In 1805, after a career participating in both the American and French revolutions, the swashbuckling international adventurer Francisco de Miranda approached the then president Thomas Jefferson, seeking US support for a military expedition to liberate his home country of Venezuela from Spanish rule. He appealed to Jefferson as a fellow American revolutionary, emphasising their shared hopes for the hemisphere, by quoting him Virgil:

The last great age foretold by sacred rhymes,

Renews its finished course; Saturnian times,

Roll round again, and mighty years began,

From this first orb, in radiant circles ran.

Miranda chose this passage as a reference to the Age of Saturn, described in ancient Roman mythology as a golden age of peace and abundance. The fall of monarchy and the rise of republicanism, Miranda told Jefferson, would mark ‘the revival of that age the return of which the Roman bard invoked in favour of the human race.’ His use of such classical imagery would have been instantly recognisable to Jefferson, not only as a demonstration of Miranda’s erudition but, even more importantly, as a gesture of solidarity in an international struggle for liberation.

Today, the neoclassical aesthetic is more likely to be associated with political conservatism, or even far-Right ethnonationalism. But contemporary debates about who ‘owns’ the classical past obscure the intellectual role it played in the emergence of modern democracy, and the reasons we are surrounded by its iconography in the first place. No ancient Roman ever set foot in Jefferson’s Virginia or Miranda’s Venezuela, yet the New World teems with simulacra of their ruins. For radicals during the Atlantic Age of Revolution, who called for an end to monarchy and aristocracy, the example of the ancient republics provided a shared symbolic framework for political values that crossed barriers of language, ethnicity and religion.

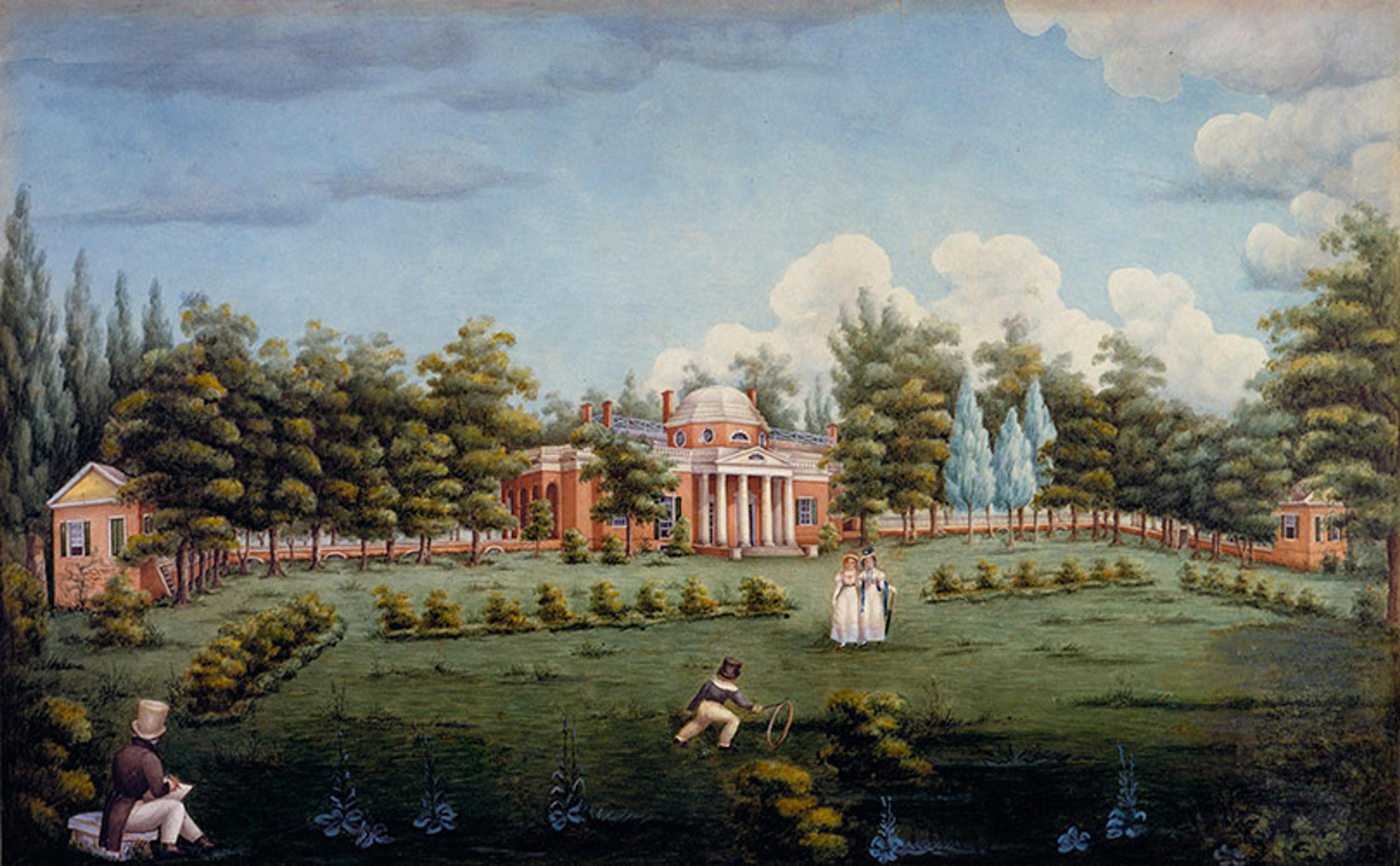

View of the West Front of Monticello and Garden (1825) by Jane Braddick Peticolas. Courtesy Wikipedia

Although the United States did not officially intervene in what would turn out to be a failed expedition to liberate Venezuela, Miranda did manage to secure (with a Jeffersonian wink and nudge) some number of private US ships and guns, and at least 200 US recruits. According to one of them, a New Yorker named James Biggs, Miranda’s Anglo American followers were convinced of ‘the glory and advantages of the enterprise’ in part by the general’s eloquent appeals to classical antiquity. ‘He took excursions to Troy, Babylon, Jerusalem, Rome, Athens, and Syracuse,’ Biggs recalled. ‘Men famed as statesmen, heroes, patriots, conquerors and tyrants, priests and scholars, he produced, and weighed their merits and defects.’ A shared knowledge of the classical canon created a cultural bridge between the New Yorkers and their Venezuelan comrades. In this way, the classical idiom served as a highly cosmopolitan medium for political expression, grounded in a heroic past to which both Anglo and Latin Americans could just as plausibly lay claim. Miranda successfully marshalled this imagery in order to frame the struggle for Venezuelan independence as a chapter in the ongoing liberation of all mankind – and as an opportunity for young men educated in the classical canon to finally undertake the kinds of heroic deeds they had until then only read about in books.

Contrary to some of its modern manifestations, the politicised neoclassicism of the Age of Revolution was not primarily a celebration of European identity or heritage. In fact, what made it so powerful as a political aesthetic was precisely its lack of ethnic specificity. The heroes of Greco-Roman antiquity were venerated, not as literal genetic ancestors, but as part of a kind of universal, mythical past, somewhat detached from actual history. With the professionalisation of fields such as archaeology in the later part of the 19th century, and the simultaneous rise of the eugenics movement, scholars were increasingly motivated to unearth ancient people’s physical remains in order to place them into modern racial categories. But, in the late-18th and early 19th centuries, classical learning played a very different intellectual role as a framework for interpreting human events. For early modern Europeans (and the subjects of their empires in America), the peoples of the ancient Mediterranean world occupied a unique imaginary space: they were familiar yet exotic, civilised yet brutal, virtuous yet pagan, somewhere between an ‘us’ and a ‘them’. This ambiguity was what made the classical canon intellectually stimulating and inspiring as a repository of supposedly universal political truths. In Miranda’s day, it was not yet quite sensical to ask whether the ancient Romans were ‘white’; they were Roman.

A key feature that distinguished neoclassicism from other aesthetic genres was its explicitly political character. The Rome of the early modern imagination, the inspiration for the philosophies of Niccolò Machiavelli and the plays of William Shakespeare, was the theatre of elite power struggles and popular unrest that provided the foundation for the taxonomy of politics itself. More than a particular ancient civilisation, it served as a transhistorical metaphor for civilisation in general. This Rome’s highest virtue was patriotism, and its gravest sin treason, for, without the hope of a Christian afterlife, its people led lives dominated by earthly affairs, amid a cosmos governed by capricious and unsympathetic forces. Even its great philosophers were lawyers, its great poets propagandists, its great martyrs politicians.

Julius Caesar, the dictator whose rise to power coincided with the collapse of the Roman Republic, was not just a demagogue and a tyrant; he was the tyrant, whose example made the very concept of tyranny legible. The senators who resisted him – Cato, who gutted himself with his own sword rather than beg for Caesar’s pardon; Cicero, whose severed head and hands were taken as trophies by Caesar’s lieutenant Mark Antony; Brutus, who at last stabbed the tyrant to death on the Senate floor – were the ultimate archetypes of political heroism and patriotic sacrifice. Their famous names and deeds transcended the flesh-and-blood historical figures to whom they were originally attached, becoming more like public-domain literary characters. Just as the poet Virgil served as Dante’s guide through hell in the Divine Comedy, the familiar dramatis personae of the classical canon were every schoolboy’s imaginary friends.

Early modern Europeans did not regard the ancient Greeks and Romans as part of some glorious European past to which they longed to return; their very pagan exoticism precluded this. Rather, the classical canon was thought to epitomise the full spectrum of human virtues and vices, providing both models to emulate and cautionary tales to avoid. By the 18th century, the stated rationale for prioritising the classical canon in university curricula was to inculcate civic virtue in the elite young men who would go on to lead public lives as clergymen, lawyers, physicians, military officers and imperial bureaucrats throughout the Atlantic world. A ‘classical education’ was a political and moral education, not an education in ancient history as such. Classical stories, such as the abdication of Cincinnatus or the assassination of Julius Caesar, were essentially secular parables, transmitting lessons about human psychology, conflict and power – stories that seemed especially applicable in intense, politically unstable times.

The era of bourgeois revolutions coincided with a general turn towards neoclassicism in architecture, visual arts, literature, music and theatre, which took place during the second half of the 18th century throughout Europe and its American colonies. In these early days of globalisation, the explosion of print culture and manufactured consumer goods prompted new concerns about the politics of fashion and good taste – ‘Buen gusto’ to the Bourbon reformers who sought to modernise the Spanish Empire, ‘antique taste’ to fashionable elites in England. With its emphasis on clean lines and symmetrical compositions, neoclassicism was seen as elegant, naturalistic and humane, against the busier and more extravagant baroque and rococo styles that had preceded it. In a strange paradox, the imitation of antiquity became an internationally recognised mark of modernity.

A republic needed statues and canvases in order to be made real in the minds of the people

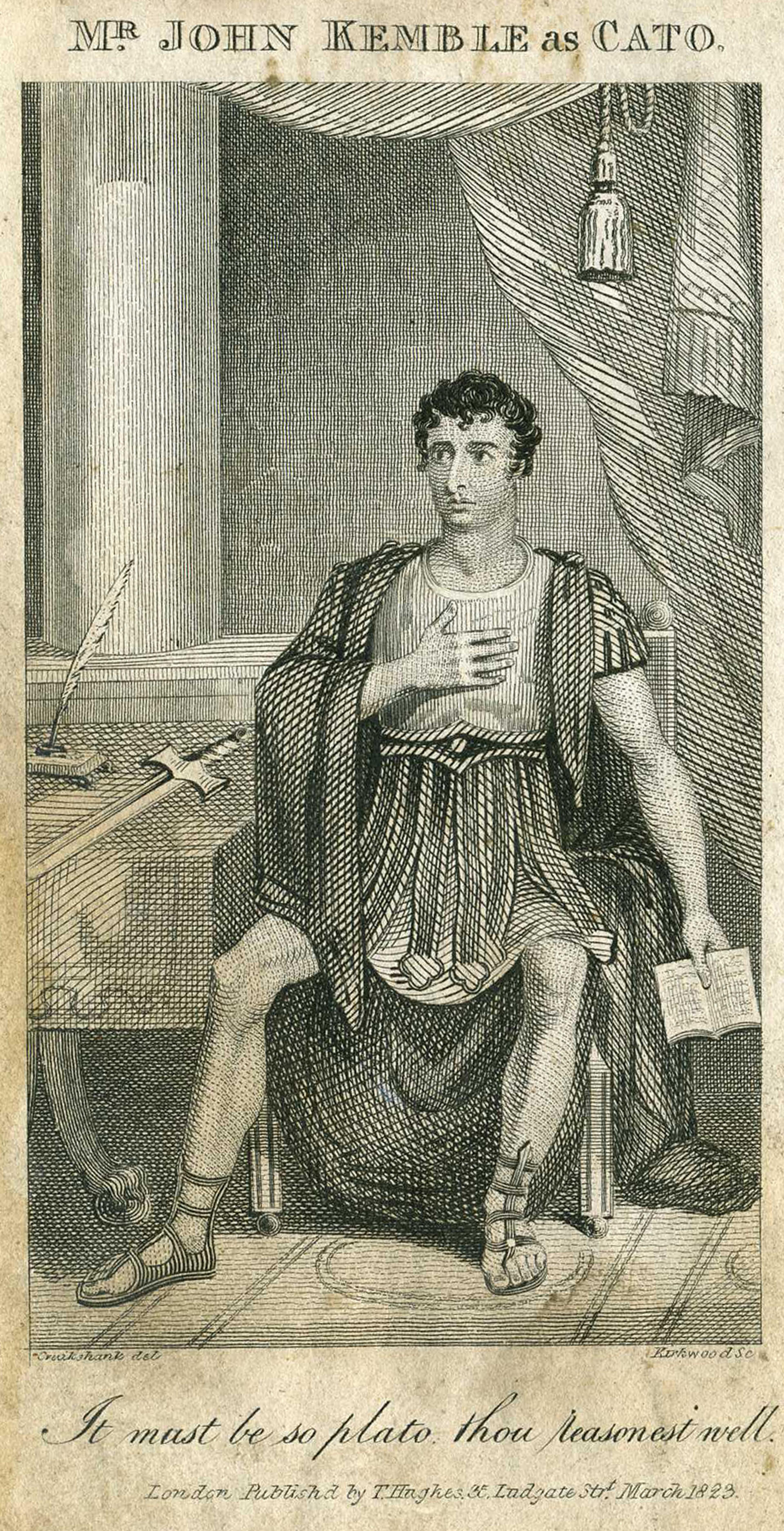

Revolution infused these cultural artefacts with new and urgent significance. Works such as Joseph Addison’s play Cato: A Tragedy (1713), which invited British aristocrats to see themselves in the titular Roman senator, achieved extraordinary popularity during the second half of the 18th century, reaching far beyond the elite audiences for whom they were originally intended. The image of Cato’s grisly suicide, his stoic willingness to eviscerate himself rather than live under Caesar’s tyranny, became synonymous with political martyrdom.

During the American Revolution, the play become so strongly identified with the cause of independence that George Washington’s troops staged their own production of it at Valley Forge. It so infused the popular culture that many of the American Revolution’s most famous slogans – including Patrick Henry’s cry of ‘give me liberty or give me death’ and the patriot spy Nathan Hale’s lament that he had ‘but one life to lose for my country’ – were actually paraphrased from lines of dialogue spoken by Addison’s Cato. Crucially, the radical interpretation of Cato formed part of an international vocabulary of republican solidarity. A Spanish translation of the play by Bernardo María de Calzada, entitled Catón en Utica (1787), was staged at patriotic festivals and Independence Day celebrations throughout Gran Colombia and Peru. When the Argentine revolutionary Bernardo de Monteagudo wrote of their common fight for independence from Europe in 1812, he called for Americans North and South to ‘renew the sacrifice of Cato’.

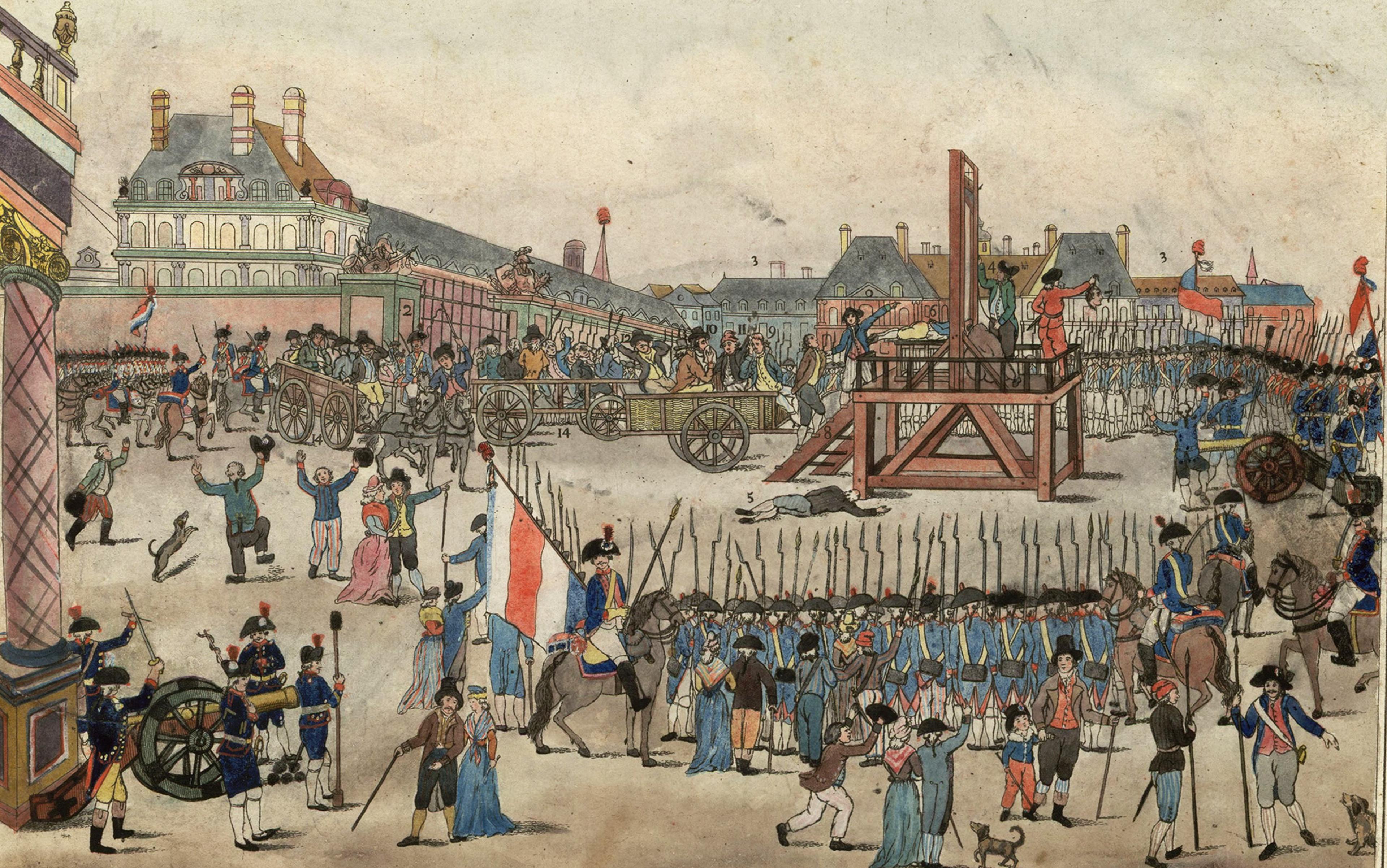

The Jacobins, the anti-royalist faction who played a leading role in the French Revolution, embraced neoclassicism, not because of any necessary connection with revolutionary politics, but because it was the one pervasive elite aesthetic that readily lent itself to a revolutionary interpretation. The striking canvases of the neoclassical painter Jacques-Louis David, for example, were originally commissioned by members of the French nobility; only retroactively, once David himself had thrown in with the Jacobins, did he receive the title of ‘the painter of Brutus and the Horatii, the patriot and Frenchman, whose genius anticipated the Revolution’. Intensely conscious of both the domestic and international implications of their aesthetic choices, the revolutionaries thought carefully about what a free and enlightened state should look like. Denouncing ‘the ridiculous hieroglyphs’ of monarchy and aristocracy, the legislature of the First French Republic called for new symbols capable of ‘grabbing hold of the senses’ in order to promote the proper mode of civic consciousness. A republic needed signs and seals, songs and slogans, statues and canvases, in order to be made real and present in the minds of the people. The question became what kinds of symbols reproduced the irrationalism and decadence of the monarchy, and what kinds were truly republican.

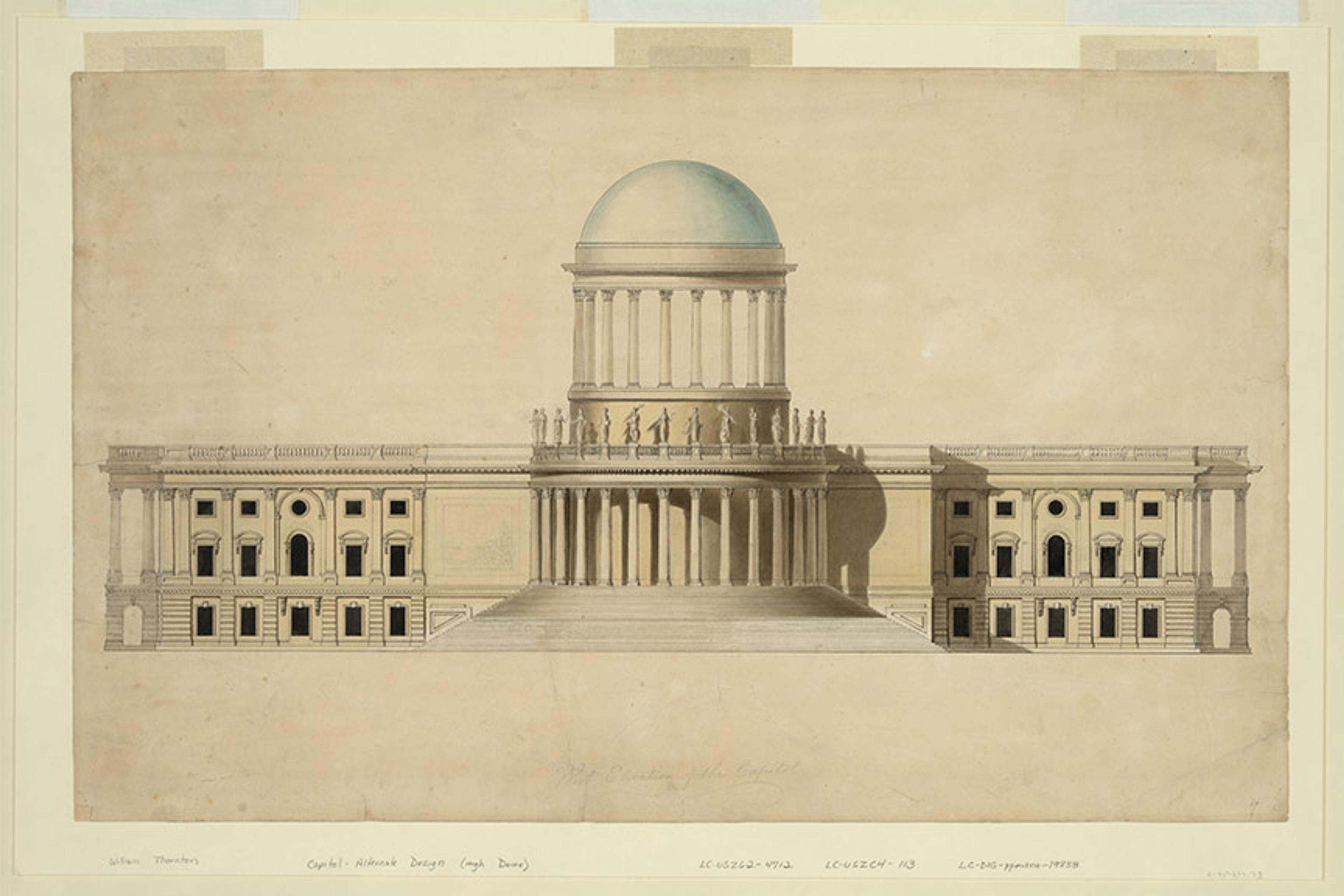

William Thornton’s initial ‘High Dome’ design for the US Capitol (c1797). Courtesy the Library of Congress

Neoclassicism, with its restrained grandeur and universalist appeal, was the obvious choice. The typical subject matter of neoclassical art – heroic figures and scenes from history, idealised nude bodies in strong, serious poses – seemed to stand in stark contrast with the pastel frivolity of the Ancien Régime. As a political aesthetic, neoclassicism promoted the values of courage, austerity and patriotic sacrifice, as well as ideals of reason, progress and human achievement associated with the Enlightenment. ‘The models of antiquity,’ according to Jefferson, provided timeless examples of good taste, because they had received ‘the approbation of thousands of years.’ It was with these principles in mind that, in 1792, he oversaw the design of the US Capitol Building, whose columned edifice would set the tone for the future construction of Washington, DC.

Revolutionary governments in the US, France, Haiti and throughout Latin America faced a similar set of dilemmas about how to represent themselves in the absence of the familiar trappings of monarchy and aristocracy. Each unsteady new republic had to strike the right balance between simplicity and grandeur, to seem authoritative but not tyrannical, prosperous but not decadent, enlightened and modern, yet rooted in venerable tradition. When revolutionaries searched the past for non-monarchical models of civic life, the ancient Greek city-states and, to an even greater extent, the Roman Republic seemed like the only political legacy worth hearkening back to.

Much like the socialist realism of the 20th century, the neoclassicism of the Age of Revolution was an international political aesthetic that prized reason, humanism and universalism, while disdaining luxury, decadence and baroque abstraction. Like Marxism, with which it shares a great deal of its intellectual genealogy, the ideology of civic republicanism provided a secular, materialist, conflict-driven theory of history. It emphasised the drive of human beings to pursue their own self-interest, and saw the task of politics as balancing the interests of various classes and factions of society in order to achieve a common good. The associated artworks might appear either inspiring or thuddingly didactic, depending on one’s personal preferences. (Marble statues of Washington’s head on the buff body of Zeus and portraits of the Venezuelan revolutionary leader Simón Bolívar receiving a crown of laurel from the winged goddess of victory certainly have about the same level of subtlety as a Soviet propaganda poster.) But, for the civic republicans of the late-18th and early 19th centuries, a shared neoclassical aesthetic helped to render ideological abstractions such as ‘popular sovereignty’ or the ‘common good’ in a rich visual language of columned temples, urban masses, togaed senators and laurelled heroes. Neoclassicism lent the emerging democratic nation-state its first distinctive symbolic vocabulary – the public spectacle of the agora, updated for the age of print media and popular opinion.

George Washington (carved after 1844) by Hiram Powers. Courtesy the Met Museum, New York

California (1858) by Hiram Powers. Courtesy the Met Museum, New York

Triumphal arch at Grays Ferry, Philadelphia, honouring George Washington on his inaugural journey in 1789. Courtesy the New York Public Library

One important example of such borrowed spectacle was the Roman triumph. In ancient Rome, a returning general would parade through the city with his spoils and captives in order to receive his ceremonial crown of laurel, a symbol of victory dating back to King Romulus. Upon his election to the presidency in 1789, Washington received a triumph as he passed through Philadelphia on the way to his inauguration in the temporary US capital of New York City. Designed by the portrait artist Charles Willson Peale, the ceremony featured Washington riding on horseback through a series of triumphal arches, with Peale’s own daughter waiting to drop the crown of laurel onto his head from above as he passed underneath.

Ordinary Haitians embraced the Phrygian cap, a hat worn by emancipated slaves in ancient Rome

In 1800, the Haitian revolutionary leader Toussaint Louverture enjoyed a similar triumphal reception as he entered the port city of Cap-Haïtien, complete with the construction of a victory arch, speeches comparing him with Hercules and Alexander the Great, and a woman noted for her ‘exceptional beauty’ placing the crown of laurel upon his head. Bolívar did them both one better upon the liberation of Caracas in 1813, riding into the city on a chariot and bowing his head to receive his laurels from a group of young women dressed in white. Performed before live audiences of thousands, such displays became part of the leaders’ far-reaching media images, reproduced in national and international newspapers in a way that would have been impossible in ancient times.

Louverture, for example, was widely hailed as a modern Spartacus, after the Thracian gladiator who lead a massive slave rebellion in ancient Rome. Conscious of its international significance, Louverture himself embraced the comparison. As far from Haiti as New York, the image of him as a modern Spartacus appeared in the African American newspaper Freedom’s Journal. To compare the Haitian Revolution, the greatest modern slave revolution, with the revolt of Spartacus was to universalise it, to place it within a global history. This classicisation was befitting of such earth-shattering events, which struck fear into the hearts of slave owners across the Atlantic world. It was precisely because the classical archetypes were somewhat untethered from actual history, unencumbered by modern notions of ‘race’, that they provided useful models of politics and human nature in general. In a world still dominated by European empires and their elaborate systems of hierarchy and deference, neoclassicism helped to render the unprecedented political developments of the late-18th and early 19th centuries comprehensible, visualisable in familiar terms. The legend of Spartacus offered some idea, some glimpse, of what universal liberation and mass participation might look like.

Although championed by political elites, the neoclassical mode of political expression was by no means limited to those who had studied Greek and Latin in college. Ordinary Haitians embraced the Phrygian cap, a hat worn by emancipated slaves in ancient Rome, as a symbol of their own emancipation, gathering in town squares throughout the country to plant commemorative liberty trees that were marked by a Phrygian cap on a pike or pole. Gabriel Prosser, the leader of a slave rebellion in Richmond, Virginia in 1800, designed a silk banner that read ‘Death or Liberty’ – an arguably pessimistic inversion of Cato’s cry of ‘Liberty or Death’. The community of Manuel Macedonio Barbarín, a formerly enslaved veteran of the May Revolution in Buenos Aires in 1810, placed the ‘laurel of honour’ upon his grave, performing their own humble triumph. In 1822, when Juan Bautista reflected on the largest Indigenous uprising in the history of the Spanish Empire, led by his half-brother Túpac Amaru II, he concluded that the great Andean rebel, executed by Spanish authorities in 1781, was the true modern Cato. His Indigenous and mestizo followers, not the Spanish elites, were the ones who embodied ‘the courage of Scævola and the virtue of Socrates’.

The Age of Revolution gave us politics as we know it. We can trace the origins of modern mass media, mass parties and mass movements, which structure so much of modern political life, to the period that produced not only the first consumer boycotts and the first widely circulated newspapers, but also the words and concepts of modern ‘ideology’, ‘public opinion’ and ‘the news’. The metaphor of the return of republican antiquity helped radicals throughout the Atlantic world think through the problems of their own age – an age newly structured by forms of media and political participation that did not exist and could not have existed in ancient times. In their self-conscious efforts to shape public opinion through political aesthetics, the civic republicans of the 18th and 19th centuries were a lot less like the ancient Romans they sought to emulate, and a lot more like us media-saturated moderns. And yet, in their utopian aspirations, their historical imagination, their impulse towards universalism, they were capable of thinking about the world in ways that we, in our age of fracture, have perhaps forgotten.