My paternal grandfather Anis was born an Ottoman subject in 1885 but died an Arab citizen. He passed away in 1977 at the age of 92, two years into Lebanon’s civil war. Raised in Tripoli when all the Arab East lay under Ottoman sovereignty, and educated in American mission schools that dotted the Empire in its last century, Anis Khoury Makdisi became a distinguished professor of Arabic at the American University of Beirut. Best known for his works on Arabic literature, he was known as ‘Ustadh Anis’ – a teacher of generations of students of Arabic in the Middle East’s most renowned modern university. He was also a proud member of the Arabic language academies of Cairo and of Damascus, institutions that embodied a modern age of coexistence that shaped the Arab Muslims, Christians and Jews of my grandfather’s generation.

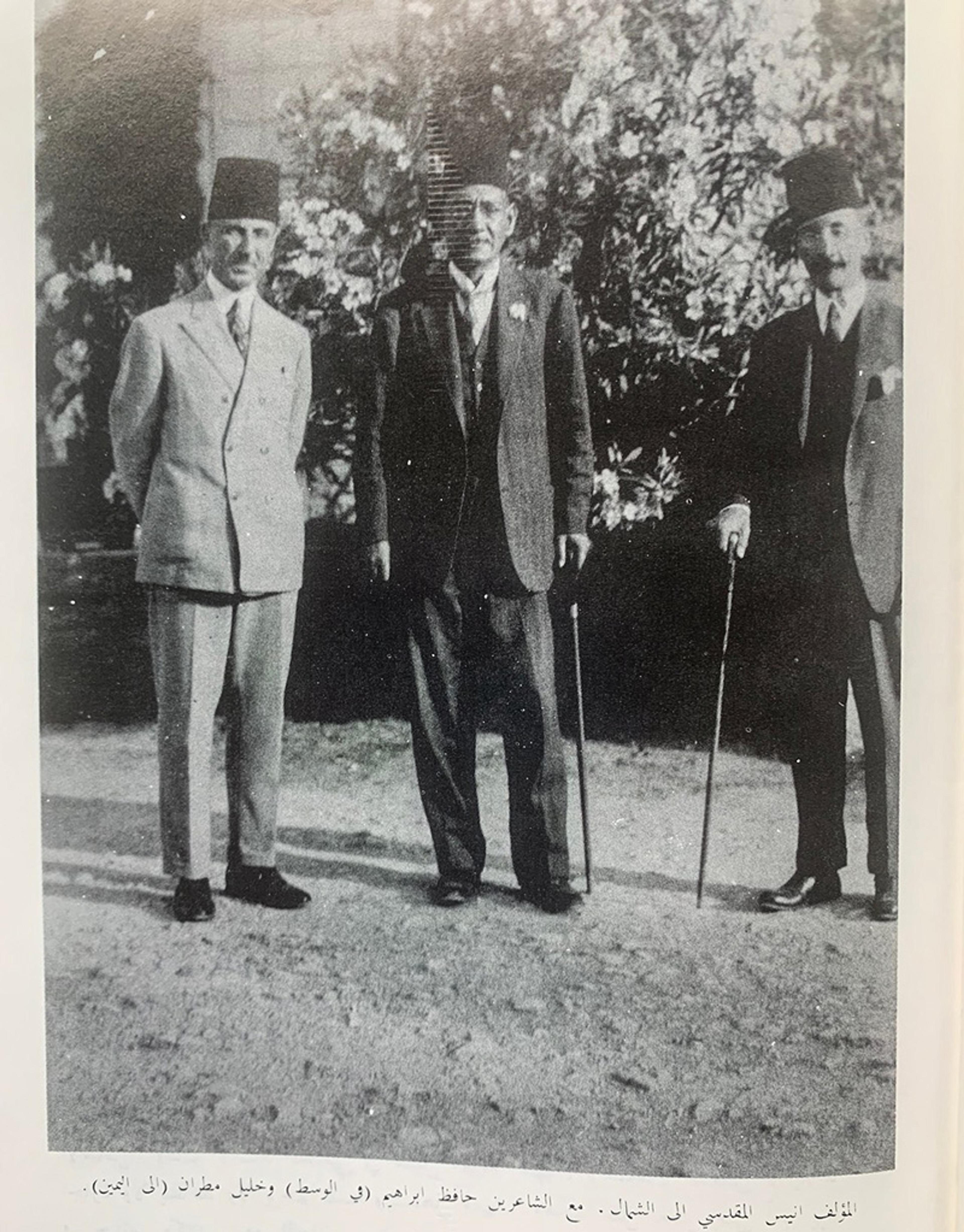

The author’s grandfather Anis Khoury Makdisi (l) pictured alongside Hafez Ibrahim (c) and Khalil Mutran (r) circa 1920. From his memoir In the Company of Time, eds. Y.Ibish & Y.K. Khoury, Beirut and courtesy the author.

His generation shared more than a language and a civilisation. It believed that it could revive and lead itself into a modern Arab future. For Anis, as for so many of his compatriots, religious difference posed a sectarian conundrum, but they refused to see it as an insurmountable barrier to national solidarity. Sectarianism was one problem among many others, including ignorance, corruption and tyrannical government, all of which stood for his generation of Arab intellectuals at the turn of the century as real, but not necessarily fatal, dangers.

By the time I was born in 1968, my grandfather was an emeritus professor and a pillar of Ras Beirut’s small and highly educated Protestant community. But by then, as well, the optimism of the first half of the 20th century had receded dramatically. European empires had long since cynically partitioned the Ottoman Empire and created several new states including Lebanon. The Arab East, of which the small Mediterranean country was an inseparable part, witnessed the vibrant anticolonial politics of the 1950s and ’60s atrophy under a variety of repressive Arab regimes during the Cold War. Lebanon had already experienced a short civil war in 1958.

But the true calamity in the Arab East had occurred a decade before that, when Palestine was shattered by Zionists bent on establishing an exclusively Jewish state. In their drive to realise this ethnoreligious fantasy, they plunged the region into instability and war. The Zionists expelled most of the Palestinian natives from their lands and homes in 1948 and confiscated their property. In response, long-established Jewish communities across the Arab East found themselves scapegoated and imperilled. Since then, Arabs and Jews have been represented as eternal ontological foes as if their bitter contemporary political struggles rehearsed allegedly ancient religious conflicts. How intriguing then to read a poem titled ‘A Lesson from the Zionist Movement’ composed by my grandfather Anis and published in March 1914 in the journal Al-Kulliyya of the Syrian Protestant College – today the American University of Beirut (AUB).

The opening stanzas speak to a time when the word ‘Zionism’ in Arabic (Al-sahyuniyya) had not been completely tainted by the Zionist movement’s later deeds. The poem acknowledges the industriousness of the Zionist colonists who had arrived in Palestine from Europe at a moment of Arab decline. The lesson my grandfather drew from the Zionist movement was two-fold: the first was that the determination and agency of Zionists to revive themselves might spur the Arabs ‘to match them in their endeavour and enterprise’. This exhortation to progress perhaps reflected my grandfather’s distinctly Protestant Arab modernism, which was influenced heavily by American missionary institutions and culture.

But the urgent call for the Arabs to join the caravan of modernity also reflected a ubiquitous trope of the ecumenical Arab intellectual and cultural renaissance known as the nahda. For that same Zionist determination – and here was the more important lesson my grandfather drew – ultimately threatened to overwhelm the Arabs who needed to stop lamenting their glorious past and overcome their present pitiable condition. ‘Is it any wonder that the nation of Moses has settled on our shores, ploughing the land diligently,’ he wrote. My grandfather saw that European Jews had galvanised a Jewish awakening and then an organised Zionist movement. Yet he also alluded to the danger that the well-funded colonists posed to the Arabs of Syria who were still ‘asleep’. He was adamant that God had blessed the Arabs with a land from which valiant men had emerged and a beautiful language that transcended religious difference. It was for the Arabs to choose whether they would ultimately give way before these zealous outsiders or realise that they had it within themselves to build a free and dignified future. ‘If you are ultimately humiliated,’ he concluded addressing his own Arab people, ‘do not say it is fate and divine decree that had concealed themselves in the passage of time.’

My grandfather contributed to an incongruent early Arab archive that was still trying to make sense of Zionism and its relationship to a fading Ottoman world. There was little reason for my grandfather, or for Muslims and Christians across the Levant, to take issue with the religion of Judaism itself, or the desire for a revitalised Jewish cultural or spiritual communalism. Coexistence, after all, was deeply entrenched in the Arab East. Four centuries of Ottoman rule had not introduced a shared world between Muslims and non-Muslims. Rather, it had complicated a tradition that had been in place since the rise of Islam.

Although Islamic law privileged Muslims over non-Muslims in an empire ruled by Ottoman Muslim sultans, Christian and Jewish communities were integral parts of a diverse urban fabric. They existed in every corner of the Empire and, in the Arab East, Eastern Jews and Christians of the Empire spoke Arabic. In contrast to Europe, Jews were not singled out for persecution in the Ottoman Empire, which did not seek to make all its subjects practise the same faith or even share the same language or culture. At the Empire’s end, its leaders persecuted and massacred Armenians and hunted down Arab nationalists. But there was no ‘Jewish Question’ in the Ottoman Empire, nor was there a corresponding racialised antisemitism.

Herzl thought the native Arabs unworthy of Palestine itself

There is a reason that Zionism emerged in Europe and not in the Ottoman world. Every major Zionist leader was European, for it was in European cities and towns that the noxious combination of nationalism and antisemitism drove some Jews to dream of establishing a separate nationalist state. There was no menacing imperative driving Ottoman, Eastern or Arab Jews toward a scheme to reconstitute multireligious Palestine into a Jewish ethnoreligious nationalist state. Inevitably, that a minority of European Jews dreamt these dreams in the high era of Western racism and colonialism shaped how they thought about fulfilling them.

Theodor Herzl, the Viennese founding father of political Zionism, eventually landed on Palestine as the location of his Jewish state not simply because in it had unfolded the great stories and symbols of the Jewish faith and history; he identified it also because he belonged to a European world in which the presence of natives was thought irrelevant to consequential history and destiny. In his Zionist tract Der Judenstaat (1896), Herzl wrote: ‘We should there form a portion of a rampart of Europe against Asia, an outpost of civilisation as opposed to barbarism.’ Insofar as Herzl and other leading Zionist ideologues thought about the native Arabs at all, they considered them wholly incapable of developing themselves, and certainly unworthy of Palestine itself. They viewed them as a simple, apolitical, passive peasant population, and suggested that, through economic cooperation, these Arabs would sooner or later reconcile themselves to colonial Zionism in Palestine.

Herzl’s fantasies lay at the heart of a well-known story of modern Zionism, which inserted itself into a polyphonic Ottoman and Arab landscape. Less known is how many Muslim, Christian and Jewish Arabs initially grappled with Zionism, trying to make sense of it, understand it, sometimes after meeting Zionist representatives who spoke of the need for friendship and cooperation between ‘Arabs’ and ‘Jews’ without ever disclosing the ultimate goal of the organised European-led Zionist movement in Palestine. Like my grandfather Anis, some educated Arabs were initially impressed with the apparently modern methods of the Zionists but, like him, they were quick to understand the implications for the Arabs of Palestine. Yusuf Diya’ al-Khalidi, the Muslim Jerusalemite and Ottoman Arab mayor of Jerusalem, sent a letter to the chief Rabbi of France in 1899, asking him to forward it to Herzl, in which he acknowledged that the idea behind Zionism was ‘in theory a completely natural and just idea’ to combat European antisemitism, but its implementation in multireligious Palestine was not. Khalidi expressed his growing concern about the colonial dimension of Zionism in Palestine.

As long as the Ottoman Empire existed, the idea of an actual Jewish state seemed remote. Zionists debated among themselves the viability, necessity, form and implications of a Jewish state in Palestine, especially as those who travelled to Palestine recognised that the reality of a large native Arab population posed an obvious conundrum to the nationalist project to establish a Jewish state. The advent of more and more Jewish colonies, sometimes built on land purchased from absentee Arab landlords, began to arouse sustained Palestinian suspicion. The more the Arabs learned about Zionism, the more alarmed they grew.

After 1904, a new wave of ardent colonists from eastern Europe and Russia rejected Arabic and sought little integration into local society. In 1911, Najib Nassar, the owner and publisher of the Arabic newspaper Al Carmel in Haifa (whom my grandfather had befriended when both were students in Beirut), wrote a short treatise on Zionism. Nassar warned his readers about the modern organisation, motivation and seriousness of the political programme of Zionism. He insisted that he would never have opposed Jewish immigration had Zionism been free of political ambition. Nassar acknowledged how Herzl had worked hard to inspire Jews from around the world to embrace Zionism, but he said that the Zionists did not truly want to ‘Ottomanise’ – rather they wanted to build their separate nationalist state in Palestine, and so had to be resisted urgently.

Also in 1911, Ruhi al-Khalidi, the nephew of Yusuf Diya’, gave a speech in the Ottoman parliament in Istanbul praising Jews but warning that Zionism would bring an imminent breakdown of relations between Arabs and Jews. And in 1913, the Cairo-based journalist and author Jurji Zaydan visited Palestine and also saw the writing on the wall. Commenting in his ecumenical journal Al-Hilal, Zaydan repeated Nassar’s stark warning to the Arabs about the danger of Zionist colonisation of Palestine.

For Muslim and Christian Arabs of all stations and locales, Zionism unquestionably needed translation. Almost everything about Zionism screamed foreignness: the languages the colonists and immigrants spoke; their nationalist ideology; their dress; their settlements; and the relentless efforts of its European leaders – such as the German social scientist and social Darwinist Arthur Ruppin who worked with the World Zionist Organization and the Jewish National Fund to plan the ‘scientific’ colonisation of Palestine – to segregate ‘Jews’ from ‘Arabs’. For these reasons, educated Arabs left a significant record of observations and thoughts that often distinguished between Zionists and native Jews. In a way that colonial Zionism refused to do, Ruhi al-Khalidi and my grandfather, and many others such as the Jerusalemite educator Khalil Sakakini, could distinguish between a major religion that constituted the shared foundation of the three great monotheistic religions and a political movement that emerged out of one aspect of the Jewish experience in the bitter nationalist climes of central and eastern Europe.

Arab Jews, however, had a more difficult intellectual reckoning with the early iterations of Zionism in Palestine. Zionists spoke adamantly about representing the entirety of the Jewish people. Unlike Christian and Muslim Arabs, Arab Jews wrestled intensely with Zionism as a form of self-identification, not as a foil to their own aspiring modern rejuvenation. Some native Jews saw in the idea of Jewish revival in Palestine an important avenue of Jewish communal self-expression within the Ottoman Empire that had long valorised religious diversity. Others saw it as an alien intrusion that segregated them from their fellow Arabic-speaking Muslim and Christian compatriots.

The organisation, funding and colonial confidence among many Zionists settling in Palestine instigated a cultural and institutional struggle over who truly represented the Jewish community in Palestine and what the future of Jewish life there would be like. This intra-Jewish conflict split most of the newly arrived Ashkenazi European Zionist colonists from Sephardic Jews long settled in the Ottoman Empire and, of course, from other Middle Eastern Jews who were not Ashkenazi and not necessarily Sephardic. These lines were not uniformly rigid, for there were native Ashkenazi Arab Jews born in Palestine who refused colonial Zionism, just as many Sephardic Jews who embraced it from the beginning and who worked for or donated to various Zionist institutions. Jews debated Zionism in communal councils, schools, including those of the French-funded Alliance Israélite Universelle, in the multilingual Jewish press, and in their homes. The struggle ultimately impinged upon all Eastern Jewish communities across the Maghrib and Mashriq and into Salonika and other major cities of the Empire.

Reconciliation between Arabism and Zionism wasn’t a diversionary gambit to mollify increasing Arab concern

Did Jews belong to an ecumenical nation with compatriots of different religions, or fundamentally only to a political nation with other Jews: this basic question dominated the political itinerary of Zionism in Palestine. The European Zionist leaders knew their answer and worked, especially after the inaugural World Zionist Congress in Basel in 1897, to advocate for eventual Jewish sovereignty in or over Palestine. More immediately, they strove for unimpeded (and ultimately mass) immigration of European Jews to Palestine despite native Arab wishes, and they purchased land there to establish the material basis for a Jewish state in Palestine.

For Arab Jews, the question of Zionism was not so simple. The feminist journalist Esther Azharī Moyal and her husband, the journalist Shim‘on Moyal, as well as Nissim Malul, another journalist, struggled with the relationship between Arabism and Zionism. Unlike the European Zionists, they spoke Arabic and valued Arab culture. Like many of their Arab Jewish compatriots in Syria and Egypt, Malul and the Moyals saw in, or convinced themselves that, Zionism was a cultural and national expression that could coexist with the multireligious reality of Ottoman Palestine. To honour their commitment to a shared world, the Moyals even named their first-born son after their friend Abdullah Nadim, a childless Egyptian nationalist writer. For them, reconciliation between Arabism and Zionism did not appear to be merely a diversionary gambit to mollify increasing Arab concern, as it was for leading European Zionists. The latter included Nahum Sokolow, who visited Beirut and Damascus in 1914 to meet prominent Arab intellectuals and public figures, and Victor Jacobson, who as a manager of the Zionist Anglo-Palestine Bank in Istanbul, sought to convince a young Arab journalist As‘ad Daghir of the possibility of cooperation between ‘Arabs’ and ‘Jews’.

Malul, for example, wrote in 1913 that ‘in the role of the Semitic nation we must base our nationalism in Semitism and not blur with European culture, and through Arabic we can found a real Hebrew culture. But if we bring into our culture European foundations then we will simply be committing suicide.’ And yet Malul committed himself to working for a European-dominated Zionism. He joined the Zionist Office in Jaffa in 1911, at the same time as he was a correspondent for the Arabic Cairo-based newspaper Al-Muqattam. Together with the Moyals, he consistently sought to rebut anti-Zionism in the Arabic press and to reassure Arab readers that Zionism was indeed compatible with Arab national aspirations. On the eve of the First World War, however, revivified Hebrew, not Arabic or Turkish, was rapidly being made the dominant language of the multilingual Jewish community in Palestine that was itself rapidly coalescing around a Jewish national identity that clearly excluded Palestinians.

Whatever their early admiration for aspects of Zionist modernity, Muslim and Christian Arabs banished them from their collective memory after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire following the First World War. The Balfour Declaration of November 1917, followed by the imposition of a British mandate in Palestine in 1920, consecrated an overtly colonial phase of Zionism. Both the British foreign secretary Arthur Balfour’s letter to the Zionist leader Walter Rothschild and Britain’s stated policy openly privileged the foreign European political project of a Jewish ‘national home’ over self-determination for native Arabs. Although British colonial officials proclaimed that they held the scales of justice in balance, they systematically drove apart Arabs and Jews in Palestine. Britain rejected the possibility of a secular national Palestinian identity, and ignored or crushed every instance of Palestinian resistance that sought to demonstrate such an identity.

British and Zionist flags fly over an Arab village. Photo taken between 1898 and 1930. Courtesy the Matson Collection at the Library of Congress

Colonial Zionism, meanwhile, waged an undeclared but open war on Arab Palestine. Zionists lobbied the British openly to allow unfettered Jewish immigration to Palestine irrespective of native wishes to lay the demographic foundation for their exclusive ethnoreligious nationalist state. They wanted to turn the native majority into a minority on its own land. ‘The brutal numbers operate against us,’ confided Chaim Weizmann, the Russian-born leader of the Zionist movement, to Balfour in 1918. Weizmann’s private letters express his racist contempt for ‘the Arab’ and disdain for anti-Zionist native Jews: there were too many Palestinians in Palestine to create a Jewish state and not enough native Jews who were committed to colonial Zionism. Weizmann worried that the ‘Arab problem’ might yet derail the territorial and political Zionist project in Palestine. He believed that whereas ‘friendship’ and understanding between Arabs and Jews were possible, they were conditional and secondary to the Zionist conquest of Palestine, and on a complete national separation between ‘Arabs’ and ‘Jews’. With British colonial protection, the Zionists built up segregated Jewish political, immigration, educational, labour, economic, land and social organisations. With each tangible proof of its success, colonial Zionism foreclosed the future of Arab Jews as a viable part of the Arab political community – beginning but not ending in Palestine.

The tragedy of Arab Jews was that their Arabness was instrumentalised by colonial Zionism

Malul began to work for the Zionist National Committee following the establishment of the pro-Zionist British mandate that lasted until 1948. The Zionist leadership in Palestine sought to collect information on the Arabs of Palestine and to propagandise among them. Like an increasing number of other Arab Jews, Malul cast his lot irrevocably with colonial Zionism. As individuals, they may have been socially intimate with other Arabs of different faiths, and even loved Arabic. Yet they also embraced the central historical premise of a collective colonial Zionism: that Palestine was the national land of the Jewish people. They located themselves in a political and racial hierarchy that consistently placed Ashkenazi European Jews on top, followed by the ambivalently incorporated Sephardic and other Middle Eastern Jews, and finally the non-Jewish native population that had no real place within the Zionist project.

During the 1930s and ’40s, the Zionist paramilitary Irgun bombed markets, public buildings and cinemas in a campaign of terror. Its most notorious act was the massacre of Palestinian civilians at Deir Yassin in April 1948. The Irgun created a unit made of Arab and Arabic-speaking Eastern Jews to infiltrate and terrorise the Arabs of Palestine. Colonial Zionism used Arab Jews to study, observe, inform on, manage and eventually help to dominate their former compatriots. And yet colonial Zionism, paradoxically, was premised on the total rejection of Jewish Arab being.

Arab civilians, watched by international forces, leaving Iraq al-Manshiyya, near today’s Kiryat Gat, in March, 1949 after the Nakba of 1948. Photo courtesy the collection of Benno Rothenberg/Israel State Archives

The tragedy of Arab Jews was that their Arabness was instrumentalised by colonial Zionism, which denied the legitimacy of their Arab Jewish identity. They were made – and made themselves – settler-colonials in a sea of contradictory circumstances. After the Nakba (the disaster of Palestinian displacement) of 1948, the Ashkenazi-dominated state sought to de-Arabise the mass of Arab Jewish immigrants who arrived in the newly created state of Israel. David Ben-Gurion, the first prime minister of Israel, shuddered at the thought that Arab Jews would turn the new state into another ‘Levantine’ country populated by what he and many other European colonists saw as inferior ‘primitive’ Eastern Jews. ‘We are alien to them and they are alien to us,’ Ben-Gurion said of these Jews whom he also considered too close to Arab culture, and Jews ‘only in the sense that they are not non-Jews’.

Although colonial Zionism demanded the historically novel nationalist separation of ‘Arab’ and ‘Jew’, its leaders publicly proclaimed that there was every possibility of rapprochement with the Arabs outside of Palestine – so long as they acquiesced to the abandonment of Palestine and the Palestinians. Weizmann, for example, hoped to come to terms with ‘the Hedjaz Arabs, who are more interesting than the local baystryuks’ [from байструк, Russian for ‘bastard’]. As the scale and political ambition of Zionist colonisation in Palestine became more apparent, however, so did the question of Palestine become a core element of modern Arab identity.

In 1919, the desperate Hashemite Prince Faysal was willing to sign a treaty of friendship between ‘Arabs’ and ‘Jews’ in London apparently drafted by Weizmann. Faysal was perhaps taken in by Weizmann’s assurances that no harm would come to the local Palestinian population. More likely, he wanted the Zionists to support his political ambitions in neighbouring Syria. A year later, the fantasy of this kind of friendship, unmoored as it was from the reality in Palestine and from the overwhelming sentiment expressed by Syrians more broadly in opposition to colonial Zionism, was shattered by Arab-Jewish clashes in Jerusalem precipitated by Zionist colonisation. By the time the great anticolonial revolt against the British mandate in Palestine erupted in 1936, Arab attempts to distinguish Jews from Zionists were increasingly overwhelmed by facts on the ground. The relentless Zionist insistence that a diverse Jewish people constituted a singular ethnoreligious political community made such a distinction both utterly vital and immensely difficult to sustain. Violent anti-Jewish Arab reactions to violent colonial Zionism and Western imperialism exacerbated a new and growing chasm between Arabs and Jews. History masqueraded as destiny.

Newly arrived Iraqi Jews at Lod airport, Israel, prior to their initial relocation in camps in May 1951.

My grandfather was travelling in the United States in 1948 when the Nakba occurred. It is not clear if Ustadh Anis remembered his poem of decades earlier; the memoir in which he recounts his trip does not mention it. Instead, he recalled his bewilderment at the extent of Zionist propaganda in the US over the question of Palestine. While en route back to Lebanon, he was dismayed to hear about the assassination of the Swedish UN mediator Count Folke Bernadotte by ‘the Zionists’. For almost all Arabs of that moment, whether they were Muslim or Christian, Sunni or Shi‘i, poor or rich – whether they lived in Morocco, Syria, Iraq, Yemen or Saudi Arabia – Zionism had become anathema to the same extent that the ‘Palestinian cause’ (al qadiyya al-filastiniyya) became a unifying idea.

The success of Zionism threatened the foundations of secular Arab unity and identity

My grandfather, for example, noted in his classic Literary Trends in the Modern Arab World (first published in the early 1950s), that ‘Palestine constitutes a general Arab national cause and as such Arabic literature in every part of the Arab world expresses deep sympathy for Palestine and is preoccupied by her fate.’ For the minority of Jewish Arabs who remained in the Arab world after 1948, the identification ‘Palestine’ was immensely complicated by Zionist efforts to cajole them to ‘return’ to Palestine, by propaganda, and by anti-Jewish scapegoating and violence in places such as Iraq. But it remained evident – a fragile thread to a past and possible future of solidarity that transcends ethnoreligious nationalism.

This Arab consciousness of the calamity of Zionism stemmed not from inveterate religious hatred on the part of Arabs against Jews, but rather from a profound shared sense of an unbearable and still ongoing injustice that demands restitution. After 1948, Arab leaders could not contemplate an open alliance with Zionism as Prince Faysal had done 30 years earlier. Some Arab intellectuals such as Constantine Zurayk frankly admitted the modernity of the Zionist project in Palestine, but saw it as a sinister system that had to be studied and defeated.

The success of Zionism threatened the foundations of secular Arab unity and identity because it privileged an ethnoreligious nationalism in a region rich in religious pluralism. This did not stop secret collusion between Arab leaders such as Faysal’s brother King Abdullah of Jordan and the Zionists, nor eventually, under massive US pressure and after several more wars broke the back of Arab armies, ‘peace’ treaties between fiercely antidemocratic Arab potentates dependent upon the US and nakedly racist Israeli leaders. My grandfather Anis’s death in 1977 occurred in the same year as the Egyptian president Anwar Sadat’s hugely controversial trip to Jerusalem, where he was met by Israel’s prime minister (and unrepentant former Irgun member) Menachem Begin who rejected completely Palestinian self-determination. When Sadat was assassinated a few years later in Cairo, celebratory gunfire erupted in Beirut where my grandfather had lived and died.

Arabs had long coexisted with compatriots of the Jewish faith; but that was fundamentally different from acquiescing to, let alone being compelled to accept, an ethnoreligious state violently built on what had always been, and what remains, a multireligious land. Like virtually all other Arabs, my grandfather Anis recognised the enormity of the injustice perpetrated in Palestine in 1948 but he also wondered if the Arabs were then sufficiently prepared, or in a position, to successfully reverse this injustice. He wrote that ‘Palestine has been torn from their hands. Now they struggle to regain portions of it. Should we issue a call to arms, or say that time will ultimately rule in favour of justice because time is the fairest of judges?’