the middle of the day, leaving my mother and 10-year-old me sweltering at a local café, with a melting Liégeois for company. Meals out were cancelled after he’d lost every last silver at the tables; it’d be make do and mend instead of the new dress I’d been promised for New Year.

My mother tells of countless fretful nights she spent alone, early in her marriage when the glow of romantic coupledom ought to have embraced them both, waiting for my father to return home from God knows where. She’d hear the lock turn at 3am and discover him on the stairs, polished shoes paired in one hand, tip-toeing his guilt, his dark suit glistening with London mizzle.

There was always some sob story, and by way of a punchline he’d turn out his elegant pockets to prove he didn’t have a sou. When my mother relented, he’d charm her with tales of his gaming prowess and maverick fortune. She never stayed cross at him for long. I was less forgiving. His gambling intruded on our family life and pinched it out of shape. It was the dark leitmotif of my childhood.

Dad had somehow acquired his chips from the Ritz in Piccadilly: they had the feel of money without being such

Sometimes my parents hosted roulette evenings at our house. I’d help my mother open up the folding table, topped with green baize, then the two of us would sidle crab-like to lift the roulette wheel (where did it come from?) atop it. There was also a roll of felty turf to unfurl, marked with odds and evens (the 19th-century parlour game from which roulette evolved) and the 36 number squares corresponding to the black and red cups on the wheel. There was one green zero, harmless in a domestic setting, but in casinos the zero (or zeros, for there are two on American wheels) gives the house its guaranteed advantage: if the ball lands on it, the croupier makes a clean sweep of the table, and there are no payouts.

For as long as I can remember, the clatter of the ball bumping round the roulette wheel has been lodged in my head: white-knuckle plastic skipping, looping and jumping over red cups alternating with black, followed by a hard-edged burr – a trrrrrrrrrrrrr, then plop. It was my cue to trill Faites vos jeux! and Riens ne va plus! as the adults rushed to pile their chips on the felty board. I loved the gentle clackety-clack of those chips being stoked and played, like the sound made by worry beads. Dad had somehow acquired his chips from the Ritz in Piccadilly. I remember being struck by their craftsmanship and unexpected heft. They had the feel of money without being such.

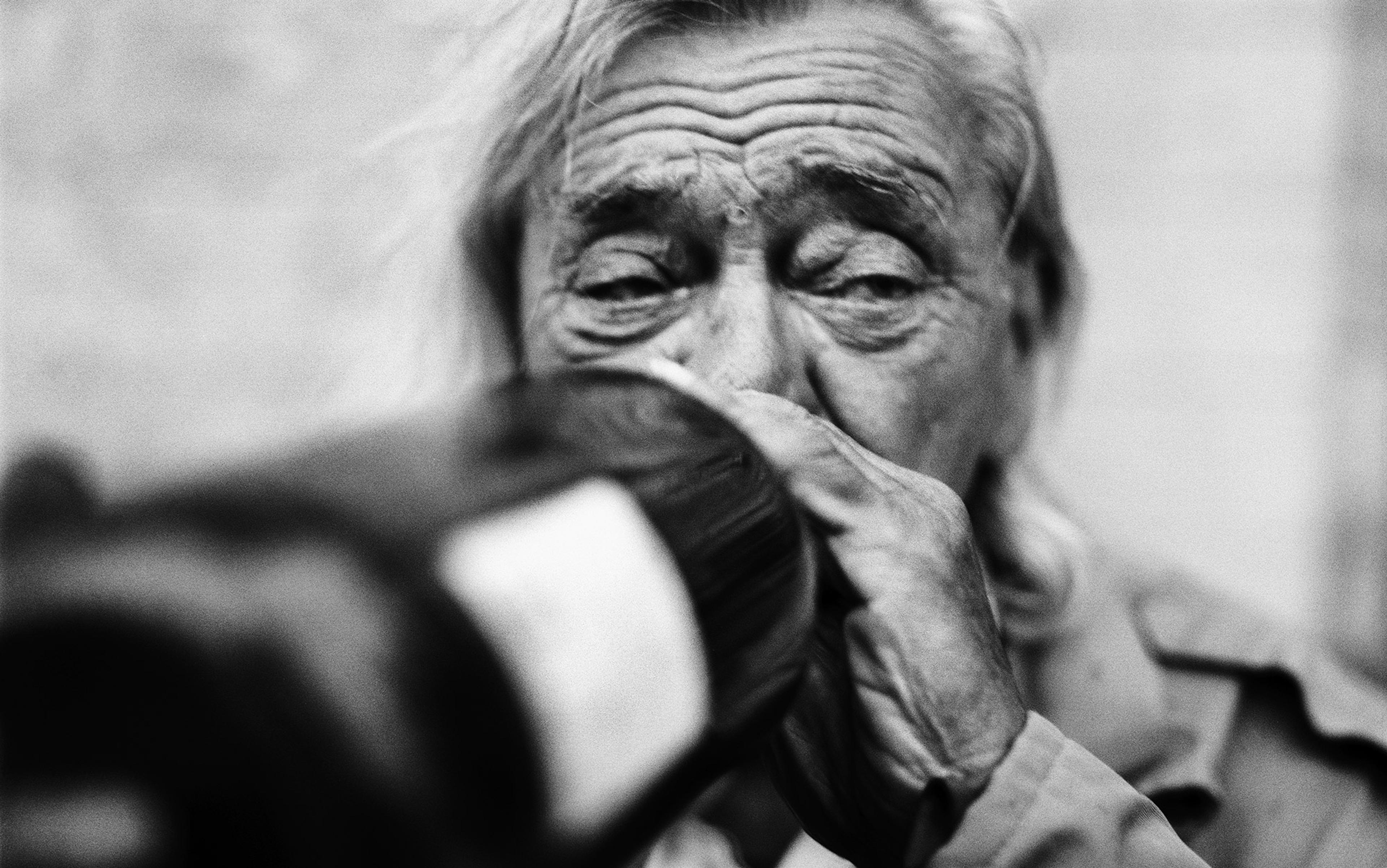

What I recall most vividly is my father’s physical transformation before the great God of Chance. His eyes would bulge, and beads of sweat jewelled his upper lip. He was beyond excited, to the point of agitation: a boy-man in thrall to the wiles of Lady Luck. His gaze locked on the sparkling mirage before him – the glinting chips on the sea of baize, the grating sound of the ball on the wheel – he gave himself up to whatever fate had in store for him. I was a child then, and judgmental, but I vowed that I would never surrender my intelligence to something as mercurial and fleeting as the luck of the draw.

Why do people enslave themselves to games of chance? I’ve asked myself this many times. I’ve talked to experts, done my reading. But the sum of explanation amounts to less than its individually insightful parts. In a fragment written in 1929 or 1930, the philosopher Walter Benjamin identified the gambler’s particular brand of ecstasy, what he termed the ‘remarkable feeling of elation’ that comes with a win. It is a feeling ‘of being rewarded by fate, of having seized control of destiny’. The gambler, in other words, is after a high.

Benjamin noted the appeal of a ‘danger factor’, which arises ‘not so much from the threat of losing as from that of not winning’. Pushed to the limit – the tiny precipice that is the gambler’s natural habitat – the threat of not winning carries with it the risk ‘of arriving “too late”, of having “missed the opportunity”’. Here lies an anxious thrill all of its own that coalesces into an intense presence of mind, which the gambler, in turn, understands as ‘divination’. Thus is born a kind of magical thinking that untethers the gambler from the world, and claims him, for as long as the game casts its spell.

Long before I entered my first casino, our team leader, a former research scientist whom I’ll call Kent, asked me if I ever gambled. We were holed up in a London hotel room at the time, going over and over ‘basic strategy’ until I had it down pat. Basic strategy covers how to play blackjack so as to minimise your losses to the house: it dictates when you should ‘hit’ (tap the dealer for a card), ‘split’ (separate two tens), ‘double down’ (double your bet) or ‘surrender’ (give up and let the dealer win), in accordance with whatever up-card the dealer has. Along with card-counting, it was the cornerstone of my training.

the gambler has a contempt for probability that constitutes an offence against mathematics

Casinos want only one thing, Kent explained: to induce you by whatever means to part with your money. So I need you to stick to the rules, he’d said. Since the rules were mathematical, there would be no room for magical thinking. In any event, I meant to stick to them without question since the money which the casinos wished to part me from was his.

‘I never gamble,’ I had told Kent, truthfully. I couldn’t see the point. Why bet on games that were purely aleatory? Even more idiotic, it seemed to me, was to bet on games that are stacked against you, like the lottery or slot machines. But the gambler has a contempt for probability that constitutes an offence against mathematics. As Fran Lebowitz, American doyenne of the acerbic one-liner, summed it up: ‘I’ve done the calculations, and your chances of winning the lottery are identical whether you play or not.’

If you are immune to gambling’s allure – its sensory seductions, its hokey promises of a win – you start to see through the hidden numbers and spinning dials and flashing lights to the machinery beneath. When I see people with holes in their shoes buying lottery tickets they can ill afford, I can think only of Karl Marx’s ‘opium of the people’. Observing the grey-rinse brigade playing one-armed bandits in Vegas’s teeming slot-machine alleys, I marvel at how these women (and it is overwhelmingly women) have managed in retirement to find a pastime that so precisely mimics the piecework of the production line.

Surely it is a mark of late capitalism’s descent into decadence when, for sheer entertainment, we simply throw money away? When our play trumpets itself as a parody of the means of mass production?

Despite weeks of training, I was unprepared for the casino’s incredible assault on the senses: its endless clanging din, its pulsing bright lights, its multitude of mirrors, its smell. No one tells you about the smell – part sweaty anxiety, part stale snack food ground into the carpet pile. It gets inside your nostrils and remains there, with no fresh air to flush it out. Windows, like clocks and daylight, are excluded from casinos by design.

That first time I was so dizzied by the sensory swirl that reaching the blackjack table felt like dropping anchor in a swell. It steadied me. Within an hour or two, the blackjack drill having kicked in, I began to feel like a pro, counting cards easily (even while chatting) and losing Kent’s money, like he said I would.

In 1966, US mathematician and stock-market investor Edward O Thorp published Beat the Dealer: A Winning Strategy for the Game of Twenty-One (1966), which outlined card-counting and basic strategy for a popular audience. After that, waves of pro blackjack players began to stalk US casinos, trying to wrest from them the game’s inbuilt house advantage, using nothing more than mathematical nous, feats of memory and a hawkish eye. Professional players, unlike cheats, know only what any other player at the table knows. They simply process that information differently – and without recourse to microcomputers, magnets or other illegal devices.

After Thorp, came Ken Uston, Stanford Wong, Don Schlesinger and a string of other mathematician-gamblers who built on and refined blackjack techniques. Between them, they devised ‘shuffle tracking’, a way of keeping tabs on clumps of cards that the dealer has failed to shuffle properly, and ‘ace tracking’, which as-good-as-damn-it lets you follow an ace. Pro players with excellent recall can track numerous aces through an entire game, while simultaneously shuffle-tracking and card-counting. On the inside of their heads there plays a continual symphony of mnemonic tags, pluses and minuses, and card sequences: trains of nonsense, such as ‘kinky cutie, heaven’s alive, tricksy queen’. If they can manage to order a martini on top of all that, then I reckon they deserve to win.

At the Barona Casino in San Diego, a blackjack Hall of Fame honours the greatest blackjack experts and professional players of the past half-century. Las Vegas, meanwhile, is host to its nemesis – the infamous blackjack blacklist compiled by the Griffin Agency, a private detective outfit that specialises in helping casinos root out professional players. Between them, they hint at another game that’s in play: that of cat and mouse.

For almost a month, we dined in style, eventually drinking the cellar dry of Château Margaux

Inside the casino, everyone is watching everyone else. The dealers watch the punters, the pit bosses watch the dealers, while eyeball-shaped cameras on the ceilings record every play at every table at all times of day or night. Money is easy temptation, and casinos need to protect their assets. More accurately, they need to guard their house advantage, engineered one way or another into every game, against professional players whose probability-based play will, over time, swing the pendulum of advantage their way.

Casinos cottoned on to card-counters early. The pro players, for their part, ducked further under the radar by masking their skilled play and acting the fool, or posing as high rollers – that is, punters who take inordinate pleasure in losing large sums. By way of reward, casinos ‘comp’ high rollers with high-end dining, star-studded shows and luxury hotel rooms, all of which entices them to stay longer and lose more. One time, in Vegas, Kent and I duped Harrah’s into believing we were high rollers. For almost a month, we dined in style, eventually drinking the cellar dry of Château Margaux.

Many well-known pros, Kent included, resorted to disguising themselves; dying their hair, wearing coloured contact lenses. If they were a little paranoid, imagining that the Griffin Agency had their mug shots pinned to its walls, they were also tickled by the idea of being ‘Wanted’. They took great pride in their skilled play. Not least because of the steeliness it called for, the margins of advantage being so slim that you’d often lose money for weeks on end before the tables turned.

I was only ever thrown out of a casino once in a melodramatic showdown involving harsh words of public rebuke and ostentatious frog-marching – all the way to the casino’s entrance, which Kent and I were told never to darken again – the better to deter other sharps from taking them on.

The word casino, meaning ‘little house’, derives from the Italian ‘casa’. The promise is that the casino will open its doors to you at all hours and embrace you. Just like home. You can stay for as long as you like. In fact, the casino does not want you to ever leave. It offers itself up as a bounded field of play that is safe as houses, like a soft-play centre for grown-ups. The illusion is that you cannot hurt yourself in a casino. But, of course, you can.

The more time I spent playing blackjack, the more opportunity I had to observe other players and, in observing them, to return to the question that vexed me for so long, of what made my father tick. I noted that, like my father, blackjack players bet on ‘magic numbers’ such as birthdays and anniversaries. They exalted in the ego-tripping feeling of having special agency. They made private appeals to the gods of chance. The dealers were their intercessionary angels (‘Give me an ace, baby!’) At some level, I understood their magical thinking: it was a means of inserting themselves into the game, so that their play could serve as a conduit between them and, well, the forces of fate that governed the cosmos.

Beginning with Erving Goffman, whose own ethnographic researches led him into a deep enmeshment with casino culture (he not only played pro blackjack, but trained as a Vegas pit boss), sociologists and other researchers have interpreted the gambling impulse as a desire to model, rehearse, refract and delineate the possibilities offered by real life, but in a parallel dimension. In 1971, the Hungarian psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi suggested that games of chance delimit ‘a slice of reality with which the player can cope in a predictable way’: the player begins to foresee its possibilities and so achieves a measure of control over his environment. More recently, the anthropologist Thomas Malaby at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee has argued that gambling provides ‘a kind of distillation of chanceful life into a seemingly more apprehensible form’. On this view, casinos might be seen to conform to a broader understanding of play as a kind of rehearsal or playing out of the real world, but in a contained, non-consequential form. Like the child who pretends to cook or who make-believes doctors and nurses, role-play affords the gambler a means to test boundaries – their own, as well as the world’s – as they explore the workings of risk, hazard and chance.

The promise of safety is paramount – and carefully crafted. It is embodied in the conscious shift in terminology of recent years, from ‘gambling’ to ‘gaming’, and in every detail of the casino’s garish, fun-house aesthetic. Trust me, the casino whispers over and over, and the gambler is lulled into a happy acquiescence. Perhaps this is why my father found casinos so appealing: he was intoxicated by the illusion that however reckless he wished to be nothing there would ever hurt him.

The same illusion is at work in what the British sociologist Anthony Giddens has termed our ‘risk society’ – a scaled-up fun-house, in which the powers that be literally bet on the future (gambling, sometimes recklessly, on the climate, the stock market, the health of the economy and population) and assume that somehow we’ll be okay. According to Giddens, what enables us to take outlandish risks and yet simultaneously believe in our continued safety is the Umwelt. Developed by German semioticians in the 1960s to denote the way individuals customise their environment as they interact with it, the term is usually taken to mean ‘self-centred world’.

As Giddens reads it, the Umwelt constitutes a mantle of trust under which a society or individual manoeuvres, knowing that the world won’t bite back. It is an envelope of psychological security, or ‘protective cocoon’. By regulating our internal settings to ‘comfortable’, it deflects ‘the hazardous consequences that thinking in terms of risk presumes’. I’ve never come across a better rationale for the myopia that is short-termism.

What the Umwelt tells me about my father after all these years is strangely humanising. It suggests that in spite of taking great pains to appear otherwise, he was actually risk-averse, terrified of the world’s essential unknowability. Gambling gave him a sense of potency he otherwise lacked, and swept him up in the romantic fantasy of the swashbuckling hero. More importantly, it assured him that he could be rewarded for risk-taking without ever being put to the test.

slot-machine players, pinned to the spot by their addiction, feel a tidal sense of relief, even joy, when they lose

Against the ‘Goffman consensus’ that styles gambling as a kind of rehearsal of life, scholars such as the anthropologist Natasha Dow Schüll at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (and others, notably Matthew Crawford, who has written so well on the attention economy) perceive a techno-narcotic tendency at work in the experience of gambling. Slot-machine players, in particular, demonstrate a craving for ‘automaticity’ – or a state of pure passivity, in which they become at one with the machine. This qualifies as ‘play’ only in a flipped, toxic sense. It kindles an absorption born not of focus and concentration, but its reverse – an alienation so profound you no longer connect to the world. It’s more like ‘being played’.

Studies by Schüll show that slot-machine players, pinned to the spot by their addiction, feel a tidal sense of relief, even joy, when they lose. Only when they have lost every last cent are they finally free to walk away. In her magisterial study of the slot machine business, Addiction by Design (2012), Schüll reports that hardcore players will frequently soil themselves rather than abandon post – which lends an entirely new dimension to the idea of being a hostage to fortune.

Conversely, when the slot machine lights up wildly and chimes a win (video screens having replaced arm-pulls and clanging coins to cut out needless action), the gambler feels a sense of near despair: they will now have to stay put for as long as it takes to lose the money all over again. Losing, far from registering as defeat, is the accepted price the gambler pays for the experience – the thrill – of being satisfyingly distracted while being skillfully, and surreptitiously, fleeced.

Casinos and gambling do real damage to people. I’ve seen it. Gamblers don’t toy with chance and possibility the way computer scientists run multiple simulations in order to determine the outcome of an event. Instead, gaming gets into a gambler’s soul, like a piece of malware, affecting how they think and feel, merging with their actual life and then dominating it. It’s not out there, a calculated model of the world: it’s inside, like a virus.

My father was never able to cure himself of the gambling impulse: all his life he remained a saucer-eyed slave to the beating drums of the tables. He lost an awful lot of money over the years; and we lost an awful lot of him. Casinos robbed him of the ability to distinguish what was real from its simulacrum. Instead of offering him a way of rehearsing his actions in the world, gambling became a substitute for it.

My father was a prime candidate for being played. He was a gullible soul and, although willful, he was cowardly when challenged. Rather like a child, he had difficulty imposing his intent on the world. By encouraging him to remain stuck in play, casinos kept him infantilised. In this regard, my father had something in common with Schüll’s slot-machine junkies: frustrated by a world grown too complex for them to exercise will, they reduce their interaction with it to a single manageable exchange: push the button or not. Bet or not. Play or not.

I find this terribly sad, and of course it doesn’t account for what drew me to pro blackjack myself. There was the adventure, to be sure: the glamour, the edginess, the slight odour of fear that preceded it (in all these things I am unlike my father). But also, I never chose professional blackjack. It found me, and I jumped at the opportunity for reasons that went far deeper than I first realised. Just as the child of an alcoholic worries that the apple never falls far from the tree, I needed to discover once and for all whether my hostility to gambling might not just have been born of recognition. In other words, what if the malware was in me too?

The first time my ace-tracking paid off, delivering me a cupid’s arrow of ‘A’s strung together with a heart, I experienced an undeniable high. ‘Hit me,’ I cried, knowing that my chance of getting a 10 (all picture cards carry a value of 10 in blackjack) was five times higher than of getting any other card. As Kent instructed, I had put thousands of dollars on my box. I tingled with nervous anticipation. When the 10 arrived, the surge of relief that followed felt very much like joy. Both feelings, of course, mark the end of a state of suspension, the bubble-piercing re-entry into the world of cause and effect. Yet what remained after the elation passed was my satisfaction in having captured that ace: the win, even my cut of it, was neither here nor there.

Perhaps the more interesting question is why I stopped gambling. At one level, the answer is easy: I got bored. But that’s too easy. Looking back, I think that it took me years to finally see that while pro blackjack possesses all the trappings of work – calculation, investment of time, skill, profit – it isn’t work, only its simulacrum, just as gambling is merely a simulacrum of play. This was the lesson that really hit home. It told me that in order to have the very thing that my father didn’t – will, in the world – I needed to give up the pretence of work and grow up, and then find something genuinely consequential to do with my life.