The United States, people around the world say, was founded by Puritans. The Puritan colonists were inspired by ‘the magnificence of leading an exodus of saints to found a city on a hill [my emphasis], for the eyes of all the world to behold.’

Those are the words of Perry Miller, the 20th century’s pre-eminent scholar on the subject, interpreting John Winthrop, the first governor of Massachusetts, and author of this undying metaphor. Miller believed that Winthrop was ‘preternaturally sensing … the promise of America’. Politicians from Jack Kennedy to Ronald Reagan have exploited Winthrop’s image for their own visions of the promise of America, as have countless op-ed columnists and historians. It’s difficult to find an American history textbook today that does not claim that Winthrop spoke these words in a shipboard sermon to his fellow colonists crossing the Atlantic in 1630. But it’s not true.

Winthrop’s detailed diary of the ocean crossing never mentions delivering a lengthy address to his fellow passengers. Most of them were spread out across the seas on 10 other ships, well out of earshot. We have very little evidence that anyone who participated in the colonisation of New England ever heard of, or ever made reference to Winthrop’s ‘city upon a hill’ metaphor, which was a common image from the Sermon on the Mount. The only existing copy of this text – ‘A Modell of Christian Charity’ (not in Winthrop’s hand) – wasn’t discovered until the 1830s. The document strongly indicates that it was written for investors and future colonists still in England, not for shipmates on an ocean voyage. Its disappearance from the historical record for two centuries suggests how slight an impression it made at the time.

What’s more, the idea of an ‘exodus of saints’ to found an exemplary colony to reform the world wasn’t distinctive to New England. Many colonies shared similar goals. Virginia’s founders imagined they would solve England’s poverty and population problems while bringing Christianity to Native Americans. William Penn’s Quaker colony would be a city of brotherly love. Other colonising ventures, from Avalon (the mystical island of Arthurian legend) to Eleutheria (Greek for ‘freedom’) to Providence, shared these transformational aspirations, and most of them failed. What has made Boston and New England a distinctive society since the 17th century was something more mundane: political economy.

By 17th-century European standards, the founders of Massachusetts had radical ideas about governance and the allocation of resources. Unlike many other colonising ventures, their leadership wasn’t drawn from England’s aristocracy. Massachusetts colonists came from the middling sorts: merchants, farmers, artisans, lawyers and, of course, clergymen. They believed that honest respectable men could govern themselves in both church and state, without bishops or lords and, bending the rules of the charter granted by King Charles I in 1629, Massachusetts launched an experiment in self-government.

Their churches were gatherings of like-minded believers who covenanted among themselves and elected their own ministers, appointed by neither pope nor king. Their towns were deliberately egalitarian, dispensing land among all the colonist families, each according to their abilities and needs, and every family had a say in town government. Male household heads and church members chose the colony-wide representatives and officers, including the governor, in annual elections.

But without a vigorous economy to sustain them, the Puritans’ republican experiments would have died on the vine. It was Boston’s political economy, fashioned by and for these middling, property-owning migrants to sustain their social vision, that gave the region its distinctive character.

To understand New England’s contribution to, and its critique of, American history, it’s best to lay aside mythic notions of divine inspiration or American exceptionalism. The American nation is in no way New England writ large. The region’s political economy, which long outlived its Puritan origins, diverged in significant ways from the other colonies. This gave New England a critical distance from and perspective on the development of the nation that these colonies eventually became.

For overseas colonies to be viable, they had to produce something of high value in European markets. The cost of oceanic transportation in the age of sail meant that it was pointless to ship cheap goods long distances – shipping costs would eat up any meagre profits. The silver and gold that Spanish conquistadors found in central and south America, or the sugar and tobacco produced by Caribbean and southern plantations fit the bill. These commodities were rare, addictive and highly desired in Europe. The Puritan colonists found no comparable staple agricultural products or natural resources in New England, though not for want of trying. If sugar cane could have been grown in New England’s cold climate, or if they had found gold in the Berkshires, the Puritans would have exploited these opportunities. European imports were essential to any colony’s survival, and colonists had to produce something that would pay for them.

The import needs of Massachusetts were higher than most, for, in addition to the clothing, tools and other amenities of life that every colony imported, the Puritans were at the cutting edge of early modern intellectual culture. Their ideal society would be literate and learned, connected to Europe’s universities and seminaries by paper and ink, books and print. The high-value commodities needed to pay for these imports proved elusive. Not that New England was poor. The colonists quickly learned, with assistance from the region’s Indigenous peoples, to produce abundant food supplies. The region’s forests yielded all the fuel and building materials they could want. Subsistence was relatively easy.

But New England’s colonists hadn’t uprooted themselves and crossed the ocean in pursuit of mere subsistence – they hadn’t been poor in England. Yet there was no market in England for the cheap stuff they could produce. By the early 1640s, migration to the colony slowed and then stopped. English merchants might no longer be willing to send ships to Boston because they would find so little there to fill their hulls for a return voyage. Colonists began to return home. The Massachusetts Bay Colony was in danger of joining a long line of failed colonies.

Boston built itself as a quasi-autonomous city-state with an expansive regional hinterland

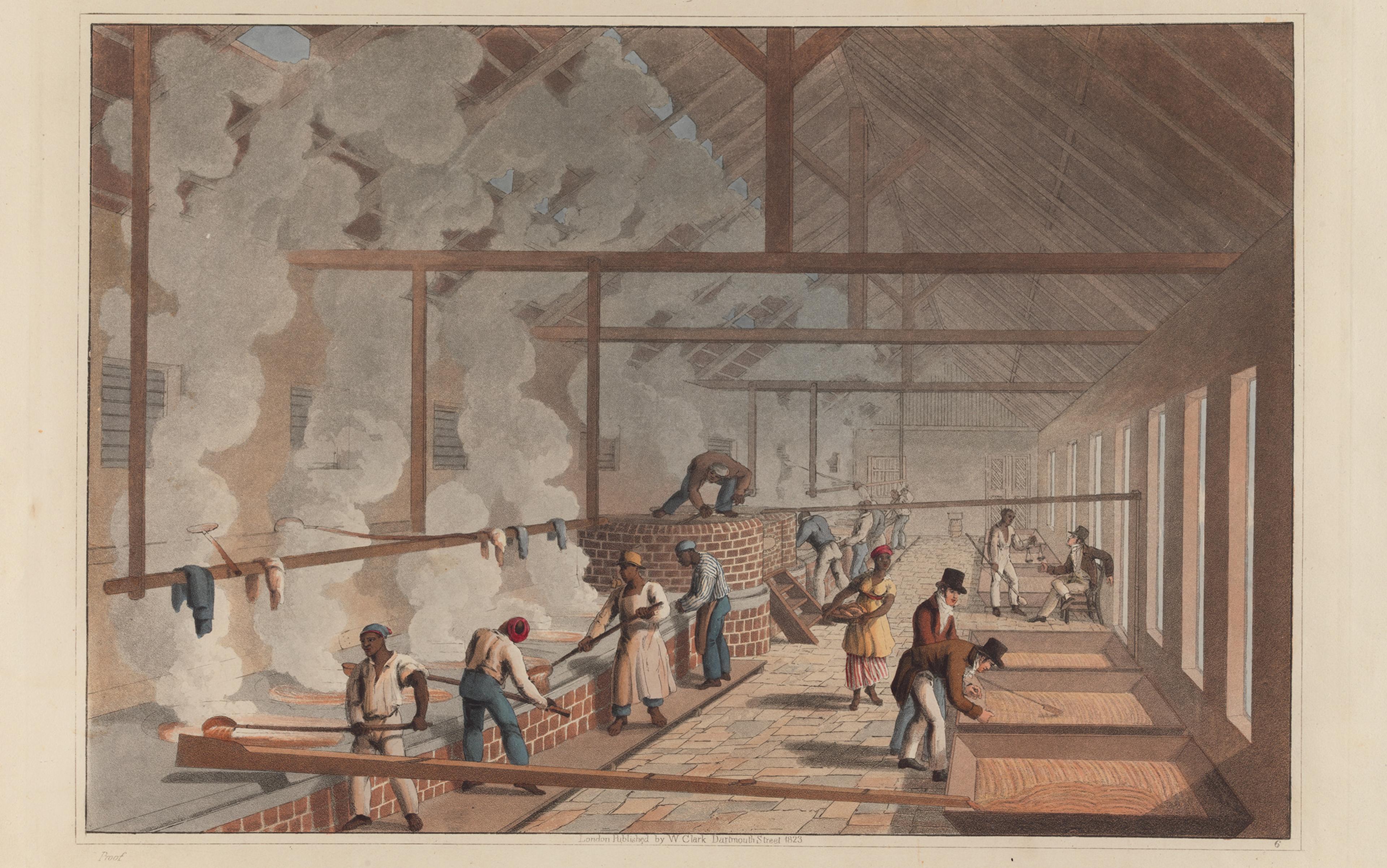

Financial salvation came through the Caribbean, more than 2,000 miles away. In the 1640s, the English colony of Barbados began a rapid transformation to sugar production. Barbadians purchased ever larger numbers of African labourers to produce this valuable crop. The island’s limited arable land was quickly given over to sugar cane, its trees cut down for construction and fuel, while its population skyrocketed. Profits from sugar were so great that the plantation owners of Barbados were willing to pay high prices for food for their enslaved labourers and themselves, timber for sugar mills, housing, fuel and barrels to export their sugar. Selling to Caribbean planters, Boston’s merchants found a market for things that New England farmers and fishermen could easily produce. They could then trade West Indian sugar in London for manufactured goods.

With this trade network in place, New England saw tremendous growth in colonial settlement. From the initial hearth centred on Boston in Massachusetts Bay, a narrow slice of territory defined by the 1629 charter, migrants spread out and founded new colonies along New England’s southern coast at New Haven, Connecticut and Rhode Island, and to the north in New Hampshire and Maine. The small Plymouth colony joined this larger system as well. Boston’s leaders organised a political alliance (the New England Confederation or United Colonies), its clergy promoted a common form of church governance across the region supplied by the graduates of Harvard College, and merchants in Boston linked the region’s produce to Atlantic markets.

No other colonial region in Britain’s empire developed in the way that Boston built New England, by hiving off new colonies in the image of the original founder. Boston built itself as a quasi-autonomous city-state with an expansive regional hinterland. Its political economy was a hybrid within the imperial system. Like other colonies, New England depended on the English homeland for manufactured goods, but unlike other colonies it produced no valuable staple crop to ship directly to the metropolis. Instead, Boston competed with the homeland’s merchants for the carrying trade of other colonies, which violated prevailing ideas of the purpose of colonies. New England also claimed a greater degree of political autonomy than the staple-producing colonies, also not part of any imperial plan.

New England’s founding ideals for an egalitarian and self-governing polity failed when it came to the region’s native people. Massachusetts made greater efforts than any other English colony to introduce Christianity to Native Americans and encourage them to adopt English ways of life. But over time the insatiable land hunger of the growing colonist population overwhelmed these efforts at cultural integration and replaced them with the violent dispossession typical of other colonies as well. In this sense, New England was not different from other regions.

At the same time, New England’s political economy made the burgeoning city-state dependent on the brutal system of racial slavery that drove the plantation complex. Slavery lay at the heart of the emerging world of American colonisation. Enslaved labour was responsible for producing most of the valuable commodities shipped across the ocean. The richest colonies of every European empire relied heavily on enslaved labour, whether Indigenous or African. The economy that colonial New England developed was a curious hybrid, reliant on trade with slave-based economies, yet itself without plantation agriculture.

The percentage of enslaved workers in the New England colonies was a tiny fraction of what it was in Carolina or Jamaica, Saint-Domingue or Brazil. Slavery had no explicit part in Boston’s founders’ economic plans for their colony. Yet, from the very beginning, New England colonists enslaved Indigenous and African people in ways they didn’t other English people or Europeans. Bound labour and servitude were common in English society, from apprenticeships to indentured service. Families routinely put their teenaged children out to service in other households. But lifelong hereditary servitude for English workers was unknown, and the murderous labour regimes of the sugar plantations were reserved for African or Indian enslaved workers. The enslaved in New England were spared the latter, but not the former. With the establishment of trade routes to the slave-plantation colonies, and soon to West Africa as well, the slave trade and the importation of enslaved labour became a minor but steady aspect of New England’s economy.

They liked to keep the savagery of slavery at a distance, while profiting from trade with the slave plantations

From the commencement of trade relations with the Caribbean, the tension between the brutality of racial slavery and the egalitarian, self-governing ideals pursued by New England’s Puritans was obvious. The problem of slavery became a recurring theme in the city’s public discourse. As early as the summer of 1645, with the Barbados trade just beginning, Emmanuel Downing, a leading member of the Massachusetts Council, wrote to his brother-in-law John Winthrop, suggesting the potential for slavery as a source of commercial profits and as a labour force for Massachusetts.

Downing proposed that New England Indians captured in ‘just wars’ might be exchanged for African slaves (‘Moores’ he called them), ‘[a]nd I suppose you know verie well how wee shall maynteyne 20 Moores cheaper then one Englishe servant.’ Winthrop and his fellow colonists decided otherwise, and chose not to follow the Barbadian model. They preferred in the main to keep the savagery of slavery at a distance, while profiting from trade with the slave plantations.

However, even at this geographical distance, slavery continually generated turmoil and public arguments in Boston. Over time, Boston and New England would become centres of antislavery and abolitionist activity – but not because the region was innocent of slavery’s crimes. Rather, the hybrid nature of its political economy – as a dependent colony proclaiming its independence, and as an egalitarian society deeply enmeshed with slavery – made Boston and New England a natural place for criticism of slavery to emerge. Contrary to popular narratives of inevitable progress, the arguments over slavery worsened and the conflicts grew more intense as slavery developed across the centuries. With political, economic and technological change, it became ever harder for Boston to keep slavery at a distance – its encroachment undermined the values of autonomy and egalitarianism that were also important New England ideals.

In the mid-1640s, as Downing contemplated the Barbados model for Massachusetts, two Boston mariners, Captain James Smith and his first mate Thomas Keysar, sailed in the ship Rainbow on the colony’s first trading voyage to West Africa. There they met up with London-based slave traders, and became accomplices in an assault. The London slavers, claiming that they had ‘been formerly injured by the natives’, kidnapped a number of Africans. When the natives protested, the slave traders ‘assaulted one of their Townes and killed many people’.

After a meandering return trip by way of the West Indies, Smith and Keysar arrived in Boston. They sold two kidnapped Africans who remained in their possession, then took each other to court to sort out their commercial disputes. In October 1645, the court took an extraordinary step. On the advice of Boston’s clergy, the judges felt that they couldn’t punish Smith and Keysar for ‘the slaughter committed’ in Africa, ‘seeing it was in another Countrye, & the Londoners pretended a just revenge’. But with respect to the kidnapped Africans, ‘the magistrates tooke order to have those 2: sett at Libertye, & to be sente home.’ The court held that the slaves’ captivity was clearly not the result of a just war (a scriptural standard for lawful enslavement), but was rather an instance of ‘manstealing’, and the Africans were returned to their homeland. The oceanic distances of the Atlantic economy ordinarily hid the violence of enslavement’s origins from the ultimate purchasers of slave labour. But when New Englanders themselves were present at the scene of the crime, it couldn’t be ignored.

By 1700, half a century later, a steady trickle of African enslaved workers had arrived in Boston, amounting to roughly 400 people, about 6 per cent of the town’s population. The city’s merchants had built Boston’s growing prosperity on their capacity to supply the sugar islands with everything they needed, including African slave labour. The year 1696 saw the end of England’s Royal Africa Company’s monopoly on the slave trade, greater opportunity for Boston merchants trading in Africa, and more enslaved people in Boston. Amid these pressures, Samuel Sewall, a Boston merchant and judge, addressed the problem of slavery. He was prompted by the case of an enslaved worker named Adam, who demanded the freedom that his master had once promised. Legally, Judge Sewall found it impossible to follow the precedent of 1645. Legislation and customary practice of the preceding half-century had established slave-owners’ rights. Adam’s owner was John Saffin, Sewall’s fellow justice on the Massachusetts Superior Court and his chief antagonist on this question. Barred from granting Adam his liberty, Sewall rendered a verdict in the court of public opinion by attacking in print the legitimacy of the slave trade and slave-holding in a Christian commonwealth.

View of the Long Warf & port of the harbour of Boston in New England, America by R Byron circa 1754. Courtesy Digital Commonwealth/Massachusetts Collections online

In The Selling of Joseph (1700), one of the earliest antislavery publications in the English-speaking world, Sewall argued that the slave trade was legalised manstealing. No potential good that might come of the practice, even the conversion of enslaved people to Christianity, could justify this evil. According to Sewall, human freedom couldn’t be equated with money: ‘There is no proportion between Twenty Pieces of Silver, and LIBERTY.’ Nor could faith be placed in claims that faraway just wars produced marketable human commodities: ‘Every War is upon one side Unjust. An Unlawful War can’t make lawful Captives.’ Every enslaved African brought to Boston eroded the pretence that the crime of slavery could be kept at a distance.

Wheatley audaciously asserted that an enslaved person could be a voice for New England’s liberty

Legally, Sewall lost but his debate with Saffin bore other fruit. Sewall and other religious figures saw the growing reach of empire as a way to ameliorate the conditions of enslaved people, to promote baptism and conversion, and, at least in Massachusetts, to ensure the lawfulness of slave marriage and prevent slavery’s worst abuses. If Africans, like the biblical Joseph, were going to be stolen and sold into slavery, then at least evangelical Protestants could ensure that the blessings of Joseph would come to them as well. Sewall’s pamphlet did nothing to stem the tide of British expansion in the slave trade. But it launched a conversation that challenged the absolute commodification of enslaved people and began to imagine an empire without slavery, reformed from within by the force of Christian charity.

Seven decades later, Phillis Wheatley, an enslaved Bostonian, gave poetic form to Sewall’s arguments. In publishing Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (1773), Wheatley audaciously asserted that an enslaved person could be a voice for New England’s liberty. Although her poems paid respects to leading figures of Boston, New England and the British empire, including an ode to King George III, Wheatley represented herself addressing figures such as the Earl of Dartmouth, Britain’s secretary of state for the colonies. Wheatley’s ode ‘To the Right Honourable William, Earl of Dartmouth’ demanded that he honour New England’s claim to self-governing autonomy, then endangered by parliamentary legislation.

Portrait of Phillis Wheatley. Courtesy the Met Museum, New York

As Wheatley demanded freedom for New England, the irony of her own enslavement was not lost on her. To resolve this tension in her ode to the Earl of Dartmouth, she assumes the part of the biblical Joseph, sold into Egyptian slavery, but raised up by his remarkable abilities to become Egypt’s effective ruler. Wheatley accepts that, although her enslavement, like Joseph’s, was a crime, it brought her spiritual redemption in Christian New England. On this basis, she refuses to allow her legal status or racial difference to separate her from New England’s birthright of British liberty.

Enslavement gave Wheatley heightened awareness of the value of liberty, but like the mature Joseph thinking of the sorrows of his father Jacob, it’s not her own suffering that moves her, but that of her bereaved parents: ‘What pangs excruciating must molest,/What sorrows labour in my parent’s breast?’ These feelings cause her to ‘pray/Others may never feel tyrannic sway’. By refusing the part of the victim, Wheatley denies the power of the crime of manstealing to determine her identity. Her poetry makes manifest the truth of Sewall’s maxim: that there’s no proportion between 20 pieces of silver and liberty.

Wheatley’s literary performance, powerful as it was, came at an untimely moment. By the 1770s, a serious antislavery movement had appeared in Britain. On a visit to London accompanying her owner, John Wheatley, she was feted by Granville Sharp and the Countess of Huntingdon, two of its leading lights. The Wheatley family thereupon granted her freedom. But, at that moment, American colonists’ faith in Britain as protector of their liberties was eroding – the Boston ‘Tea Party’ took place only three months after Wheatley published her poems. The ensuing revolution broke Boston’s ties with the leaders of Britain’s antislavery movement, including Loyalists such as the Wheatley family, whose fortunes the rebellion destroyed. Phillis Wheatley was left without support or patronage in a ruined city. Ruined, but Boston was now independent of British authority, seemingly in possession of the autonomy it had always coveted.

Newly independent Massachusetts followed the logic of Wheatley’s poetry – abolishing slavery in the early 1780s. To defend its fragile independence, Massachusetts required union with other states, states that would reject the logic of Sewall and Wheatley. By ratifying the US Constitution of 1787, Massachusetts joined a government often dominated by plantation masters, which had not been the case under British rule. From this point forward, the autonomy Boston had built a city-state to sustain was gradually undermined by the political and economic power of the new United States.

By the 1820s, the institution of slavery had withered away within New England. The region’s economic reliance on slavery, however, had shifted from the Sugar Islands to the Cotton Kingdom. Boston merchants, scarred by Thomas Jefferson’s trade embargo and James Madison’s war against Britain, invested their capital in automated cotton textile production, a hugely profitable enterprise that nonetheless entwined the region’s economy with the explosive growth of slavery across the American south. David Walker, a free Black man, moved from Carolina to Boston in the 1820s and became a dealer in secondhand clothing. In 1829, he published his Appeal … to the Coloured Citizens of the World, which inaugurated a quarter-century of intensified debate over the city’s relationship to slavery.

As Sewall and Wheatley had, Walker’s Appeal once again put slavery in a biblical perspective, but his vision widened beyond the US. While Sewall had denounced the ‘selling of Joseph’ and Wheatley had assumed the position and power of Joseph in her poetry, Walker compared the Egyptians’ relatively benign treatment of the children of Israel and the Pharaoh’s empowerment of Joseph with white Christian America’s treatment of Africans: ‘I only made this extract [from Genesis] to show how much lower we are held, and how much more cruel we are treated by the Americans, than were the children of Jacob, by the Egyptians.’ The creation of the US had short-circuited Wheatley’s hopes that enslaved people would receive the benefits of Joseph under Britain’s benevolent empire of liberty. King Cotton, in the US South, was not so benevolent.

Where Wheatley had believed that the Christian liberty promoted by New England would reform the British empire, Walker claimed that evangelical Protestantism had been perverted by the Pharisees of white American Christianity. His Appeal proclaims that the ‘Coloured Citizens of the World’ are the possessors of true Christianity, that they alone can bring the kingdom of God to all nations, and that, as a free Black Christian, Walker can be a full citizen only in this community; free Blacks in America, even in cities like Boston where the institution of slavery had been abolished, are still only partially free, so long as they remain under the dominion of the US. The Appeal aimed to rouse those of African descent in America from their subservience, and to claim a birthright equal to that of white Americans.

To spread his revolutionary pamphlet beyond Boston, Walker relied on his commercial contacts in the Atlantic seafaring community. As a used-clothing merchant, Walker would enclose copies of his Appeal in the linings of cheap garments, made in New England textile mills from cotton produced by enslaved people. Through the clandestine efforts of dock workers, ship stewards and sailors, the message of resistance could be distributed in southern seaports. After Walker’s untimely death in 1830, a growing portion of Boston’s antislavery community embraced his radical position. Leading abolitionists began to inveigh against a complacent American Christianity and the ‘covenant with hell’ that constituted the US constitution. The ground was being laid for violent conflict within Boston, precipitated by the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.

While the war brought the defeat of slavery, it also solidified and enhanced the power of the nation-state

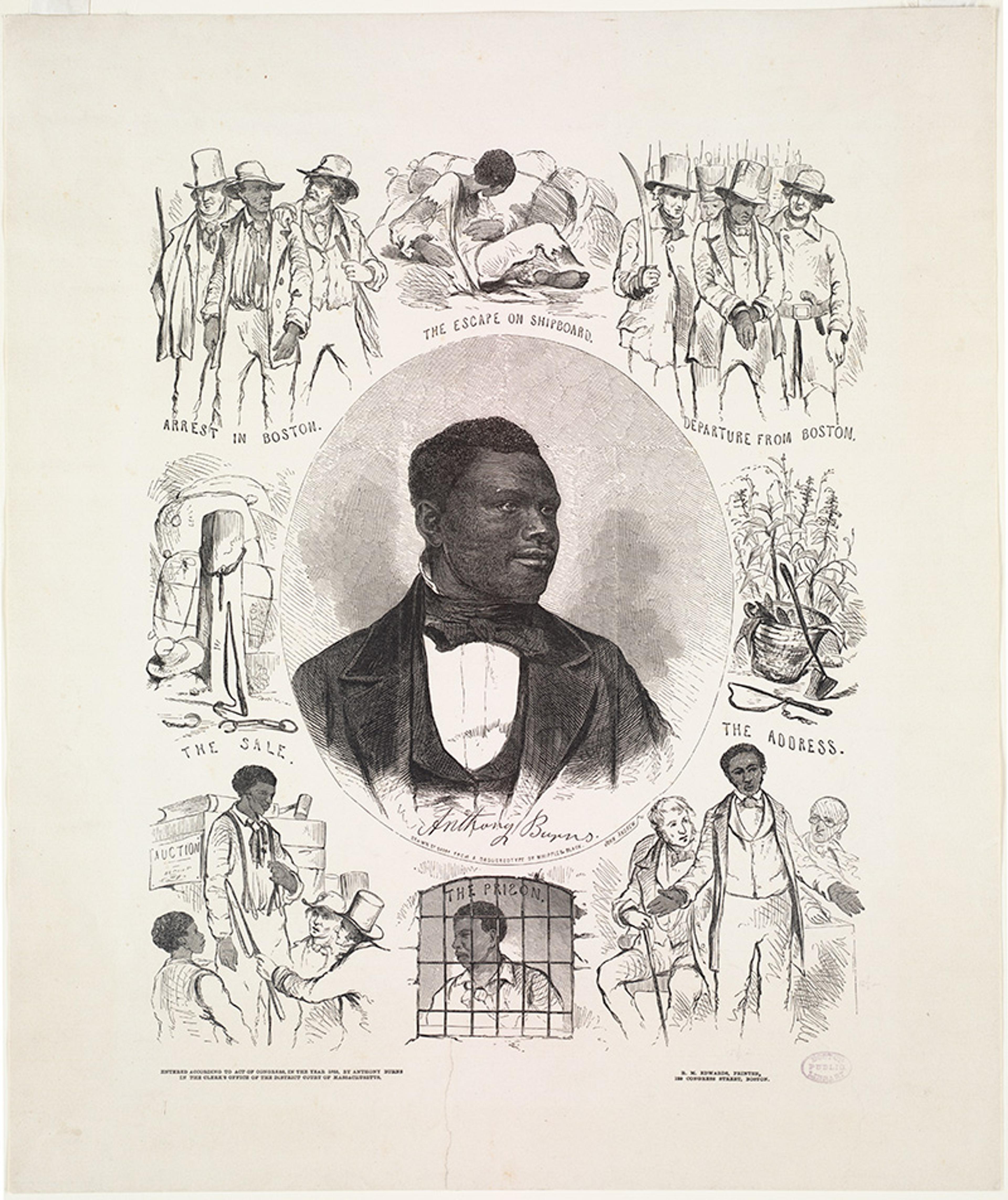

In 1854, Anthony Burns, an escaped slave from Virginia who had fled to Boston as a stowaway on a ship, was arrested by US marshals. In 1645, Boston courts had confronted the slave kidnapping and violence that had taken place in Africa, and the Boston slaveowners who claimed the right to own human property. In Burns’s case, the kidnapping and violence took place in Boston, and slaveowners waited from afar to see whether their slave would be shipped back to them. In 1645, Boston’s clergy had cautioned against entering the bonds of empire and the trafficking in human souls, and the court, heeding their advice, returned the slaves. In 1854, radical ministers denounced Boston’s ties with the US slave empire, while Burns’s defenders contemplated the possibility that they might have to buy him to prevent his return to Virginia.

Print showing a portrait of the fugitive slave Anthony Burns. Courtesy Digital Commonwealth/Massachusetts Collections online

In the end, the US attorney blocked the sale of Burns, as slave purchases were against the law in Massachusetts. And the courts were denied the power to free Burns, for, under the Fugitive Slave Act, judges could determine only the identity of the person in question, not whether that person was wrongfully enslaved. Despite violent protests of abolitionist crowds that left one of Burns’s jailers dead, the US marshals, supported by US marines with horse-drawn artillery, marched Burns from the court house down State Street to the waterfront and onto the revenue cutter that would return him to slavery in Virginia.

The rendition of Burns caused some of Boston’s industrial leaders to question the compromises they had been making. In the words of the textile magnate Amos A Lawrence: ‘We went to bed one night old fashioned, conservative, Compromise Union Whigs, and waked up stark mad Abolitionists.’ For those who already were abolitionists, Burns’s rendition proved that Boston was under the dominion of the Cotton Kingdom and subject to its demand for tribute. Theodore Parker, a Boston Transcendentalist minister and grandson of the militia captain who had stood up to the Redcoats on Lexington Green in April 1775, put it this way: ‘there is no Boston to-day. There was a Boston once. Now, there is a north suburb to the city of Alexandria; that is what Boston is. And you and I, fellow-subjects of the State of Virginia.’

Parker’s complaint that the old Boston was gone rang true. The city and region were no longer masters of their own economy. Boston in the 1850s was badly divided, segregated in racial and ethnic terms, and between rich and poor. The slavery issue roiled its politics. Mobs of well-dressed Bostonians whose employment depended on the cotton interest attacked abolitionist speakers, white or Black. The nation’s descent into Civil War replicated across the Union the divisions that afflicted Boston. And while the war brought the defeat of slavery, it also solidified and enhanced the power of the nation-state, foreclosing at last the possibility of an autonomous city-state of the sort Boston once was.

Vestiges remain to this day of that former New England, visible for instance in the region’s continuing commitment to education, one example of its willingness to tax itself more vigorously for the sake of public goods and social equity. But it’s essential to remember that New England’s distinctive identity over its first two centuries, its pursuit of egalitarian self-government among its own people, rested on its capacity to keep slavery, the most violent and exploitative aspect of the nascent Atlantic capitalist economy, at a distance, while simultaneously profiting from it. In the end this proved impossible to sustain, and the region’s complicity with this system overwhelmed its desires for autonomy and equality.

Despite the fact that Winthrop’s ‘city upon a hill’ metaphor has become a nationalist slogan, the modern US is by no means early New England writ large. New England was always an outlier among Britain’s colonies, and it remained so in the early years of the US, which explains why it so often served as the conscience of the nation, a critic of its dominant trends. Yet the downfall of the city-state of Boston provides a cautionary tale. In the interconnected world that Boston’s overseas merchants pioneered, no commonwealth can sustain true autonomy or equality by the exploitation of outsiders, whether within or without its borders.