Consciousness was for a long time the charged third rail of biology: touch it and … well, maybe you didn’t die, but you were unlikely to get a grant, or tenure. Of course, it helped if you were a Nobel laureate, such as Francis Crick, lauded for his work on DNA, or Gerald Edelman, for his work on antibodies. Yet even their attempts to pin down the electrical-chemical-anatomical (or whatever) substrate of consciousness seemed, until recently, likely to go the way of Albert Einstein’s doomed search for a unified theory of everything. However, the situation has changed dramatically in recent years. Inquiry into the neurobiology of consciousness has become one of the hottest, best-funded, and most media-friendly of research enterprises, along with genomics, stem cells and a few other newly favoured sub-disciplines.

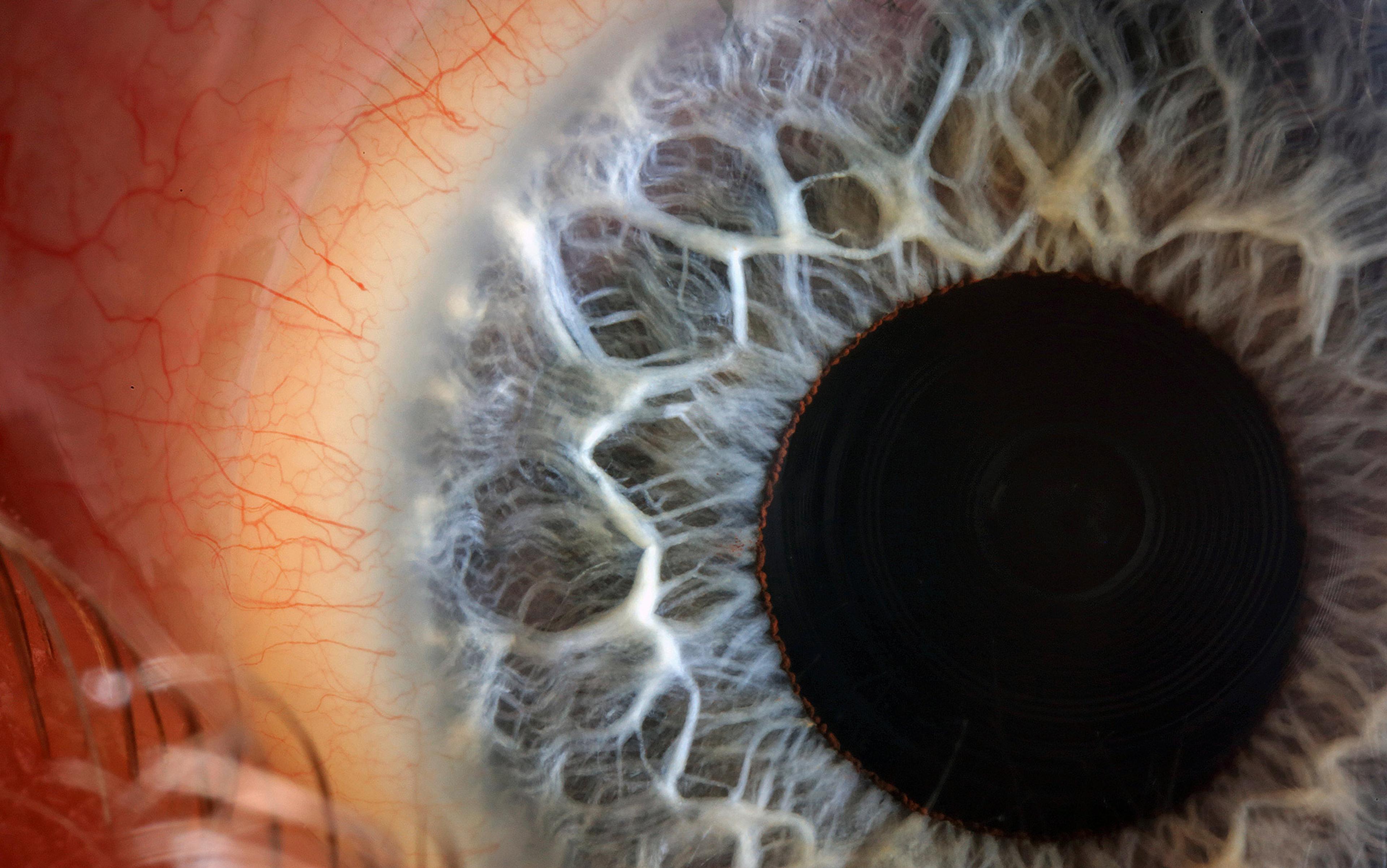

For centuries, it was perfectly acceptable for philosophers to ponder consciousness because, after all, no one actually expected them to come up with anything real. Thus, René Descartes’s renowned statement ‘Cogito ergo sum’ (I think therefore I am) becomes, in the words of the early 20th-century American satirist Ambrose Bierce, Cogito cogito ergo cogito sum — I think that I think, therefore I think that I am (which was, according to Bierce, about as close to truth as philosophy was likely to get). Now we have micro-electrodes recording from individual neurons, computer modelling of neural nets, functional MRIs, and an array of even newer 21st-century techniques, all hot on the trail of how consciousness emerges from ‘mere’ matter. Cartesian dualism is on the run, as well it should be.

Admittedly, there are some exceptions to this scientific turn of events, proving that imbecility runs deep in humans, especially in the curious world of the consciousness-credulous. Take the persistence of beliefs that rocks or whole planets are conscious, or the remarkable popularity a decade ago of the charlatan film What the Bleep Do We Know? (2004) with its faux-scientific assertion that consciousness is an active force by which we can affect the world.

I know I am conscious, and I also know that my dogs are aware. But are they conscious?

This film also showcased the Japanese entrepreneur Masaru Emoto’s ludicrous — and persistently unreplicated — claim that water forms different kinds of crystals as a result of being exposed to varying ‘dimensions of consciousness’. Allegedly, written messages such as ‘You jerk’ produced only ugly crystals or none at all, while ‘I love you’ brought forth beautiful, heart-warming symmetrical delights. And don’t forget the English expert on telepathy in pets, Rupert Sheldrake, babbling about ‘morphogenetic fields’ which posits that the universe has its own inherent memory. Or the Australian TV producer Rhonda Byrne’s continuing barrage of nonsensical, yet best-selling Secret books, whose ‘secret’ is that your conscious desire for something can, by itself, make things happen in the real world. With such friends, the serious study of consciousness hardly needs enemies.

Perhaps a bit of definitional clarity would help. Or at least a gesture in that direction, a modification, if you like, of the US Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart’s oft-repeated observation about pornography: we might not be able to define consciousness, but we know it when we experience it. I propose that consciousness can be defined as a particular state of awareness, characterised by a curious recursiveness in which individuals are not only aware, but aware that they are aware. By this conception, many animals are aware but not strictly conscious. My two German shepherd dogs, for example, are exquisitely aware of and responsive to just about everything around them — more so, in many cases, than me. I know, however, that I am conscious because I am aware of my own internal mental state, sometimes even paradoxically aware of that about which I am unaware.

I know I am conscious, and I also know that my dogs are aware. But are they conscious? Frankly (and speaking now as an animal-loving human observer, rather than as a scientist), I have little doubt that they are conscious, and that my cats are, too, and my horse as well … although as a biologist, I can’t prove it. A more satisfying stance, therefore — empathically, as well as ethically — is to give in to common sense and stipulate that different animal species possess differing degrees of consciousness. This might be more intellectually satisfying as well, since postulating a continuum of consciousness is consistent with the fundamental evolutionary insight of cross-species research: organic continuity. Most likely, consciousness ranges across a spectrum rather than being a special state that only humans experience.

My intent is neither to bury nor to praise the neurobiology of consciousness — although I certainly prefer it to the grotesquely unscientific drivel that has emerged as its alternative — but to point instead to another side of bona fide ‘consciousness research’ that has received all too little attention. I refer to the question of why consciousness exists at all. Evolutionary biologists find it useful to distinguish two basic kinds of questions: proximate and ultimate, which essentially equate to ‘how’ versus ‘why’.

To understand this distinction, think of the phenomenon of bird migration: what ‘causes’ it? In answering this question, we could examine the possible role of hormones, or of changes in day length, food availability, and so forth. Or we might look into the particular brain regions that are involved, the potential impact of social learning versus instinct, etc. All are valid approaches, but they share a common limitation: each is concerned only with the proximate mechanisms that initiate migration, that is, with matters of ‘how’ migration happens.

By contrast, inquiry into ultimate or evolutionary causation concerns itself with ‘why’. Why migrate at all, instead of staying at home? Given the costs of migration, what are the benefits that have presumably favoured the evolution of this phenomenon — regardless of its attendant mechanisms — in the first place? Biological research is at its best when grappling with both proximate and ultimate causation.

Isn’t it enough to feel, without also feeling good — or bad — about the fact that we are feeling?

So, let’s grant a ‘how’ to consciousness. Somehow or other, energy and matter come together and produce it, via electrochemical events across neuronal membranes. The process itself is still a puzzle, one that is being vigorously tackled today. Nonetheless, even if the immediate causation of consciousness was somehow solved, it would still leave unresolved the question of ‘why’, the ultimate cause (or causes) of consciousness, the reason it evolved in the first place. After all, it is quite possible to imagine a world inhabited by highly competent (even highly intelligent) zombies, who go about their days responding appropriately to stimuli — basking, perhaps, in the warm sun, obtaining suitable nutrients at opportune times, even repairing themselves — but lacking consciousness. Computers are highly intelligent: they can win at chess and perform very difficult calculations, but they don’t show any signs of possessing an independent and potentially rebellious self-awareness, as HAL does in the science fiction film 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968).

Nearly everyone — even the most enthusiastic zombie aficionado (of whom there are a remarkable number these days) — agrees that most people, most of their waking lives, are conscious. In fact, consciousness could well be a sine qua non, necessary but not sufficient for humanness, all of which leads inevitably to the question: why has consciousness evolved?

Let me put it another way. Why should we (or any conscious species) be able to think about our thinking, instead of just plain thinking, period? Why need we know that we know, instead of just knowing? Isn’t it enough to feel, without also feeling good — or bad — about the fact that we are feeling? After all, there are downsides to consciousness. As the American cultural anthropologist Ernest Becker put it.

The idea [of consciousness] is ludicrous, if it is not monstrous. It means to know that one is food for worms. This is the terror: to have emerged from nothing, to have a name, consciousness of self, deep inner feelings, and excruciating inner yearning for life and self-expression — and with all this yet to die.

For Dostoyevsky’s Grand Inquisitor, consciousness and its requisite choices comprise a vast source of human pain (one that he obviated by telling people how to think and what to believe).

There are also some practical problems. As a result of excessive ‘self-consciousness’, we (unlike dogs, cats, or horses, for example) are liable to trip over ourselves, whether literally when attempting to perform some physical act best done via the ‘flow’ of unreflective automaticity, or cognitively, because of the infamous, chattering ‘monkey mind’ that is anathema to Eastern philosophies and religions, and which can require intense meditation or other disciplines to squelch. It might well be ironic that many of these wisdom traditions yearn precisely for what is essentially an animal state of full awareness, but without self-consciousness. Even on a strictly biological basis, consciousness seems hard to justify, if only because it evidently requires a large number of neurons, the elaboration and maintenance of which is bound to be, in terms of energy, expensive. What is the compensating payoff?

Bear in mind that, for consciousness to have been selected for over evolutionary time, individuals (and their consciousness-promoting genes) would have to be more successful in propagating copies of those genes in the future than owners of alternative genes that generated less consciousness, or none at all. The bottom line is that consciousness should have paid its way.

One possibility — a biological null hypothesis if you like — is that consciousness hasn’t been selected for at all. Maybe it is just a nonadaptive by-product of having brains bigger than is strictly necessary for bossing our bodies around. A single molecule of water, for example, isn’t wet. Neither are two, or, presumably, a few thousand, or even a million. But with enough of them, we get wetness — not because wetness is adaptively favoured over, say, dryness by the evolutionary process, but simply as an unavoidable physical consequence of piling up enough H2O molecules. Could consciousness be like that? Accumulate enough neurons — perhaps because they permit its possessor to integrate numerous sensory inputs and generate complex, variable behaviour — wire them up and, hey presto, they’re conscious?

Consciousness might, then, be comparable to male nipples. These structures serve no obvious adaptive function; they exist because when present in women, they clearly are beneficial to the evolutionary success of their possessors, in facilitating lactation and nursing. So, male nipples are almost certainly evolutionary byproducts, not selected for in themselves, but generated by natural selection nevertheless. (It would take a major rearrangement of the human genome, as well as re-routing embryological development, to dispense with nipples in one sex while retaining them in the other.)

Alternatively, maybe consciousness really is adaptive. This would mean that those who are conscious are more ‘fit’ (in the evolutionary sense) than those lacking this trait. More precisely, genes that contribute to consciousness must somehow have been more successful than alternative alleles in getting themselves projected into the future.

One possibility is that consciousness gave its possessors the capacity to overrule the tyranny of pleasure and pain

Brief explanatory excursion: it is a useful exercise to ask what brains are for. From an evolutionary perspective, brains evolved not simply to give us a more accurate view of the world, or merely to orchestrate our internal organs or coordinate our movements, or even our thoughts. Rather, brains exist because they maximise the reproductive success of the genes that helped create them and of the bodies in which they reside. To be adaptive, consciousness must be like that. Insofar as it has evolved via natural selection, consciousness must exist because brains that produced consciousness were evolutionarily favoured over those that did not. But why?

One possibility is that consciousness gave its possessors the capacity to overrule the tyranny of pleasure and pain. Not that pleasure and pain are inherently disadvantageous. Indeed, both have adaptive significance in themselves. Pleasure is as a proximate mechanism that encourages us to engage in activities that are fitness-enhancing, while pain should help us to refrain from those that are fitness-reducing. But what about things that are fitness-enhancing in the long run, but unavoidably painful in the short? Or vice versa? It might feel good, for example, to overeat, but it’s nonetheless detrimental. In this case, perhaps a conscious individual can say to himself: ‘I want to gnaw a bit more on this gazelle leg, but I’d better not.’ Or vice versa: ‘I don’t want the pain of pulling my infected tooth out, but if I do it, I’ll be better off.’ Once an individual starts mulling things over, essentially talking to herself about herself, she is en route to consciousness.

However, even more intriguing than its use as a facilitator of impulse control is the possibility that consciousness evolved in the context of our social lives. Human societies privilege a kind of Machiavellian intelligence whereby success in competition and co-operation depends on our evolved ability to imagine another’s situation no less than our own. That isn’t so much out of intended benevolence (although this, too, could be the case) but because such leaps of the imagination allow us to maximise our own interests in the very complex landscape of human societies.

Thus, consciousness is not only an unfolding story that we tell ourselves, moment by moment, about what we are doing, feeling and thinking. It also includes our efforts to interpret what other individuals are doing, feeling and thinking, as well as how those others are likely to perceive us in return. Call it the Burns benefit, from the last stanza of the Scottish poet’s celebrated 18th-century meditation, ‘To a Louse’:

O wad some Power the giftie gie us

To see oursels as ithers see us!

It wad frae mony a blunder free us,

An’ foolish notion…

If, as is sometimes suggested, character is what we do when we think no one is looking, maybe consciousness is precisely the inverse. Consciousness is a gift, à la Robert Burns, that allows us to anticipate how we might appear to others while we do what we do. Thus, our social intelligence could have effectively helped to free us from many a blunder and foolish notion, by enabling our consciously endowed ancestors to realise (in proportion to their consciousness) that seeming too selfish, or insufficiently altruistic, or too cowardly, too uninformed, too ambitious, too sexually voracious and so forth would ill serve their ends. The more conscious our ancestors were, according to this argument, the more able they were to modify — to their own benefit — others’ impressions of them and, hence, their evolutionary success. And if that were so, then genes ‘for’ consciousness would have enjoyed an advantage over alternative genes ‘for’ social obtuseness.

In recent decades, my psychology colleagues have been much exercised over ‘Theory of Mind’, a cognitive capacity for inferring the mental attributes of others. To have Theory of Mind means that one is capable of constructing a variety of hypotheses about what is going on inside another’s head and, therefore, having a much better shot at predicting his or her behaviour. It might be possible to make accurate inferences of this sort without consciousness, but it seems likely that the more inclusive the consciousness of individual A, the more successful she will be in constructing a valid model of the inner workings and, thus, the eventual behaviour, of individual B.

It is one thing to conclude, without reflection and on the basis of observable behaviour: ‘That fellow over there is angry and hence, dangerous.’ It is certainly something a dog is capable of doing. It seems to me that a human being has the wider range here, and the evolutionary advantages of being able to think something more, something like: ‘He seems angry, just as I was when something similar happened to me. Since I responded the way I did at the time, I bet he’ll respond similarly.’

A Theory of Mind allows the ability to forecast and predict another’s action in a far more complex, and therefore fruitful, way. In 1978, the American psychologists David Premack and Guy Woodruff wrote a much-noted paper in the journal Behavioral and Brain Sciences entitled ‘Does the chimpanzee have a Theory of Mind?’ — a question that the authors tentatively answered in the affirmative. This sparked a long-running debate, in which the tide turned for and against the idea a number of times. Thirty years later, in 2008, Josep Call and Michael Tomasello of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany suggested in an influential review in Trends in Cognitive Science that the chimpanzee situation is more nuanced. On the one hand, these apes are evidently capable of understanding the goals, intentions, perceptions and internal knowledge states of other individuals (so long as these correspond to the world as it appears to an observing chimpanzee). But, on the other hand — and unlike human beings — chimps are unable to internalise situations in which other individuals have false beliefs about the external world (ie, when person A understands what person B mistakenly think to be the case, even though person A knows it to be wrong).

It’s not so much the meek as the conscious who have inherited the Earth

It therefore appears at present that human beings, although probably not unique in possessing Theory of Mind, are nonetheless unusual in the degree of its sophistication, specifically in the extent to which they can accurately model the minds of others. It seems highly likely that those who possessed an accurate Theory of Mind enjoyed an advantage when it came to modelling the intentions of others, an advantage that continues to this day, and was an active ingredient in the evolution of human consciousness. And it is at least possible that the more conscious you are, the more accurate is your Theory of Mind, since cognitive modellers should be more effective if they know, cognitively and self-consciously, not only what they are modelling, but that they are doing so.

Simon Baron-Cohen, director of the Autism Research Centre at Cambridge University, has championed the hypothesis that people suffering from autism suffer from various degrees of ‘mind blindness’ — that is, deficiencies in their ability to model Theory of Mind. Hence, according to Baron-Cohen, their emotional lives are strangely depauperate or lacking, especially when it comes to their ability to understand — at a deep emotional level — the thoughts and feelings of others.

There is, of course, no evidence that people experiencing autism (whether in its milder form as Asperger syndrome, or in its severe and socially disabling manifestation) are in any meaningful sense ‘less conscious’ than anyone else, but the struggles that they encounter in negotiating the social landscape do give us some idea of the advantages of a theory of mind, as part of the package of human consciousness. (Another possibility — which does not exclude likely deficiencies in generating Theory of Mind — is that autism correlates with inadequate or insufficient ‘mirror neurons’, which is another story, to be discussed, perhaps, at another time.)

At the proximate level, regarding the ‘how’ or manner of its manifestation, we are confident that consciousness derives from material events occurring among neurons. On the other hand, at the ultimate level, the ‘why’ of consciousness is unquestionably a matter of its evolutionary significance, occurring at the level of ecology and natural selection. Nonetheless, many are convinced that consciousness can have come to us only as a gift from God, an endowment enabling His chosen species to glorify the divine and do so with full, aware — conscious — commitment to the saving of their souls.

Similarly, there are those who maintain a mystical conception of the power of ‘cosmic consciousness’ to move mountains, or at least, as the countercultural Yippies attempted in 1967, to levitate the Pentagon via concentrated psychic energy (an effort that, as I recall, never got off the ground). Others have an unshakeable confidence that we are surrounded by disembodied ‘morphogenetic fields’ or other ineffable manifestations of some cerebral happening of which the merely material is only a pale semblance.

‘But we are not only here concerned with hopes or fears,’ wrote Charles Darwin, at the end of The Descent of Man (1871), ‘only with the truth as far as our reason permits us to discover it.’ He went on:

[W]e must, however, acknowledge, as it seems to me, that man with all his noble qualities, with sympathy which feels for the most debased, with benevolence which extends not only to other men but to the humblest living creature, with his godlike intellect which has penetrated into the movements and constitution of the solar system — with all these exalted powers — Man still bears in his bodily frame the indelible stamp of his lowly origin.

To which I would add that we also bear this stamp — of biology — in our consciousness, not just when it comes to the ‘how’ but also the ‘why’. My own, fully conscious guess at this time is that it’s not so much the meek as the conscious who have inherited the Earth. Ironically, those self-consciously conscious creatures who have done so are nonetheless a long way from understanding either the ‘how’ or the ‘why’ of their own remarkable mental capacities. Until they do so, their claim to God-like superiority over their less-conscious cousins will continue to bear the ‘indelible stamp’ of how the imaginative reach of Homo sapiens continues to exceed its scientific grasp.

This essay is adapted from David Barash’s recent book Homo Mysterious: Evolutionary Puzzles of Human Nature (2012)