At the International Military Tribunal for the Far East (1946-48), convened to try Japanese military and civilian leaders for war crimes, one defendant delivered a puzzling explanation for Japan’s 1937-45 war against China. The aim of the struggle, he said, had been to make ‘the Chinese undergo self-reflection’, adding: ‘It is just the same as in a family when an older brother has taken all that he can stand from his ill-behaved younger brother and has to chastise him to make him behave properly.’ That defendant was General Matsui Iwane, commander of the army that devastated Shanghai before perpetrating the Nanjing Massacre in December 1937. According to the Military Tribunal, at least 200,000 were murdered and 20,000 women raped in the first weeks of the city’s occupation.

For Iris Chang, author of the controversial bestseller The Rape of Nanking (1997), Matsui’s words ‘summed up the prevailing mentality of self-delusion’ among the Japanese that the war against China was intended to create a better China integrated into Japan’s ‘Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere’. Yet when we dig deeper into Matsui’s background, other puzzles emerge. He was the son of a former samurai and Confucian scholar, and shared his father’s deep interest in Chinese culture. Prior to the war, Matsui often visited China, becoming acquainted with Chinese nationalist leaders such as Chiang Kai-shek and Sun Yat-sen, whom he admired. Like Sun, Matsui professed to be a Pan-Asianist.

According to Matsui’s Pan-Asianism, Japan had a mission to unify Asia, first by rescuing it from the oppressive yoke of European imperialism. This mission included relieving China from its ‘miserable condition’ of subjugation. But if China’s leadership proved disobedient to Japan’s brotherly paternalism and succumbed to foreign ideologies such as communism, it needed to be ‘punished’ and brought to its senses. Matsui’s liberationist rhetoric on behalf of China also coincided with material interests in enforcing a Japanese ‘Monroe Doctrine’ for Asia.

Matsui Iwane riding into Nanjing, China on 17 December 1937. Courtesy Wikipedia

Matsui was far from alone in his belief that China’s punishment was for the sake of lofty Pan-Asianist ideals. Leading Japanese Confucian scholars shared his convictions. It seems incredible, on the face of it, that Confucians would support what was nothing more than military aggression. Originating 2,500 years ago in the Warring States era, Confucian tradition typically emphasises the cultivation of virtue and ritual propriety as a basis for ‘Kingly Way’ rule by moral suasion, rather than by force. Confucians like Mencius chastised rulers who ignored the welfare of their subjects while they emptied their treasuries to build up military power. So how could Japanese Confucians moralistically uphold Japan’s wartime aggression against the homeland of Confucius himself?

Long established in Japan, Confucianism underwent a Tokugawa-era renaissance stimulated by late-16th- to 17th-century transmissions of Neo-Confucian learning from Korea and China. Alongside Buddhism, Confucian learning enjoyed the official patronage of Japan’s shogun rulers – but not without major changes. Political-cultural factors peculiar to Tokugawa Japan conditioned the reception to Neo-Confucian learning, incentivising modifications and syncretisms that had long-lasting effects down to the 20th century.

As rulers of a hereditary, military caste-based system of governance, the Tokugawa shoguns were sensitive to political ideas that might threaten their legitimacy, and unreceptive to Confucian convictions about the moral fallibility – and perfectibility – of rulers. Ancient Confucian endorsements for ministerial prerogatives to depose or execute rulers who had forfeited Heaven’s Mandate, or Confucian suggestions that rulers could pass on their throne to virtuous successors not related by blood, were not tolerated. Chinese-style civil service examinations based on Neo-Confucian learning had only limited uptake in the caste-based Tokugawa social order.

In the Tokugawa era, the imperial court was located in Kyoto, firmly under the shogun’s power. However, during this period, traditional Shinto beliefs about the divine origins of Japan’s emperors became the focus of scholarly attention, offering source material for a syncretic ‘Japanisation’ of imported Confucian doctrines, which elevated the spiritual importance of the imperial family. As early as the 17th century, some Confucian scholars like Yamaga Sokō were claiming that Japan, not China, deserved to be called ‘The Middle Kingdom’, since its people practised virtue consistently under an unbroken imperial line, whereas China was beset by constant dynastic changes and instability.

This doctrine still clung to upholding the shogunate by appealing to its delegated authority from the imperial line

By the early 19th century a sense of crisis was gathering, as awareness grew of the military might and imperialist ambitions of the European powers. Scholars associated with the Mito School, a school of thought synthesising Confucianism and Shintoism, responded to this perceived threat with proto-nationalist theories for fostering the spiritual and moral unity of the Japanese. One of its scholars, Aizawa Seishisai, developed a deeply influential definition of the mystical concept of the ‘national polity’ (kokutai) for binding subjects’ loyalty against foreign threats.

The kokutai was, for him, a ritual-based order of non-coercive, virtuous rule, originated by the Sun-goddess Amaterasu and passed down by the unbroken line of her imperial Japanese descendants, which unified filial piety and loyalty in a manner found in no other state. Yet this was a doctrine that still clung to upholding the shogunate by appealing to its delegated authority from the imperial line. It took a new generation of reformers, spurred by the appearance of Commodore Matthew Perry’s US ‘Black Ships’ in Edo Bay in 1853 and the first influxes of Western learning, to harness Confucian-Shinto nationalism for the overthrow of the shogunate.

Commodore Perry’s naval squadrons, and acute awareness of the humiliation of China by superior Western firepower in the Opium Wars, induced the Tokugawa shogunate to sign a series of unequal trade treaties with the United States and European powers after 1853. These developments convinced many leading members of the old samurai class that the shogunate’s time was up, and that Japan desperately needed to reform along Western lines. During the civil strife that led to the overthrow of the shogunate and the founding of a modern state under Emperor Meiji’s ‘restored’ imperial rule in 1868, the eyes of ambitious reformers were cast to opportunities abroad, for foreign learning, new technologies and social advancement.

With the departure of growing numbers of Japanese for study abroad, and rapid traffic of foreign legal, political, scientific and military advisors into Japan, reformers’ ambitions were soon fulfilled. Japan embarked on a breakneck industrialisation. Conservative reformers looked to German statism for models in governance, and in educational and military organisation. The Meiji Constitution, proclaimed in 1889, incorporated kokutai imperial foundation myths, and fatefully institutionalised a ‘symbolic’ imperial command over the armed forces alongside provisions for representative government and civic liberties.

Yet, through all these reforms, Confucianism did not decline into obsolescence, even though the old Confucian academies were closing down. It is true that liberal reformers like Fukuzawa Yukichi thought Confucianism had no positive role to play in Japan’s modernisation. Others, however, took a different view.

Inoue Tetsujirō plays a pivotal role in our story. Born in 1855, in the last years of the Tokugawa shogunate, he received a traditional Confucian education in his boyhood, and a European postgraduate education in philosophy at German universities between 1884-90. In the 1880s, as an associate professor at the newly founded University of Tokyo, Inoue conceived a far-reaching project to ‘academicise’ Confucianism as ‘philosophy’ in the European sense of the term, and as ‘thought’ compatible with European history of ideas analysis. Under his influence, the University of Tokyo would become an early powerhouse for Sinological and Confucian studies.

Inoue Tetsujirō. Courtesy Wikipedia

His role after 1890 as a prolific ideologue for Japan’s Ministry of Education also repays attention. Drawing on his studies of German idealist philosophy, Inoue recognised the importance of fomenting a renewed Volksgeist or national spirit among the Japanese to solidify their resistance to Western ideological as well as military threats. He propagated a widely influential national morality doctrine based on a modernised, syncretic Shinto-Confucianism – and on a modern Bushidō mythology that he had a big hand in confecting.

Confucianism came to be seen as the unifying force for Japan’s ‘Pan-Asianist’ leadership of Asia

Inoue’s Confucian study The Philosophy of the Japanese Wang Yangming School (1900) testified to a timely expression of this national morality abroad. In June, an anti-foreigner uprising of ‘Boxer’ rebels and some Chinese Imperial Court factions led to a siege of the foreign diplomatic quarter in Beijing. Some 8,000 Japanese troops joined a multinational force to break the siege. Inoue boasted that the troops of Japan’s expeditionary force distinguished themselves from their European and US allies by ‘manifesting an unparalleled attitude of purity in our national morality … to dazzle the eyes of all nations around the world’. Confucianism was already being invoked to glorify the conduct of the Japanese Imperial Army abroad under the infallible Heavenly Mandate of the emperor, their commander-in-chief. An originally defensive nationalist outlook was transforming into a more expansive vision for Japanese leadership in East Asia, legitimated by its spiritual vitality and military power.

In the years following the First World War, Confucianism came to be seen as a source of spiritual renewal, and as the unifying force for Japan’s ‘Pan-Asianist’ leadership of Asia – just when its status in China appeared to be crumbling under the iconoclastic attacks of the May Fourth Movement. A number of Japanese Confucian and Chinese studies organisations and movements were established, under government patronage, and some of them became very preoccupied with China affairs.

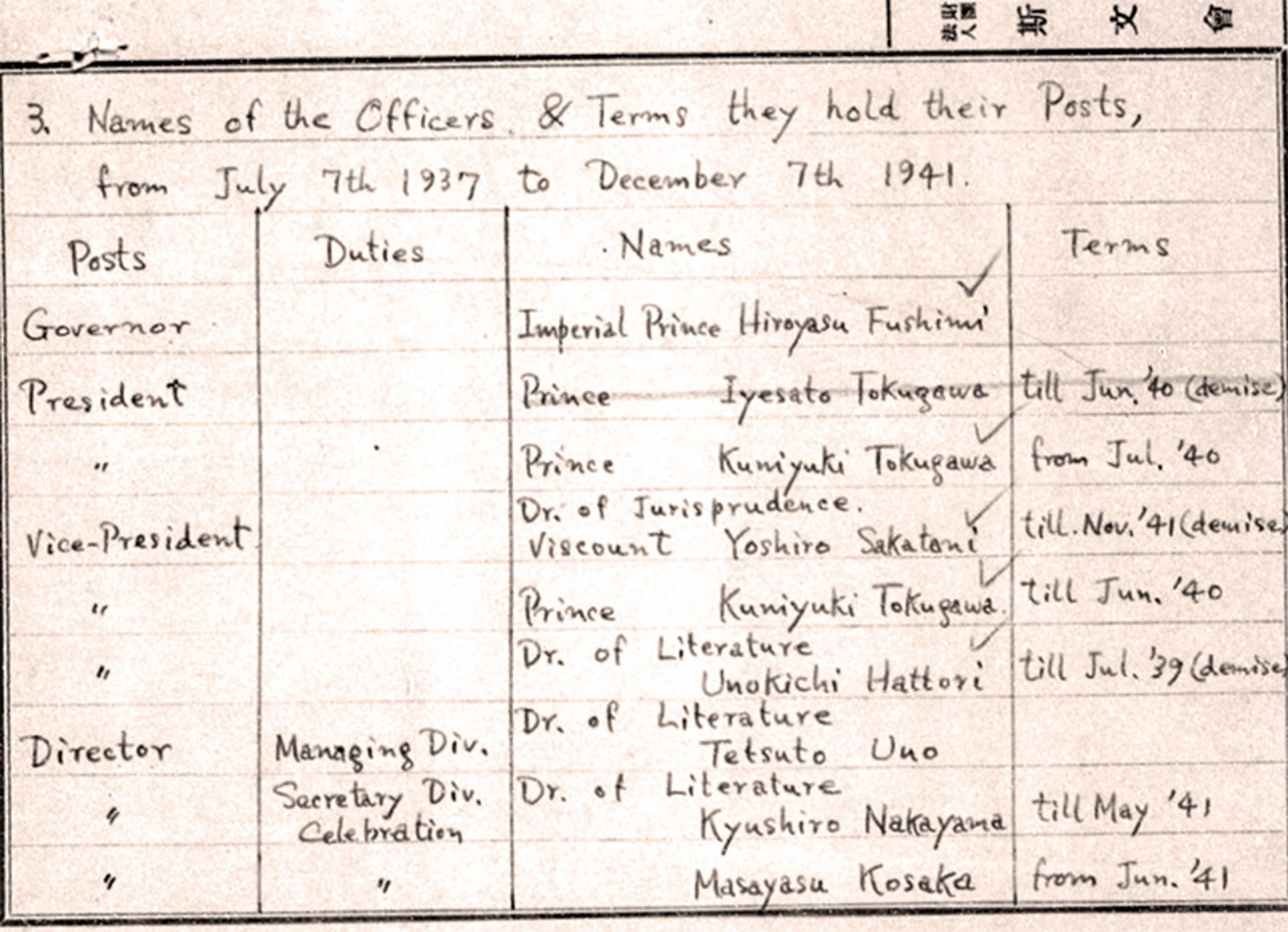

The Shibunkai was a Chinese and Confucian studies organisation of particular importance. It is little known today, and its pre-1945 history has been researched by a small number of Chinese, Taiwanese, Korean, American and Australian scholars. It was founded in 1918 by notables such as the University of Tokyo sinologist Hattori Unokichi, the Chairman of the Privy Council Viscount Kiyoura Keigo and the business tycoon Shibusawa Eiichi. The head of the former Tokugawa ruling family Prince Tokugawa Iesato became chairman of the Shibunkai in 1922, and it gained direct royal patronage with the appointment of Marshal Admiral Prince Fushimi Hiroyasu as its president.

List of leading wartime Shibunkai members compiled in 1947. Courtesy the National Diet Library

Counting now mostly forgotten scholars like Inoue Tetsujirō, the Chinese literature theorist Shionoya On, the historian Iijima Tadao and the philosopher Takada Shinji in its ranks, the Shibunkai aspired to be a research as well as an educational organisation. It campaigned for classical Chinese literacy and Confucian-based morality education in schools, and published studies on the Chinese classics and Confucian thought in its journal Shibun.

Hattori Unokichi in 1936. Courtesy Wikipedia

From early on, the Shibunkai concerned itself with developments in China. The 1911 Revolution in China confirmed Hattori Unokichi’s convictions about the indigenous revolutionary undercurrents in Chinese history – notwithstanding the facts that Japan’s own military and diplomatic actions towards Qing Dynasty China had greatly weakened its legitimacy, and that Chinese nationalist revolutionaries like Sun Yat-sen had taken inspiration from Japan’s modernisation. Yet for Shibunkai scholars like Hattori, what eventually appeared different and disturbing about this Chinese revolution was its overthrow of China’s monarchy for a republic. That was a blow against Confucian loyalty to rulers. Meanwhile, Sun Yat-sen’s ‘Three Principles of the People’ appeared to them to be a heretical synthesis of Western ideologies such as US-style democracy, chauvinistic nationalism and communism.

Factions within Japan’s military took advantage of their elevated position to engage in adventurism in China

In the early years of the Chinese Republic, Japanese officials, and Shibunkai members, began to undertake pilgrimages to the Kong Family Estate in Shandong’s Qufu town, where the young 77th descendant of Confucius, Kong Decheng, and his clan lived. At this time, the estate had become impoverished and neglected. In her autobiography The House of Confucius (1988), Kong Decheng’s sister Kong Demao recalled the interests of Japanese visitors. Some of them were researchers studying the estate, some of them tourists paying respects at the estate’s temples, and some, bearing precious gifts and Confucian texts, took an interest in Kong Decheng. Shibunkai visitors pinned their hopes for improved China-Japan relations on these visits, and convinced themselves that the descendants of Confucius would be suitable rulers of a China reconciled again with its Confucian culture. Chinese researchers have argued that one mission for the Shibunkai ‘was to use Confucianism to assist Japan’s expansion into China’.

The Shibunkai’s scholars didn’t see it that way, of course. They believed they were engaged in a paternalistic spiritual undertaking, exhorting the Chinese to restore the Confucian Way and the monarchical order suited to upholding it. In the 1930s, as factions within Japan’s military took advantage of their elevated position to engage in adventurism in China, with or without the support of civilian government, the Shibunkai went along with subsequent elite group-shifts that normalised expansionism. They even wielded some influence in the direction those shifts took, and this influence speaks to a harmonisation between the ‘spiritual’ interests of the Shibunkai and the material interests of political and military factions seeking control over China.

The Japanese Kwantung Army’s occupation of Manchuria in 1931, undertaken (at least initially) in defiance of Japan’s civilian government, ushered in a new era of political instability and authoritarianism in Japan. Ideological cottage industries moralised Japanese expansionism through two rather confusing notions: the ‘Kingly Way’ and the ‘Imperial Way’. These notions were subject to divergent interpretations by Pan-Asianists, socialists, Confucians and ultranationalist military factions. For General Matsui, the ‘new state of the Kingly Way’, his term for the Japanese puppet regime in Manchuria, was to be a harbinger for a future ‘freedom and glory of Asia’. For some Left-wing reformers, the Kingly Way was a means to realise an egalitarian, anticapitalist agrarian society in Manchuria, and end the strife caused by warlords and by Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist government.

The Shibunkai scholars offered their own hybrid Confucian-Shinto interpretations of the Kingly Way that affirmed Japan’s Pan-Asian mission in East Asia. The Kingly Way of virtuous governance was practised in its highest and most consistent form in Japan, they averred, with its unbroken line of virtuous emperors and its unparalleled unity of filial piety and loyalty. As the 1930s progressed, Shibunkai scholars asserted that Japan’s Confucian-Shinto Kingly Way should be distinguished as the Imperial Way. This all appealed to political and military elite leaders who believed in a Pan-Asian case for a benevolent Japanese imperialism.

That these notions enjoyed government support was demonstrated in the organisation of a grand conference on Confucianism held in April 1935 at the Shibunkai’s base, the Yushima Sage Hall in Tokyo. Attended by government ministers, the puppet emperor of Manchuria, Puyi, and 60 Japanese, European, colonial Korean, Taiwanese and Manchurian scholars, the conference was meant to promote the Pan-Asian, Confucian case for Japan’s leadership in East Asia, and the potential of its Kingly Way to uphold world peace. The Japanese Foreign Ministry assisted the Shibunkai in diplomatic efforts to recruit Kong Decheng and other Chinese Confucian notables for the conference. The Chinese Nationalist government, aware of possible Japanese plans to use Kong as a future puppet ruler in northern China, directed him to stay home, and permitted another Kong family member to attend in his place.

Kong Decheng in 1935. Courtesy Wikipedia

At the conference, Shionoya On denounced Italian military threats against Ethiopia, and repudiated both fascism and Nazi revanchism as ‘outside the bounds of the Kingly Way’. Yet, like his colleagues, Shionoya enthusiastically supported the war against China when it broke out two years later. From late 1937 onward, Shibun magazine began to leaven its educational and scholarly content with a small but significant infusion of war-themed writing, with titles such as ‘The Brutality of the Chinese’, ‘Chiang Kai-shek Knows Nothing of History’ and ‘Confucian War and the Current Situation’. They claimed a Heavenly Mandate for ‘Holy War’ against China.

There are fairly prosaic reasons why the Shibunkai Confucians rallied so enthusiastically for the war. For them, as for many other Japanese at the time, the Imperial Japanese Army was the emperor’s army, and the emperor was morally infallible. Therefore, it was unquestionably waging a righteous, holy war. But that is only part of the story, for the Shibunkai Confucians dug into traditional Confucian thinking on just war to rationalise Japanese military aggression.

A ruler who waged punitive war against a tyrant invited punitive war by his neighbours back on himself

The concept of the ‘decree’ or ‘mandate’ of Heaven is key. In ancient Chinese cosmology, Heaven, as a quasi-divine power, conferred its mandate on rulers who were benevolent and saw to the material and spiritual welfare of their people. The proof of such a mandate was supposedly revealed in the prosperity and peacefulness of a realm under such rulers. On the other hand, a tyrannical ruler could forfeit that mandate, and the proof of that was found in the onset of natural and human disasters, and the turning of his people against him.

According to the 4th-century BCE Mencius and ancient Chinese histories, such rulers invited their own demise, as sufficiently virtuous neighbouring rulers could rightfully claim Heaven’s decree to launch a punitive military expedition to overthrow them. Evidence for that Heavenly decree was manifested if the people suffering under such rulers flocked to the neighbouring ruler’s army and willingly submitted to his benevolence. But expeditions could also be undertaken to punish barbarians. When Mencius lashed out against ‘rebellious ministers and villainous sons’ and heretical scholars who ‘acknowledge neither king nor father’, he compared them not only to beasts, but also to uncultured barbarians who deserved military punishment by sage rulers.

Such a doctrine could be manipulated by would-be aggressors claiming Heaven’s Mandate. So Mencius warned that a ruler who waged punitive war against a tyrant, but then proceeded to plunder and slaughter his subjects, invited punitive war by his neighbours back on himself. Nevertheless, the language of righteous punishment and the Heavenly Mandate suffuses some Shibunkai scholars’ wartime writing. Thus in October 1937, Shionoya called for improved education relating to China. Yet he also argued that for peace to be maintained, ‘the savage Chinese army … must be thoroughly punished and republicanism eradicated’.

In Shibun two months later, Iijima Tadao claimed that since the Chinese had embraced republicanism and communism, they were bereft of filial piety and loyalty, putting themselves in an even more degraded position than that of ancient barbarians. Iijima echoed the reasoning of his Tokugawa Confucian forebears to suggest that Japan, not China, was now the true ‘Middle Kingdom’. The Japanese ‘emperor’s army’ was thereby entitled to ‘punish’ the Chinese, much as Mencius claimed ancient Chinese Sage rulers had punished barbarians. Writing in the same month that Matsui’s army committed the Nanjing Massacre, Iijima added that: ‘We must truly attribute its successive victories in battle to a Mandate from Heaven.’ Still, he hoped this punishment would support Chinese Confucian revivalists trying to bring their compatriots back to the Confucian fold.

This conviction in Heaven’s Mandate and Japan’s righteousness did not waver with the outbreak of war against the US and the UK in 1941. Writing for Shibun in October 1942, Takada Shinji boasted about Japan’s victories over the British and the Americans. He pointed to the secure status of Shandong’s Confucian sacred sites and ‘legacies’ under the control of the Japanese army as proof that the ‘Way of the Sages [was] now being put into practice by the Japanese Empire’. In his last article for Shibun published in January 1944, 11 months before his death, Inoue Tetsujirō wrote that the war was ‘a moral war, waged with the goal of destroying the immoral American and British enemies’.

But were these Japanese Confucians all that influential during the war? They were influential with some regional elites in the empire. From the 1930s to the ’40s, Korean scholars educated in Japan went on to propagate ‘Imperial Way’ Confucianism at the former Sungkyunkwan Confucian Academy in Seoul, renamed as Gyunghakwon during the colonial era. As late as the 1970s, Korean national ethics school textbooks were teaching Japanese-inflected Confucian virtues of filial piety and loyalty, reflecting the colonial-era Japanese education of the South Korean dictator Park Chung Hee and his educational advisors.

The Confucians’ influence in Manchurian and China affairs varied. In the early years of the Manchurian puppet state, the Japanese promoted Confucianism with the collaboration of Chinese traditionalists such as Manchuria’s first prime minister and advisor to Puyi, Zheng Xiaoxu. Shionoya On cultivated a friendship with Puyi, meeting him in 1928 and in 1933 in Manchuria. Shibunkai members also served as ‘China advisors’ to the government in the 1930s. Hattori Unokichi submitted a lengthy policy brief in 1938 to the Foreign Office recommending the postwar establishment of a joint Japan-China ‘Kingly Way’ research institute, and a Confucian university in Shandong.

Perhaps the Shibunkai had their best chance to directly influence China policy in January 1938 as the Japanese army advanced on Shandong’s Qufu city, the home of the Kong family estate where Shibunkai scholars had tried to cultivate Kong Decheng as a future ruler of China. However, Kong and his pregnant wife were evacuated to Wuhan on Chiang Kai-shek’s orders just before the arrival of Japanese forces, provoking false Shibunkai accusations that they had been ‘kidnapped’ by the ‘Chinese warlords’. In Wuhan, Kong declared his anti-Japanese patriotism to foreign reporters, demolishing Shibunkai hopes for him.

Perhaps they were so invested in their ideology that it was unimaginable for them to express dissent

As the war in China bogged down in attritional combat and vicious counterinsurgencies, it seems that Japan’s military leadership lost interest in Confucianism as a means for ‘spiritually’ reconciling the Chinese to Japanese overlordship. Attendance of prime ministers or cabinet ministers at the Shibunkai’s spring Confucian festivals ceased after 1942, which hints at a decline in government patronage. But this was a mere foretaste of the Shibunkai’s deeply diminished standing and visibility after the war, following US occupation-era purges of senior members from their universities, and a sharp Leftward turn in postwar Japanese Sinology.

Much as critics have raised questions about the complicity of the Kyoto School Japanese philosophers and Zen Buddhist intellectuals, we can speculate about the reasons for the complicity of Japanese Confucians who were far closer to – even members of – the wartime political elite. Perhaps, practically speaking, they were so invested in their ideology and in the material benefits of their elite position that it was unimaginable for them to express dissent, even as information about war atrocities in China must have reached them. In that light, the postwar recriminations against them appear morally justified.

What appears astonishing in hindsight is how much Japanese Confucians’ wartime denunciations of the Chinese Nationalist government were at odds with what they knew of its own Confucian aspirations. They knew that, beginning in the early 1930s, the Nationalist government had been sponsoring revived Confucian festivals and rituals, and formalising a modern ceremonial rank and status for the descendants of Confucius. Inoue Tetsujirō grudgingly acknowledged at the 1935 Yushima Sage Hall conference that the Nationalist regime was attempting its own Confucian revival with its ‘New Life Movement’. Following a prewar visit to the Confucian family estate in April 1937, Takada Shinji admitted in Shibun that Kong Decheng’s tutor had rebuked Japan by declaring Confucian disapproval of military aggression to him, and that Kong, rather obviously feigning illness, was unable to meet him. And like Inoue, he admitted that the Nationalists were trying to revive Confucianism – albeit under Japanese influence.

Nevertheless, the Japanese Confucians were just too engrossed in their imaginings of a true, classical Confucian national spirit for China, which they believed flesh-and-blood Chinese could live up to only under Japanese guidance. From their point of view, Chiang Kai-shek’s decision to resist Japan in July 1937 was a betrayal that revealed him to be just another Chinese warlord, incapable of practising the Confucian Kingly Way. Their inability to respect Chinese aspirations for a modern nation state like Japan’s, for a Confucianism that upheld Chinese nationalism rather than Japanese Pan-Asianism, or for a life free from war and occupation, was their greatest culpability.

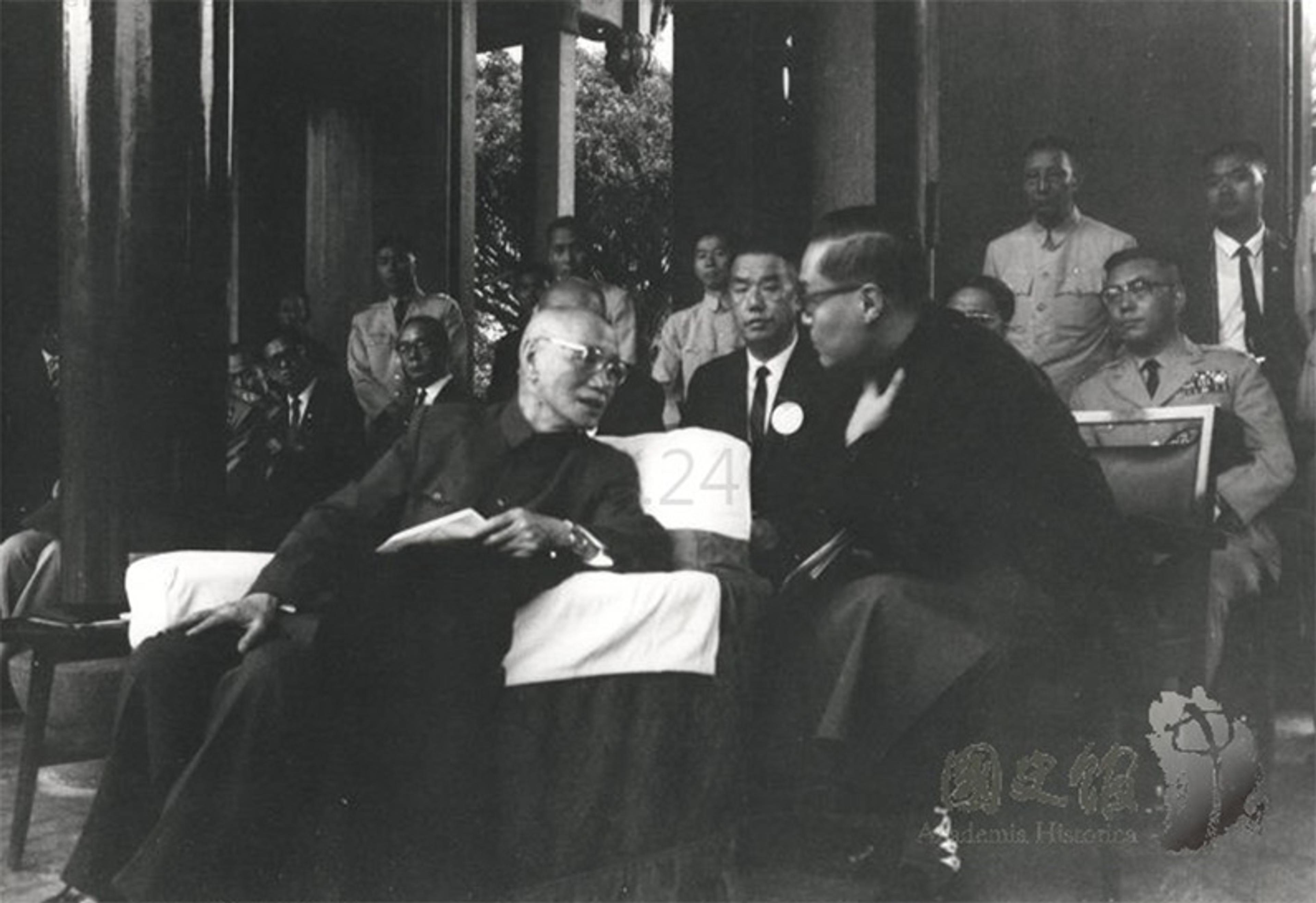

Chiang Kai-shek and Kong Decheng in Taipei, Taiwan in 1968. Courtesy Academia Historica

Eight decades on, is it possible that Confucianism’s still potent cultural legacy will be exploited to moralise the hegemonic ambitions of today’s militarising East Asian power – China – and that another generation of Confucian thinkers will become complicit with those ambitions? Whatever ambitions China’s political elites hold, they appear less interested in using Confucianism for such ends. Anyone reading the bombastic screeds on ‘socialism with Chinese characteristics’ issued in President Xi Jinping’s name will encounter few references to Confucianism, and much sloganeering for Marxist-Leninist dogmas. Chinese Confucian scholars, though numerous and ambitious, lack the official patronage that Japanese Confucians enjoyed in the 1930s. And, in the rest of East Asia, Confucian academic philosophising is politically diverse, synthesising Confucianism’s humanistic elements with progressive and constitutional democratic theories.

Some official efforts, however, are underway to boost the Chinese Communist Party’s cultural nationalist credentials by syncretising Marxism-Leninism with Confucianism. It is not beyond imagination that the Chinese Communist Party may also invoke Confucianism to legitimate the civilisational, Pan-Asian parameters for its own Monroe Doctrine for East Asia – beginning with Taiwan, seemingly in the clutches of US power. In a 2011 essay on the ‘Taiwan question’ by the leading Chinese law professor Jiang Shigong, there is a disquieting presentiment of what imperial Confucian foreign policy would look like if it was adopted by China’s leadership. Reflecting on the centrality of resolving the Taiwan question for China’s destiny, Jiang wrote that China’s reunification with Taiwan and assertion of political leadership in East Asia will restore ‘the whole of East and Southeast Asia to the Confucian civilisational tradition’.