For the great majority of human history, we have been governed by sacred kings: individuals who claim that their right to rule depends not on their relationship with the people, but on their relationship with the divine.

If you want to know what sacred kingship might look like in the postmodern age, Thailand will give you an idea. The monarchy does not formally govern the country, which has for decades been characterised by a parliamentary democracy punctuated by military juntas. But it undoubtably carries considerable political potency. In May 1992, the last king, Bhumibol Adulyadej, defused a major political confrontation between pro-democracy protestors and the military by summoning the leader of the military junta, General Suchinda Kraprayoon, and his opponent Chamlong Srimuang, to be humiliated on national television. Kraprayoon and Srimuang crawled on their knees to King Bhumibol’s feet, where, on television before the nation, they received a scolding.

For most of the 20th century, it seemed that religion would recede from public life to a more private realm, or even disappear altogether. However, since at least the turn of the millennium, wherever we look, religion is asserting itself as a force in global politics. This can give the impression that little has changed; that religion has returned to play the same role in the political arena that it has always played. But that is not so: it is helpful to consider the Thai monarchy precisely because it is a partial exception to an important rule of the secularisation of governance. It gives us a sense of what it might look like if the form of sacred kingship that dominated most of human history was transported into the 21st century and given modern media technologies to play with.

In Thailand, the king’s image is everywhere, and it is venerated – backed up by some of the strictest lèse-majesté laws in the world. Perhaps the most sacred ritual of the royal calendar concerns the king and the jade statue of the ‘Emerald Buddha’, located in the temple of that name in the Grand Palace. Three times a year, the king changes the clothes of the statue to mark the start of each season and to ensure that its protection is extended to the kingdom as a whole.

When King Bhumibol died on 13 October 2016, the mourning extended to almost all areas of life. Some of the mourning symbolism connoted the experience of a power ‘blackout’, as many turned to wearing black (although white is the traditional colour of mourning). Shops switched off florescent signs and turned down music; some television channels were transmitted in black and white. For several weeks, an animation film projected against the high-end EM District mall displayed the late king in the vitality of his youth. In the film, King Bhumibol merged with a blinding light. He also walked into dry rural landscapes only for his presence to transform them into green, and then gold, blossoming fields. Mere metaphor? Perhaps. But consider the fact that Bhumibol means ‘strength of the land’, and that he held several patents for ‘royal rainmaking technology’ which is designed to manipulate the movements and forms of clouds. An ancient idea of fertility and cosmic potency has been rendered in modern digital technology.

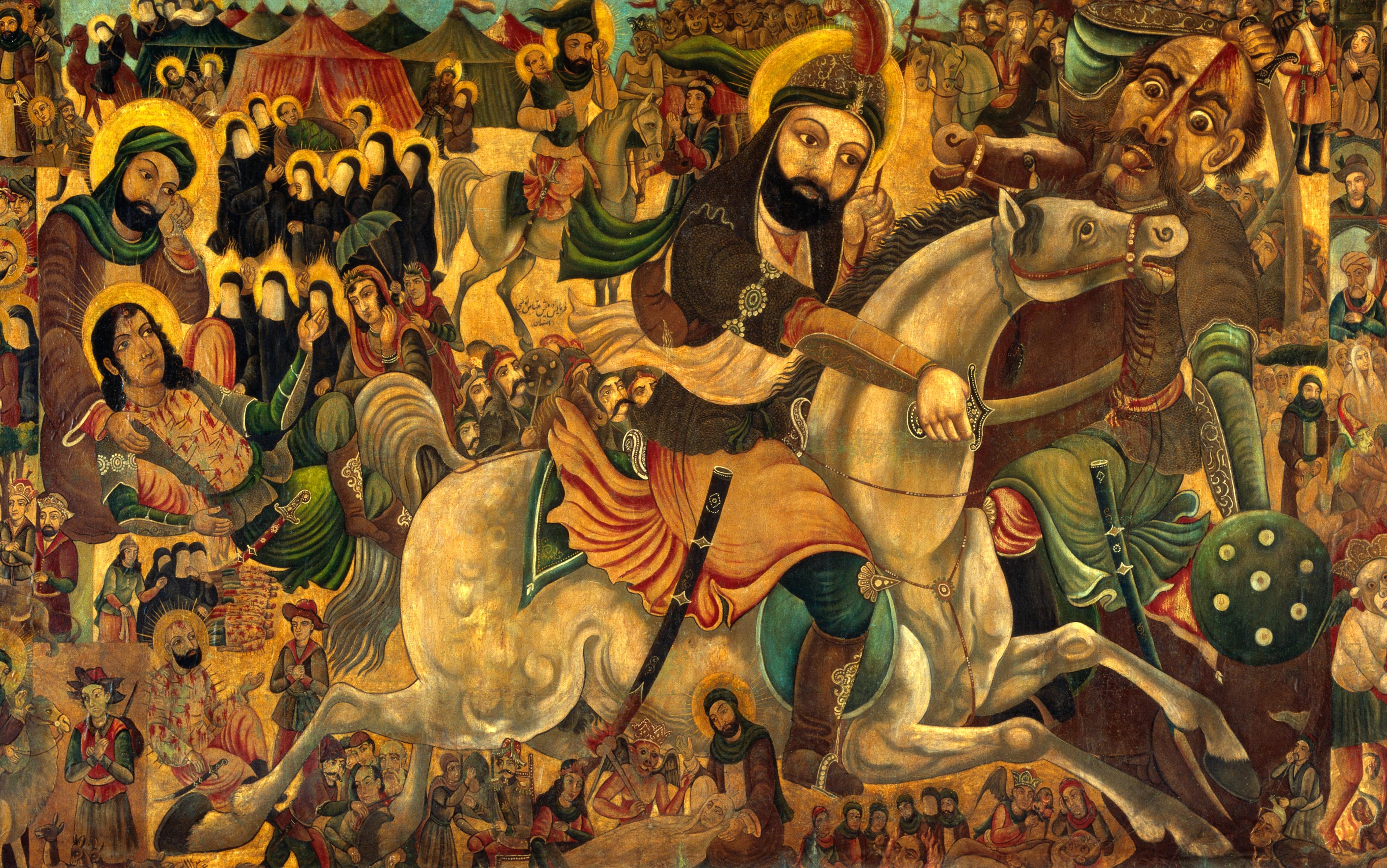

This is how authority was created in the pre-modern world. Chinggis Khan did not say: ‘I am the will of the people.’ He said: ‘God has made me the sole ruler of Earth.’ Chinese emperors ruled because they had the mandate of Heaven (not the mandate of their subjects). The Safavid rulers of Iran came to power as Sufi saints claiming to be the embodiment of divine truth and the incarnation of Muhammad’s son-in-law, Ali. Buddhist kings claimed to be bodhisattvas, iterations of the Buddha himself. For European monarchs too, such as Charles I of England, the fundamental justification for their authority lay in the ‘divine right of kings’.

Like modern political leaders, sacred kings claimed to bring their people great benefits: peace, order, prosperity. But their right to rule devolved from the divine; it did not rest on the will of the people. In many cases, sacred kings claimed to bring benefits not only through wise policies, but more directly through their unique access to supernatural forces. Quite independently of each other, different societies from Ancient Egypt to 18th-century Tonga arrived at the understanding that kings were essentially a means of regulating the powers of the cosmos for their benefit. This idea lay behind the urge to render them godlike by effacing their human and mortal nature and surrounding them with taboo and ceremony. Thus were they pushed up into the world of the gods in order to conduct business with them.

Sir James Frazer and A M Hocart, two of the founding fathers of anthropology, believed that kingship formed as a means of mediation with supernatural forces. It was, in this view, a ritual device that only later acquired political functions. This does not work as a general origin story of kingship, but it still conveys a significant insight. It turns upside down the Marxian notion that has become a kind of common sense, whereby the religious aura around kings was so much mystification designed to stop their subjects noticing their oppression. Undoubtedly, ambitious rulers did utilise religion in order to legitimise their authority; indeed, hard-headed rulers expended remarkable amounts of time and energy on establishing their religious credentials. But kings were also turned into sacred and magical objects by the hopes and projections of their subjects.

Some anthropologists have found evidence from parts of Africa that ritual efficacy could come before political efficacy. In Southern Sudan, for example, rainmaker specialists could become chiefs and kings – but this came with a worrying rider: that they might be punished and killed if they did not come up with the goods. There are clues that they tried to acquire actual coercive power – via firearms, for example – in order to protect themselves from the anger of their disappointed subjects. In the 1850s, a Bari king was beleaguered during a famine, for ‘despite his spells the rain did not come’: he faced down his angry subjects with a rifle. (When the drought came again for the third time, a French traveller in the 1860s was told: ‘We slit Nyiggilo’s stomach open and threw him into the river: he will no longer make fun of us.’)

Are such figures best described as kings, or rather as sorcerers, priests, fetishes? The ambiguity here is revealing. In fact, the association between kings and the control of the elements is widespread. In 17th-century Siam (Thailand), for example, one of the very few occasions in which the king was presented to the people outside the palace was for the ‘speeding of the outflow’ ceremony at the end of the monsoon period, in which he rode out on a barge and tapped the floodwaters with a fan to make them recede. In this way, the rice harvest would be secured.

Otherwise, the king of Siam was installed deep in his palace. He ate alone, like so many kings worldwide. As French missionaries and ambassadors discovered when they reached the court of King Narai in the 1680s, touching the king was deeply taboo. He could not receive anything by hand: it had to be taken draped under a parasol by the king’s pages, who would then give them to a higher rank of pages, who would in turn present it to the king in a golden bowl only at the end of a long handle, which they somehow held up while lying on the ground. Even pointing at anything he used would result in the mutilation of the finger. Any audience with the king involved lying prostrate, still and silent on the floor while the king appeared from a high window. The king spoke a special courtly language based on Khmer. No one was allowed to speak his name. The French might have thought they were quite used to royal pomp, coming as they did from the Versailles of the Sun King Louis XIV. But they had seen nothing like this. The missionaries began to realise that converting such a godlike being would not be quite so straightforward.

Such restrictions detached the king from the world of humanity, and placed him as an intimate of the gods. Worldwide, kings could be thought of as the descendants of gods, as their vessels, their hosts, their sons, brothers, and lovers. When Narai was consecrated, one of his titles was ‘Manifestation of the Eleven Dreaded Ones’, which signifies the Brahmanic gods who had come together to be reborn in him.

Mourning their chiefs, Hawaiians might knock out one or more of their front teeth or tattoo their tongues

Much of the ritual of kingship in Siam was inherited from the neighbouring Khmer kingdom, famous today for the huge temple complexes of Angkor created as a microcosm of the heavens on Earth. At the end of the 13th century, a Chinese ambassador stayed in Angkor for more than a year and wrote an account of it. He reported the story that every night the king ascended the steep steps of Phimeanakas, the state temple in the shape of a mountain in the middle of Angkor Thom, in order to couple with a naga (a nine-headed snake spirit) in the shape of a woman. The prosperity of the country depended on it. Some scholars discount this as rumour, but it is surely more intriguing as such – giving us a clue as to what kingship really signified in the popular imagination – and it echoes the origin myth of the Khmer as a union between powerful foreigners and indigenous, watery, serpentine spirits. Much of the symbolism shaping the sacred architecture of Angkor speaks of the king’s ability to harness the flow of water for the benefit of his subjects – both on a practical and a cosmic-supernatural level.

It is because of their cosmic responsibilities that kings presided over cults of human sacrifice in states as far apart as the Aztecs, the Dahomey in West Africa, or Hawaii. They were dispatching to the gods the most precious prize of all, in the hope that the gods would reciprocate by showering their blessings, allowing the crops to grow, the Sun to keep arriving each morning, and victory in the next battle.

Because the king lay at the centre not just of the political sphere but of the biological, social and cosmic worlds, his death presented a potentially bewildering rupture in the structures of life. Mourning their chiefs, Hawaiians might knock out one or more of their front teeth or tattoo their tongues, amid a general suspension of ‘tabus’ or sacred regulations. The missionary William Ellis reported in 1832 from the island of Maui that it was the custom that ‘as soon as the chief had expired … the people ran to and fro without their clothes, appearing and acting more like demons than human beings; every vice was practised, and almost every species of crime perpetrated.’

The monotheistic traditions, however, placed certain obstacles in the way of explicitly treating the king himself as divine. ‘My kingdom,’ Christ pointed out to Pontius Pilate, ‘is not of this world.’ Rather than as divine beings, Christian kings ruled by divine right. Nevertheless, the urge to push monarchy in the direction of divinity still found expression, as in the rite of consecration which involved anointment by holy water. The kings of England and France supposedly possessed the power to cure scrofula, a skin disease, through their ‘royal touch’. Much of the time, it was popular appetite, more than monarchical desire, that lay behind this practice. On assuming the throne of England and Ireland, James I was unwilling to perform the cure. ‘The age of miracles is past, and God alone can work them,’ he explained. But James then bowed to popular will, becoming an enthusiastic thaumaturge and laying his hands on thousands of scrofulitic sores every year.

When it came to sacralising the king, Islam showed more flexibility than Christianity. The 16th-century Akbar was the greatest of the Mughal kings, known for his feats of empire-building, centralisation and rationalised government. But he was no less determined to emphasise the sacredness of his being. Capitalising on the fact that his reign coincided with the marking of 1,000 years since Muhammad’s death, Akbar made himself the mujaddid or ‘renewer’ of Islam as it entered its second millennium. Drawing on Sufi discipleship and ancient Persian themes, Akbar also developed a new ‘divine religion’ in which his elite vassals venerated him as a Sun-like being. His disciples saluted each other with ‘Allahu Akbar’: ‘God is great’ to be sure, but also ‘Akbar is God.’ No surprise then that he was also credited with the ability to work miracles and heal the sick.

Where are the sacred kings today? The rise of the West in the 19th century, and its continuing political and economic domination in the 20th, constituted a powerful force in favour of more secular political rulers. The way of the West seemed to be the route to modern prosperity.

Following the mid 20th-century retreat of Western colonialism, the newly independent post-colonial societies did not turn back to systems of sacred kingship. As late as 1857, the symbolic resonance of the Mughal emperor in Delhi had allowed it to become the focal point of the great rebellion of that year against British rule. By 1947, the idea was almost unthinkable.

The world had changed too much. Decolonisation saw the newly independent societies turn to secular ideologies of nationalism, socialism and communism.

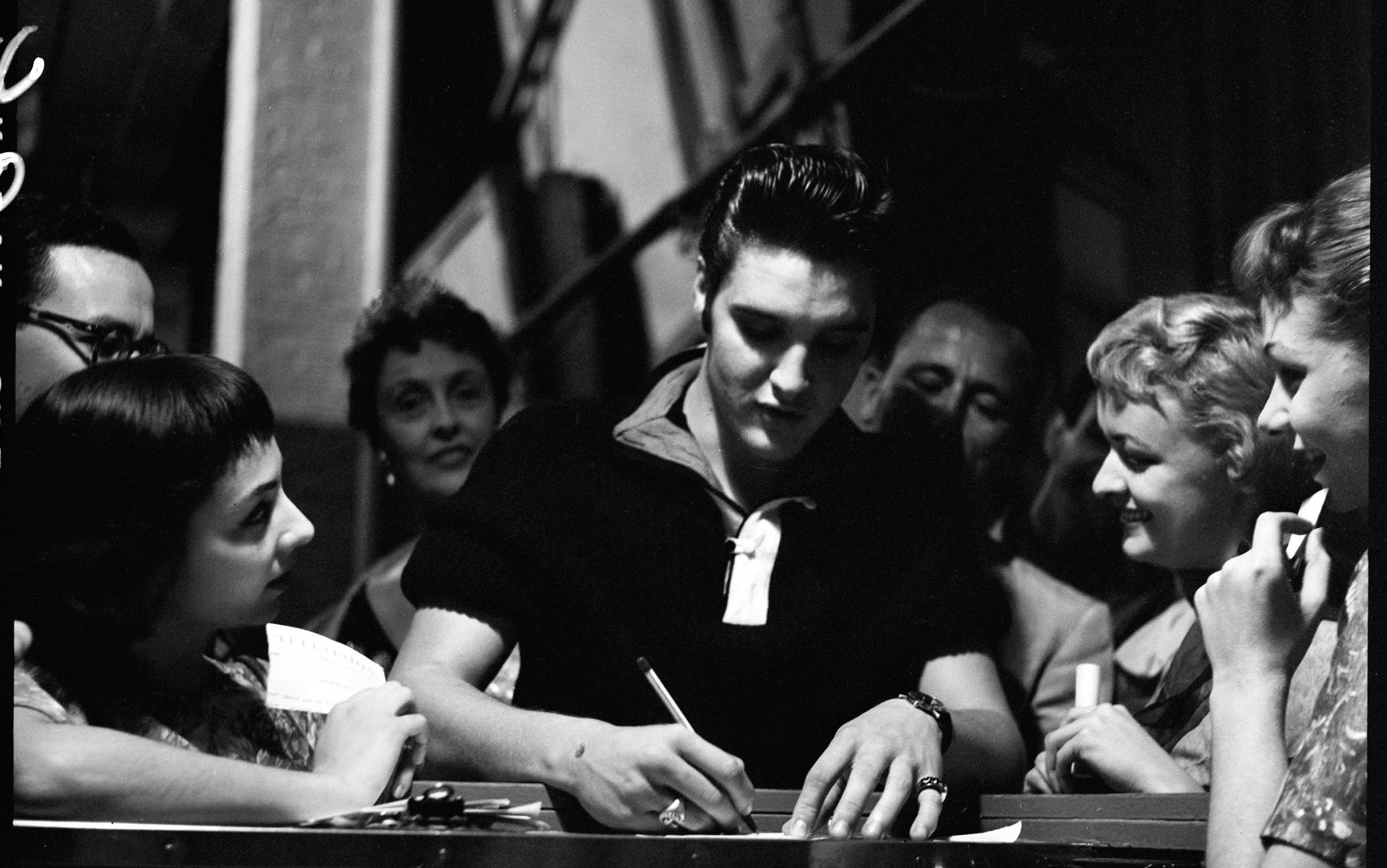

They tended to embrace the forms, if not always the substance, of democracy. Even dictators insisted that they were doing the people’s will or safeguarding the people’s destiny. Even as they took on the charisma and emotional focus that had once been the preserve of the sacred kings, they engaged in a kind of theatre of recognising the sovereignty of the people.

China’s system of sacred kingship lasted for more than two millennia. As late as 1899, the emperor of China could still confess that his sinfulness must be the cause of a drought. But after many decades of humiliating interference by Western powers, the 1911 republican revolution consigned sacred kingship to the dustbin of Chinese history. A new republican movement was born, followed by communism.

All of this is what makes Thailand, and to a lesser extent the Japanese Chrysanthemum Throne, so unusual. Although Western models of modernisation influenced both countries, Thailand and Japan avoided direct rule by European colonial powers. This helps to explain why they have been able, into the present day, to retain their sacred monarchies as symbols of national unity.

Japan’s rites of enthronement are widely understood as an act of climatic communion with the kami (gods)

In Thailand, King Bhumibol even revived an ancient ‘Royal Ploughing Ceremony’ for the start of the rainy season. A ‘ploughing lord’ – a substitute for the king himself – is appointed who has sacred bulls plough the earth accompanied by chanting brahmins. Various signs, such as what the bulls decide to eat, prophesise the bounty or poverty of the harvest. Crowds rush to gather the auspicious seeds that have fallen to the ground.

In an annual ceremony in the imperial palace, Emperor Akihito of Japan also plants rice, an echo of his ancient role in providing fertile fields for his subjects. Like Thailand, Japan escaped colonisation. In the Meiji Restoration from 1868, Japan undertook an extraordinary project of self-modernisation, swiftly adopting many elements of Western society and politics. But the emperorship was retained and indeed refashioned as a bulwark of Japanese continuity and identity. In substance, Japan is not an exception to the profoundly anachronistic status of sacred kingship in the modern world. The emperor (or tenno, ‘heavenly sovereign’) has very little real political power. But in form, the sacred rites of the Chrysanthemum Throne survive intact; indeed, it represents the oldest surviving hereditary monarchy in the world.

The rites of enthronement contain elements that go back more than 1,000 years. The present incumbent, Akihito, truly became emperor on the night of 22 November 1990 during the third and final stage of the rites of enthronement, the privately enacted daijosai. He purified himself with hot water, enveloped himself in a ‘heavenly robe of feathers’ and proceeded to two pavilions. In each of these, he offered rice and other foods to his ancestor, the Sun goddess Amaterasu, before eating them himself. Come dawn, he was reborn as the emperor. The exact meaning of this ceremony is much debated. One popular theory sees it as a rite of sexual congress with his divine ancestor. The rites of enthronement are widely understood as an act of climatic communion with the kami (gods). Through these rites, the blessing of the gods are made into the fertility of earth, the bounty of the rice fields.

In 1990, the Imperial Household was moved to deny that the rite had a mystical quality, concerned, no doubt, to observe the secular principles of the constitution, which separates religion and politics, and in line with Emperor Hirohito’s renunciation of the claim to be a living god following defeat in the Second World War. Despite the denial, the symbolism of the daijosai still evokes an idea that shaped the nature of government for most human societies throughout most of history.

The lingering presence of such ideas is striking. But they no longer rule the world. Religion obviously plays a powerful political role today, but this can blind us to recognising how profoundly that role has been transformed. Successful political leaders must claim their legitimacy through the language of demotic will, national prowess and material progress, not from their innate capacities as rainmakers, embodied gods or millennial beings. This is a relatively recent development in human history. Our ideas about what political authority is for, where it comes from, and how it operates have been profoundly secularised.