In 1678, a Chaldean priest from Baghdad reached the Imperial Villa of Potosí, the world’s richest silver-mining camp and at the time the world’s highest city at more than 4,000 metres (13,100 feet) above sea level. A regional capital in the heart of the Bolivian Andes, Potosí remains – more than three and a half centuries later – a mining city today. Its baroque church towers stand watch as ore trucks rumble into town, hauling zinc and lead ores for export to Asia.

Elias al-Mûsili – or Don Elias of Mosul, as he was known – arrived in 17th-century Potosí with permission from Spain’s Queen Regent, Mariana of Austria, to collect alms for his embattled church. Potosí silver, Don Elias believed, would stave off the Sunni Ottomans and Shiite Safavids who battled for control of Iraq, periodically blasting Baghdad to smithereens with newly scaled-up gunpowder weapons. Just as worrisome to Don Elias were fellow Christians, schismatics with no ties to Rome.

The great red Cerro Rico or ‘Rich Hill’ towered over the city of Potosí. It had been mined since 1545 by drafted armies of native Andean men fuelled by coca leaves, maize beer and freeze-dried potatoes. When Don Elias arrived a century and a quarter later, the great boom of c1575-1635 – when Potosí alone produced nearly half the world’s silver – was over, but the mines were still yielding the precious metal.

By 1678, native workers were scarce and the output of the mines dwindling. Yet in the city’s royal mint, Don Elias marvelled at piles of ‘pieces of eight’, rough-hewn precursors of the American dollar, fashioned by enslaved African men. He saw them ‘heaped on the floor and being trampled underfoot like dirt that has no value’. For a long time, Potosí’s medieval technologies kept producing fortunes, if on a smaller scale.

On Potosí’s main market plaza, indigenous and African women served up maize beer, hot soup and yerba mate. Shops displayed the world’s finest silk and linen fabrics, Chinese porcelain, Venetian glassware, Russian leather goods, Japanese lacquerware, Flemish paintings and bestselling books in a dozen languages. Votive African ivories carved by Chinese artisans in Manila were especially coveted by the city’s most pious and wealthy women.

Pious or otherwise, wealthy women clicked Potosí’s cobbled streets in silver-heeled platform shoes, their gold earrings, chokers and bracelets studded with Indian diamonds and Burmese rubies. Colombian emeralds and Caribbean pearls were almost too common. Peninsular Spanish ‘foodies’ could savour imported almonds, capers, olives, arborio rice, saffron, and sweet and dry Castilian wines. Black pepper arrived from Sumatra and southwest India, cinnamon from Sri Lanka, cloves from Maluku and nutmeg from the Banda Islands. Jamaica provided allspice. Overloaded galleons spent months transporting these luxuries across the Pacific, Indian and Atlantic oceans. Plodding mule and llama trains carried them up to the lofty Imperial Villa.

Potosí supplied the world with silver, the lifeblood of trade and sinews of war – and as Don Elias knew, the surest means to propagate the Roman Catholic faith. In turn, the city consumed the world’s top commodities and manufactures. Merchants savoured the chance to trade their wares for hard, shimmering cash. The city’s dozen-plus notaries worked non-stop inventorying silver bars and sacks of pesos, loaded onto grumbling mules for the trans-Andean trek to the Pacific port of Arica or for the much longer four- to six-month haul south to Buenos Aires. In the rainy season rivers swelled, and in the dry season livestock died of thirst between scant watering holes.

Mule trains returning from the Pacific brought merchandise and mercury, the essential ingredient for silver refining. Most mercury came from Huancavelica in Peru, but the Spanish Habsburgs also tapped mines in Almadén (La Mancha) and Idrija (Slovenia). From Buenos Aires came slavers with captive Africans from Congo and Angola, transshipped via Rio de Janeiro. Many of the enslaved were children branded with marks mirroring those, including the royal crown, inscribed on silver bars.

Soon after its 1545 discovery, Potosí gained world renown, but central European mines also flourished after 1450, faltering only before Potosí hit its stride in the 1570s. Silver was discovered in Norway in the 1620s, but not enough for export. The Iwami silver mines of southwest Japan, developed in the 1520s, exported substantial silver via the port of Nagasaki after 1570, first by the Portuguese and then, between 1641 and 1668, by the Dutch. The main exporters of Japanese silver however were the Chinese. Scholars dispute the numbers, but Iwami was not quite another Potosí.

Potosí, as Don Quixote proclaimed, was the stuff of dreams

As early as the 1530s, Mexico exported silver too, and considerable amounts of it. Yet Mexico’s many mining camps – Zacatecas, Guanajuato, Taxco, Pachuca, Real del Monte and the namesake San Luis Potosí – peaked only after 1690. In the 18th century, the Mexican peso or ‘pillar dollar’ took the world by storm. Even in the Andes of South America there were other silver cities (or towns) besides Potosí, including Oruro and Castrovirreyna in Peru. But no silver deposit in the world matched the Cerro Rico, and no other mining-refining conglomeration grew so large. Potosí was unique: a mining metropolis.

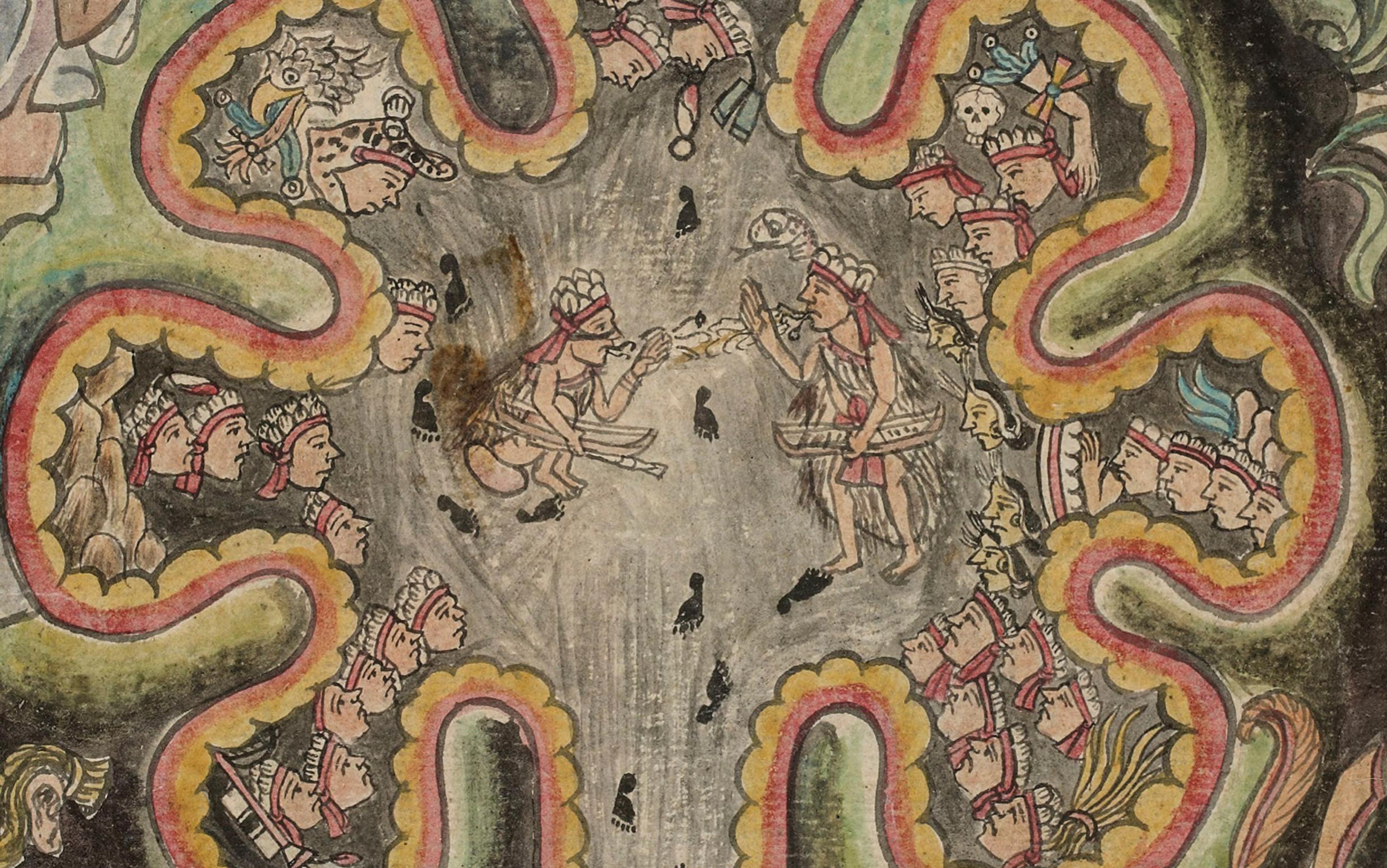

Thus Don Elias, like others, made the pilgrimage to the silver mountain. It was a divine prodigy, a hierophany. In 1580, Ottoman artists depicted Potosí as a slice of earthly paradise, the Cerro Rico lush and green, the city surrounded by crenellated walls. Potosí, as Don Quixote proclaimed, was the stuff of dreams. Another alms seeker, in 1600, declared the Cerro Rico the Eighth Wonder of the World. An indigenous visitor in 1615 gushed: ‘Thanks to its mines, Castile is Castile, Rome is Rome, the pope is the pope, and the king is monarch of the world.’ A 1602 Chinese world map identified the Cerro Rico as Bei Du Xi Shan, or ‘Pei-tu-hsi mountain’.

For all its glory, Potosí was also the stuff of nightmares, a diorama of brutality, pollution and crime. What Don Elias might not have known in 1678 was that Potosí’s reputation – and with it the Spanish Empire’s – had a generation earlier suffered mightily. In 1647, amid royal bankruptcy, King Philip IV dispatched a former inquisitor to unravel a massive debasement scheme that had metastasised inside Potosí’s royal mint. The plot corrupted nearly every official within 1,000 miles. Even Peru’s viceroy was suspected of complicity. Potosí’s debased coins, mostly pieces of eight, hit world markets after 1638, and before long merchants from Boston to Beijing were rejecting Potosí coins. The fountain of fortune had become a poisoned well.

It took more than a decade to hunt down and punish the great Potosí mint fraud’s culprits and to restore the coinage to proper weight and purity. A new design debuted to signal the new coins, but winning back global trust in Potosí silver took decades. Into the 1670s, even as Don Elias took donations in exchange for sermons in Syriac, Sumatran pepper-growers balked at coins stamped with a ‘P’.

Like the Bernard Madoff scandal of the 2000s, the Potosí mint fraud of the 1640s tells an interesting if not universal story. Nobody wanted to admit that they had been deceived. For Spain’s King Philip IV, the mint fraud – an inside job – was a world-class embarrassment and a sign of the decline of his empire’s fortunes. The global flood of bad coins hurt everyone, rich and poor. Genoese, Gujarati and Chinese bankers suffered ‘haircuts’, merchants worldwide forfeited precious ties of crosscultural trust, and soldiers throughout Eurasia saw their pay halved or worse.

Almost a century before Don Elias visited Potosí, Viceroy Francisco de Toledo revolutionised world silver production. Toledo was a hard-driving bureaucrat of the Spanish empire – and he more than any single man transformed Potosí from a hardscrabble mining camp into a bona fide city. It was a colossal undertaking, but one suited to the ambitions of King Philip II, the first European monarch to rule an empire upon which the sun never set. Toledo reached Potosí in 1572, anxious to flip it into the empire’s motor of commerce and war.

By 1575, the viceroy had organised a sweeping labour draft, launched a ‘high-tech’ mill-building campaign, and overseen construction of a web of dams and canals to supply the Imperial Villa with year-round hydraulic power, all in the high Andes at the nadir of the Little Ice Age. Toledo also oversaw construction of the Potosí mint, staffed full-time with enslaved Africans. Its first coins were hoarded, higher in silver content than they were supposed to be, and overweight.

Toledo’s successes came with a steep price. Thanks to the viceroy’s ‘reforms’, hundreds of thousands of Andeans became virtual refugees (those who survived) and, in the search for timber and fuel, colonists denuded hundreds of miles of fragile, high-altitude land. Implementation of a new technology, mercury amalgamation, introduced from Mexico on the viceroy’s orders, fouled the region’s air and streams. The city’s smelteries belched lead and zinc-rich smoke, guarantees that its children would suffer lifelong stupefaction.

Environmental hazards multiplied as the city boomed, and with these ills came murderous social conflicts, vagabondage, sex-trafficking, gambling, political corruption and general criminality. Epidemics swept the city every few decades, culling the most vulnerable. How did people respond to this lawlessness and chaos? How could they live in such an iniquitous and foul place? In what might be termed the ‘Deadwood paradox’, bonanza brought out the worst in people even as it also provoked startling acts of liberality. It was, after all, the city’s generosity, its profligate piety, that brought Don Elias to Potosí, all the way from Baghdad.

The Habsburgs had discovered the magic formula for turning silver into stone

The Habsburg kings of Spain cared little about Potosí’s social and environmental horrors. Potosí silver, for them, was an addiction: deadly and inescapable. For more than a century, the Cerro Rico fuelled the world’s first global military-industrial complex, granting Spain the means to prosecute decades-long wars on a dozen fronts – on land and at sea. No one else could do all this and still afford to lose.

A steady flow of Potosí silver – or, rather, the promise of silver futures – rendered the Spanish Habsburgs’ otherwise absurd dreams possible. Then, all of a sudden, it didn’t. Even before the mint fraud of the 1640s, which helped bankrupt the crown, large quantities of Potosí silver slipped away, siphoned off by the empire’s friends and enemies alike: foreign bankers, contraband traders, pirates. At the same time, silver’s abundance stunted other parts of Castile’s internal economy. Some joked that the Habsburgs had discovered the magic formula for turning silver into stone.

The great Potosí bonanza, source of price disruptions, fiscal crises and costly building projects all over Europe, mostly fuelled commercial and imperial expansion in Asia. Throughout the 17th century, Dutch, English and French merchant-colonists, followed by a few intrepid Italians and Scandinavians, jockeyed with each other and with the embattled Spanish and Portuguese for a space at the great Asian table. All that Asia wanted, beyond tips on gun design, was silver. Europeans steered or inflected some of this pan-Asian trade and empire-building, but not most of it.

Often forgotten were the many thousands of Asian and African merchants and bankers based in Mombasa, Mocha, Mosul, Gujarat, Aceh, Makassar, Canton and many other port cities, including European-controlled Goa, Batavia, Madras, Macau and Manila. In the 17th century, these ‘country traders’, as Europeans called them, moved and lent more Potosí silver than all Europeans combined. Chinese diasporic trading communities in Southeast Asia alone controlled a large share of this global business.

Asian emperors were another matter. Mughals such as Akbar and Shah Jahān, or the Safavid Shahs Abbās I and II, or the Ottoman Sultans Murad III and IV, ruled tributary states whose size and diversity more than matched the empires of the Iberians. Northern Europeans, Dutch ambitions notwithstanding, were far behind. Just as the Spanish Habsburgs began squaring off against the French and English, the ‘gunpowder’ monarchs of the Middle East and South Asia scooped up satellite kingdoms and principalities, propelled to a degree by Potosí silver.

And what about China? As the Potosí mint fraud reverberated, the Ming Dynasty collapsed. The tipping point came in 1644, but the historic Qing takeover was hardly instantaneous. Both Qinqs and Mings spent massively as China’s economy shuddered from war and famine. Ming subjects scrambled for slivers of silver to ward off invading soldiers or to buy passage to freedom. Even a debased peso was a gift of heaven.

When Don Elias visited in the 1670s, Potosí had seen better days. But it was without qualification a global city, a site of suffering but also of wonder, a showcase of technological innovation and cultural sophistication. In the 1970s, proponents of dependency theory, most famously Eduardo Galeano in Open Veins of Latin America (1971), held up Potosi as the tragic exemplum of third-world underdevelopment, a hollowed-out periphery. Yet in its own day, Potosí was a recognised centre. A 1640 manual by Alvaro Alonso Barba, its great metallurgist, was translated and republished for centuries. Numerous painters, poets and playwrights made the city home. In the decades before the great mint fraud, potosinos challenged the king, proclaiming that he (and the world at large) needed them more than vice versa.

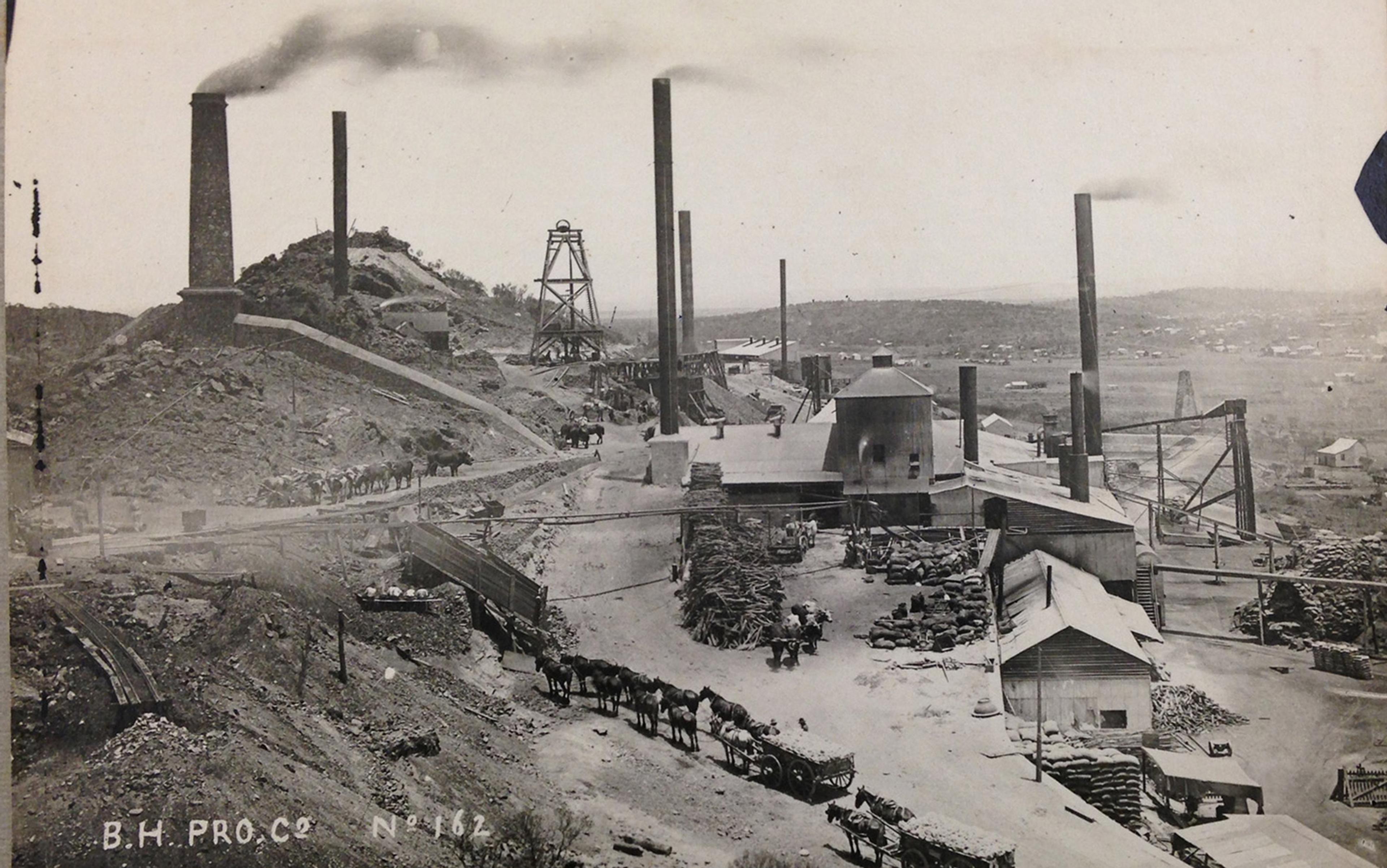

The end came not as spectacular implosion but as irreversible decline. Lower taxes and the imposition of a harsher labour regimen lifted silver production in the later 18th century, but the mines were deep and mercury expensive. Technological fixes failed. Simón Bolívar reached a beaten-down but jubilant Potosí in 1825, but British capitalists – close on the Liberator’s heels – could not revive the mines. It was local entrepreneurs and smallscale miners and refiners, many of them indigenous, who kept Potosí alive to the end of the 19th century using archaic but trusted technologies, including the methods of Barba.

By the time that the American historian Hiram Bingham visited the former Imperial Villa in 1909, Potosí had less than a 10th of the population it had boasted three centuries before. A colonial precursor to Bingham’s 1911 ‘discovery’ of Machu Picchu, the old Imperial Villa struck the professor as a silent spectre, not a typical US ghost town but rather a ‘super-sized’ object lesson in the vanity of Catholic Spain’s global ambitions. By this time, mineral rushes had helped to produce cities such as San Francisco and Johannesburg, but nothing quite compared for sheer audacity with the Imperial Villa of Potosí, a neo-medieval mining metropolis perched in the Andes of South America.

Today, almost 500 years after its discovery, Potosí’s Cerro Rico continues to supply the world with raw metals, a bit of silver and tin, but mostly lead and zinc. Half-processed ores wend their way through town and across the mountains and the Altiplano, to refineries in China, India, South Korea and Japan. The city has grown considerably in recent decades, now surpassing its colonial population (and severely straining its water supply). Has Potosí come full circle or is it stuck in the same rut? Will the sale of metallic mud to Asian manufacturers do more for ordinary folks than what was done by the silver-hungry Spanish, British or Yankees?

Potosí remains a globally connected city, a cog in the world economy, a regional magnet for migrants, a space for self-reinvention. Yet recalling its Habsburg heyday, the Imperial Villa of Potosí was famous not only for its mineral bounty but also for its artistic production, its political heft, its piety. Despite their own troubles, the city’s inhabitants gave Don Elias a small fortune in silver to fund his quixotic project in ‘Babylon’. Potosí also remained infamous for its pollution, its round-the-clock workingman’s horrors, its perennial violence, its corruption. Potosí was a mountain of silver that changed the world even as the world changed it. After five centuries of globalisation and exploitation, we can look back on this unique city’s history and ask what, in truth, it means to be ‘worth a Potosí’.