In the cleanest college library I’ve ever seen, women of various ages and ethnicities were seated around a long wooden table. A few were chatting, but most were nervously shuffling notebooks and pens or staring at the floor. The men – there were five, ranging in age from early 20s to mid-50s – showed up just before class began. I tried to divine, one by one, what horrible tragedy had brought them all there.

This was the Tuesday night forgiveness course at Stanford University. I was there strictly to observe. Formalised forgiveness training – complete with a reading list, lectures, practice sessions and homework – was for people who had survived genocide, not for me with my garden-variety baggage (even if I had read everything I could about forgiveness training, developing a not-unhealthy obsession with the topic). Professor Frederic Luskin told me I could sit in on his class, but would have to participate so it wouldn’t seem weird. No problem. I prepared an almost-true story about a fight with my mother.

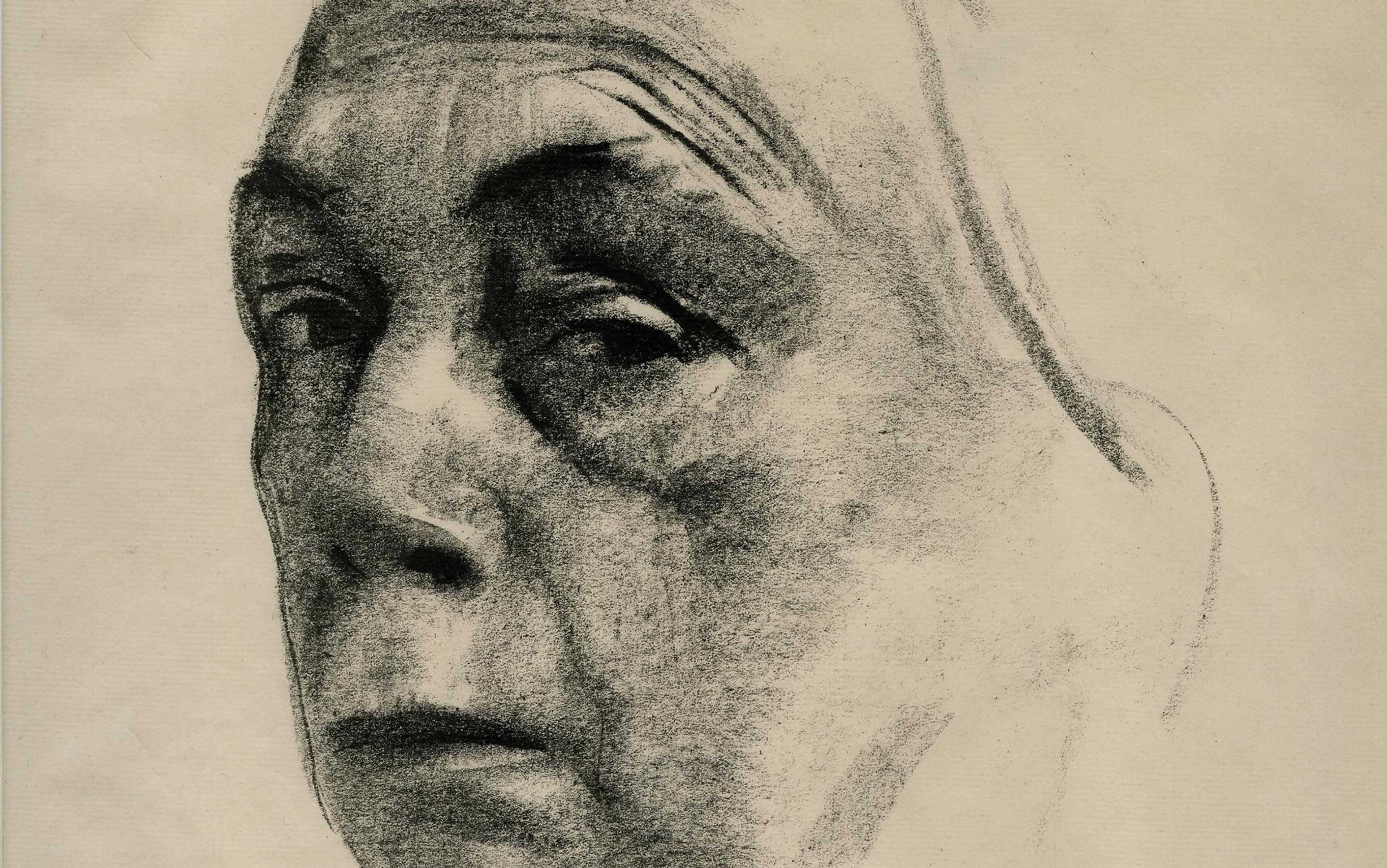

Then, his large eyes flashing and greying hair standing on end, Luskin held his hands out in front of him like a zombie, palms down and spaced about a foot apart. ‘Most of our disappointment in life stems from wanting this,’ he jabbed at the air with his left hand, the higher of the two, for emphasis, ‘and getting this,’ he said, jiggling the lowered right hand. Then he stared at all of us, intently. ‘OK? And forgiveness is about what you decide to do with this space in the middle. Are you going to adjust what you expect and let the rest go, or are you going to live in this space? Because I’ll tell you what, living in there is miserable.’

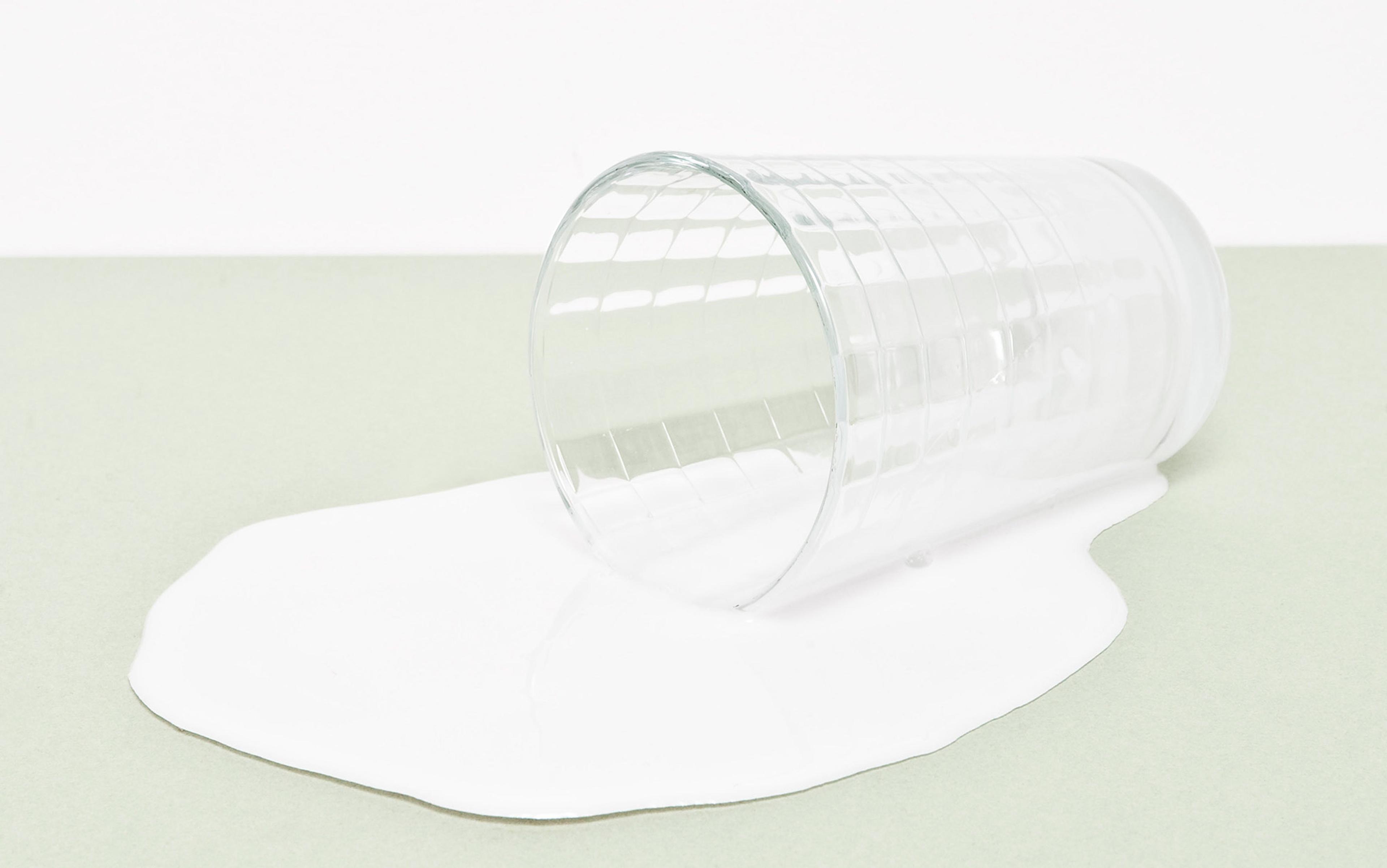

Shit. Now all I could think about was living in that terrible, empty space between his two giant hands. How I’d been stuck there for years, waiting for things to change and then being angry and disappointed when nothing happened.

When we got paired off to share our stories, my fake mom story was running through my head on rapid repeat, but my mouth rebelled, blurting out to the nice man on my left: ‘My best friend died and now I hate everyone for not being her and I really need to let it go. And actually this is really weird because Leah died here. Not right here in this library, but over there at the university hospital. This is the first time I’ve been back since.’

It was a moment I’d read about – this sudden shift when the need to forgive outweighs the drive for revenge. I felt weightless, nauseous, sad, the prospect of letting go of all those years of anger finally opening up a space for grief. It is this rare freedom for the soul that has made forgiveness a cornerstone of all major world religions for hundreds of years as well as an increasingly popular subject in modern psychology – both the traditional and pop varieties. But while its benefits have been proved, forgiveness remains a thorny subject, bound up in ideas about everything from doctrinal religion to justice.

My researches began when I stumbled across a story about Robert Enright, a psychologist at the University of Wisconsin. Enright was raised Catholic, but abandoned religion for academia early in his career. ‘I became a professor and thought I knew who God was – it was me,’ he said.

By the time he returned to his faith, Enright had established himself as ‘the father of forgiveness’, creating a therapeutic protocol for how to practise it that was officially sanctioned by the American Psychology Association and the United Nations. He thought the Catholic Church could be doing more to emphasise its deep history in the subject, and spreading the gospel of forgiveness to the masses, and said so in a speech at the Vatican.

I knew exactly how to ask God for forgiveness, but I had no idea how to forgive, or ask forgiveness from the people in my life

As a lapsed Catholic myself, Enright’s story resonated with me. Forced to attend church and Catholic school in my youth, I’d rebelled in my teens and twenties, not because I didn’t believe in God but because I didn’t like the self-righteous way in which most of the religious people I knew behaved. I didn’t really miss religion, apart from those moments at the end of Mass where Holy Communion absolved me of my sins and I’d be given a few moments of silence to pray in gratitude. I’d looked forward to those moments – and the peace they brought me – every week. Few other experiences delivered a similar relief from daily worries, and when I read about Enright and his work I wondered if forgiveness might be the thing.

Each of the Abrahamic faiths – Islam, Judaism, Christianity – include teachings on forgiveness, both the sort that God doles out and the sort that human beings can (and should) bestow on each other. The Torah, the Bible, and the Qur’an are all filled with dictates about forgiveness, and rules about what God can and cannot, or will not, forgive. The non-Abrahamic faiths, meanwhile, have a wellness-focused approach to forgiveness that’s not so different from modern, secular treatments of the subject in the context of the positive psychology movement. Buddhism, for example, teaches that people who hold on to the wrongs done to them create an identity around that pain, and it is that identity that continues to be reborn.

But what about the nuts and bolts of forgiveness, about which all the Catholic rituals around penance and confession had taught me nothing? I knew exactly how to ask God for forgiveness, but I had no idea how to forgive, or ask forgiveness from the people in my life. This turns out to be an important distinction: University of Michigan researchers have found that forgiveness between people tends to have more reliably positive physical benefits than any perceived forgiveness from God.

Forgiveness is a relatively new academic research area, studied in earnest only since Enright began publishing on the subject in the 1980s. The first batch of studies were medical in focus. Forgiveness was widely correlated with a range of physical benefits, including better sleep, lower blood pressure, lower risk of heart disease, even increased life expectancy; really, every benefit you’d expect from reduced stress. The late Kathleen Lawler, while working as a researcher in the psychology department at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville, studied the effects of both hostility and forgiveness on the body’s systems fairly extensively. ‘Forgiveness is aptly described as “a change of heart”,’ she wrote, in summarising a series of studies focused on the impact of forgiveness on heart health. Meanwhile, Duke University researchers found a strong correlation between improved immune system function and forgiveness in HIV-positive patients, and between forgiveness and improved mortality rates across the general population.

More recently, the subject has surged in popularity as everyone from the United Nations to the victims of mass shootings espouses the virtues of forgiveness for everything from mental health to managing war zones. Even Oprah Winfrey has gotten in on the forgiveness game: her favourite life coach, Iyanla Vanzant, frequently spotlighted the subject in her Oprah Winfrey Network show Iyanla: Fix My Life, and launched an e-learning class entitled ‘How to Forgive Everyone for Everything’.

In her book, Forgiveness: 21 Days to Forgive Everyone for Everything, Vanzant lays out a 21-day programme to set readers on the path to forgiveness. Perhaps unsurprisingly (Winfrey is the queen of self-improvement, after all), the book is focused largely on self-forgiveness. Vanzant is also a proponent of Progressive Energy Field Tapping (Pro EFT) – tapping specific energy points just under the surface of the skin, ‘releasing emotions trapped in our energy system’, according to the official Pro EFT website. It’s a bit New Age-y for my taste, but hey, it’s a process and a lot of people are saying it works.

It’s not just Oprah who’s promoting the self-improvement side of forgiveness. The rise of popular interest in forgiveness has coincided with a second wave of academic studies, focused on self-forgiveness. After investigating the relationship between forgiveness and health, Jon R Webb at East Tennessee State University found that ‘it may be that forgiveness of self is relatively more important to health-related outcomes’ than other forms of forgiveness. Sara Pelucchi, at the Catholic University in Milan, claims that it is beneficial to romantic relationships, and Thomas Carpenter at Baylor University found that we have an easier time forgiving ourselves if those we have hurt forgive us first.

Enright has also examined self-forgiveness, although he’s more measured about it than Vanzant. ‘The issue of self-forgiveness is much more complicated than forgiveness in general and here’s why: when you offend yourself, you are both the victim and the perpetrator,’ he told me. ‘The problem is compounded by the fact that we rarely offend ourselves in isolation from offending others.’

Enright recommends that people struggling with self-forgiveness learn to forgive others first, before offering that same compassion to themselves. ‘Otherwise it can be tricky: If you’re a compulsive gambler and keep squandering the family’s money, for example, you could forgive yourself and keep doing it, but true self-forgiveness requires stopping the behaviour that led to the offence in first place.’

It’s the ‘learn to forgive’ part that’s key to making forgiveness stick. According to Luskin, religion might help to motivate or oblige people to forgive, but it’s the secular realm that is bringing the idea of forgiveness to the masses. It’s also teaching us precisely how to do it.

Her father had killed her cat and buried it in the carrot patch, then laughed gleefully when the horrified child uncovered her dead pet

While researchers have spent the past 20 years proving the physical and mental benefits of forgiveness, it’s the step-by-step forgiveness guides they’ve developed that might turn out to be academia’s most important contribution to the subject. Like Vanzant’s pop-psych version, the protocols that Enright and Luskin have developed offer specific steps towards forgiveness rooted in decades of research and clinical experience. While the various approaches differ, all include practical guidance and the basics are consistent: feel the feelings you need to feel, express them, then leave them in the past where they can no longer have power over you.

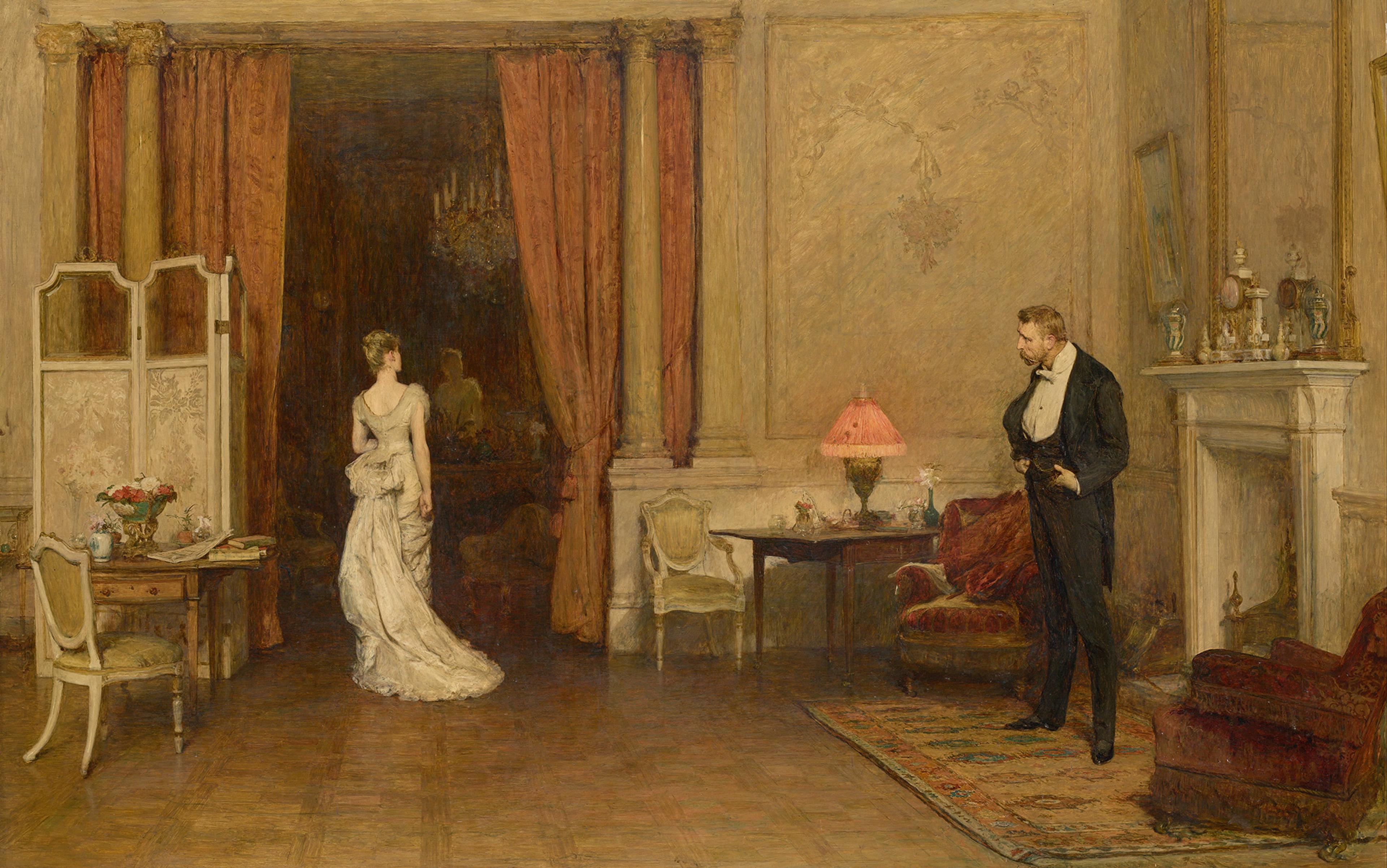

When I first met my friend Leah, it was all off-colour jokes and dares. Then she invited me to her ex-boyfriend’s funeral and things got real. I met her mother, who was sweet and funny and cooked us dinner in an apron, but also smoked around Leah even though it was likely to trigger an asthma attack. Her father, a retired physician, and the sort of stiff grown-up that people like me (and Leah) loved to get a rise out of, patted Leah’s shoulder and tousled her hair as we got into the car to leave.

Later Leah said that was the most affection he had ever shown her in public. Then she told me how, when she was about five, her father had killed her cat because it was annoying him, and had buried it in the carrot patch. Telling her to go find it there, he had then laughed gleefully when the horrified child uncovered her dead pet. We traded unpleasant stories the whole ride home, and after that our friendship was sealed.

Shortly after that outing, I barged into her apartment and found her on her living-room floor wheezing in and out of a massive steroid inhaler. She explained that she had cystic fibrosis and that her brother had died from it, but that she, the beneficiary of various trial drugs, would most likely be OK.

A couple years later, after we graduated from college, I got Leah a job at the magazine where I worked. When I had to fire her because she showed up late every day and spent hours hanging out under my desk, sipping lattes, I didn’t make up excuses or lie. I just called her at the end of the day and, before she could even say ‘Hello?’ I yelled: ‘You’re fired!’

She erupted in laughter.

‘No, but seriously, you’re fired. I mean, come on, I don’t think you’ve made it to the office on time once. Plus you spend most of that time under my desk. AND you really blew that call the other day.’

Our boss had asked her to make some advertising sales calls. Leah’s technique had been to play it cool and say: ‘I know the last thing you want to do is advertise, especially in this lousy magazine.’ She thought they’d find it refreshing and humorous, but our boss, overhearing her, did not appreciate her creativity.

‘Ach. Yeah, OK, I get it. I’m sorry – did I get you into trouble?’

‘No, but I think having me fire you is some sort of test.’

‘Well, tell that egg-shaped douche you passed.’

In my first conversation with Enright, he explained that he’d started researching forgiveness in 1985, ‘when no one in the social sciences would even touch the topic. It was either totally off their radar or just too scary because it is really rooted in the monotheistic traditions. I thought that was folly. Forgiveness might be important to the human condition and scientists have the obligation to go where the ideas lead, no matter what.’

That conversation led to other scholars who had waded into forgiveness research, Luskin among them. Like Enright, Luskin had worked with civil war survivors (in Sierra Leone), various factions within Northern Ireland, and death row inmates in the United States. When I found him, Luskin had been running forgiveness classes at Stanford for about a decade, and had moved away from what he called the ‘big, dramatic’ forms of forgiveness, to which youth and media attention had drawn him early in his career.

We live on a planet where harm happens all the time; to think that you should escape that is a mammoth overstatement of your own importance

‘Even the stuff that forgiveness was supposed to be good for – stuff like murders … it’s so rare,’ he told me. ‘More important is can you forgive your brother-in-law for being annoying? Can you forgive traffic? Those things happen every day. Big things? They happen once in a lifetime, maybe twice. It’s a waste of forgiveness. That’s my perspective. But forgiveness is really important for smoothing over the normal, interpersonal things that rub everyone the wrong way.’

Part of what makes the word – and practice – tough for people, in Luskin’s view, is that it requires a degree of selflessness. ‘For me to say, “Even though you were a shithead, it’s not my problem; it’s your problem, and I’m not going to stay mad at you, because that’s you, not me,” that’s a huge renunciation of self,’ he said. ‘And I don’t know whether it’s our [Western] culture or a human thing, but it’s hard.’

Plus it requires acknowledgement of our fundamental human vulnerability, without getting angry or bitter about it. ‘A lot of times people start with this idea that “I shouldn’t have been harmed”,’ Luskin said. ‘Why not? We live on a planet where harm happens all the time, where children are murdered and horrible things happen; to think that you should escape that is a mammoth overstatement of your own importance and a lack of sensitivity to everyone else on the planet.’

But even for those who might find themselves nodding along with Luskin’s sentiments, walking the walk is another story. What all of the researchers and pop-psych proponents of forgiveness agree on is that it takes practice and that it is hard work. Vanzant compares it to pulling out a tooth without Novocaine. Luskin described it as re-training the brain. ‘You can get upset about anything – you can also get un-upset about anything, it’s just a matter of learning how,’ he said.

In the eight years since Leah died, I’ve married, had a child and made new friends, yet I still miss her desperately. If I had a bad experience at work, Leah thought I should quit. Screw them. If I argued with a boyfriend, he was an asshole. Period. Even when everyone, including me, knew I was the asshole. It was the kind of backup she craved, too, which is why it’s been so hard to shake the feeling that ultimately I failed her.

Toward the end of her life, Leah’s doctors said the only way she’d be able to continue living was on a ventilator. Knowing she wouldn’t want to live that way, her parents decided to take her off life support. I agreed with their choice, difficult as it would be to lose her. When I went to be with her on that last night, she was alone. Her parents couldn’t bear to see Leah suffer the same slow, painful death they’d watched their son endure. I couldn’t imagine doing otherwise.

When the nurse took Leah off the machines, she panicked, opened her eyes wide, clenched my hand and mouthed, ‘Help me.’ Several hours later, when the nurse came to check on her, she reported with surprise that Leah’s blood oxygenation levels were normal. When I asked what that meant, she said, ‘Well, it means she didn’t really need to be on that ventilator.’ At that point, I asked if we shouldn’t reconsider things, but the nurse was quick to squash that idea. ‘I’ve probably just had her on too much oxygen,’ she said. ‘I’ll turn it down.’

It is the biggest regret of my life that I didn’t make a huge fuss in that moment, and demand to see the doctor. That I did not call Leah’s parents and beg them to reconsider. That I did not wait until the nurse left the room, then jack the oxygen back up. That I did precisely nothing but hold my friend’s hand while she died.

In the weeks following Luskin’s forgiveness seminar, it all clicked. I’d been waiting for a magical moment in which I would forgive myself for failing Leah – and the rest of the world for being around when she wasn’t. That moment never came and in the meantime, I had justified a lot of my own bad behaviour.

After reading everything from religious scripture to academic studies, I finally realised that’s not at all how forgiveness works, and that’s what makes it so damn hard. Time does not heal all wounds. This too shall not pass. Letting go of hurt and anger is a grind, and forgiveness only works if you practise it regularly, and are prepared to fail often without giving up. But the pay-off is so huge it just might be worth it.