Good conversation mixes opinions, feelings, facts and ideas in an improvisational exchange with one or more individuals in an atmosphere of goodwill. It inspires mutual insight, respect and, most of all, joy. It is a way of relaxing the mind, opening the heart and connecting, authentically, with others. To converse well is surprising, humanising and fun.

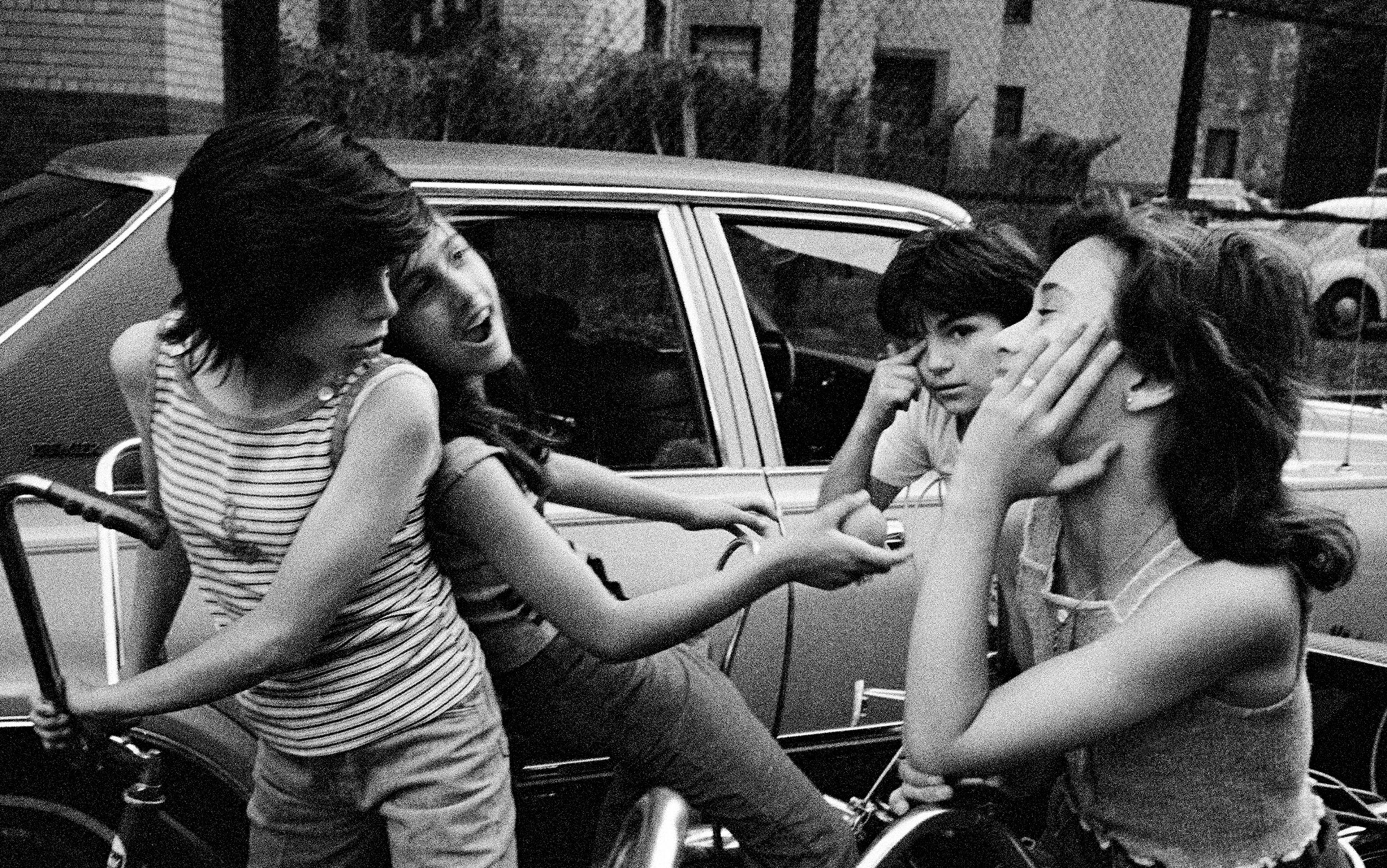

Above is my definition of an activity central to my wellbeing. I trace my penchant for good conversation to my family of origin. My parents were loud and opinionated people who interrupted and quarrelled boisterously with each other. I realise that such an environment could give rise to taciturn children who seek quiet above all else. But, for me, this atmosphere was stimulating and joyful. It made my childhood home a place I loved to be.

The bright, ongoing talk that pervaded my growing up was overseen by my mother, a woman of great charm and energy. She was the maestro of the dinner table, unfailingly entertaining and fun. We loved to listen to her tell stories about what happened to her at work. She was a high-school French teacher, a position that afforded a wealth of anecdotes about her students’ misbehaviour, eccentric wardrobe choices, and mistakes in the conjugation of verbs. There were also the intrigues among her colleagues – how I loved being privy to my teachers’ peccadillos and romantic misadventures, an experience that sowed a lifelong scepticism of authority. My mother had the gift of making even the smallest detail of her day vivid and amusing.

My father, by contrast, was a very different kind of talker. A scientist by training and vocation, he had a logical, detached sort of mind, and he liked to discuss ideas. He had theories about things: why people believed in God, the role of advertising in modern life, why women liked jewellery, and so on. I recall how he would clear his throat as a prelude to launching into a new idea: ‘I’ve been thinking about why we eat foods like oysters and lobster, which aren’t very appealing. There must be an evolutionary aspect to why we have learned to like these things.’ Being included in the development of an idea with my father was a deeply bonding experience. The idea of ideas became enormously appealing as a result. And though my father was not an emotional person – and, indeed, because he was not – I associated ideas with our relationship, and they became imbued with feeling.

Perhaps my family was exceptional in its love of conversation, but all families are, to some extent, learning spaces for how to talk. This is the paradox of growing up. Language is learned in the family; it solidifies our place within it, but it also allows us to move beyond it, giving us the tools to widen our experience with people very different from ourselves.

My family inculcated in me a life-long love of conversation – of sprightly, sometimes contentious, but always interesting talk that allowed me to lose myself for the space of that engagement. My pleasure in conversation has led me to think about the activity at length, from both a psychological and philosophical perspective: what makes a good conversation? What role has conversation served in history? What does talk do for us, and how can it ameliorate aspects of our current, divided society, if pursued with vigour and goodwill?

Sigmund Freud began his groundbreaking work as the father of psychoanalysis by postulating that his patients’ symptoms were physical responses to traumatic events or taboo desires dating from childhood. He found that if these people could be encouraged to talk without inhibition – to free-associate on what they were feeling – they would eventually find the source of their problems and the cure for what ailed them. With this in view, he made talk central to his therapeutic method – hence, the ‘talking cure’.

Although many of Freud’s theories have since been refuted, the talking cure has endured. Clinical psychologists still recommend talk therapy as a treatment for both generalised anxiety as well as more severe mental health issues. And though Freud’s talking cure is not, by any stretch, a real conversation – the patient talks, the analyst listens and strategically intervenes – the phrase ‘talking cure’ strikes me as a useful one in referring to the nature and use of conversation in our lives.

The need for conversation is one that many people have not fully acknowledged, perhaps because they have not had occasion to do enough of it or to do it well. I am not suggesting that, in conversing, we serve as each other’s therapists, but I do believe that good talk, when carried on with the right degree of openness, can not only be a great pleasure but also do us a great deal of good, both individually and collectively as members of society.

For me, one particularly useful concept derived from Freud’s talking cure is the idea of transference. In the course of therapy, Freud found that some patients felt that they had fallen in love with their therapists. Since he believed that all love relationships recapitulate what occurs within one’s family of origin, he saw these patients’ infatuation as a repetition of earlier, intense feelings for a parent that could now be analysed and controlled – directed toward more productive and transparent ends.

A relationship can be over once consummated in sex. But friendships are never over after a good conversation

I think this idea is relevant to our understanding of conversation as an important activity in connecting with others. Putting aside the familial baggage that Freud saw as accompanying transference, a deep sense of affection seems to be, always, part of good conversation. Surely readers can identify with that welling up of positive feeling – that almost-falling-in-love with someone that we engage with in an authentic way. I have felt this not only for friends and even strangers with whom I’ve had probing conversations but also for whole classes of students where it can seem that the group has merged into one deeply lovable and loving body.

If love can be understood as important in conversation, so can desire, another element central to Freud’s thought. Sexual desire has its consummation in the sex act (a form of closure that accounts for why a poet like John Donne, among others, used ‘death’ to refer to sexual climax). Conversation, by contrast, does not consummate; it merely stops by arbitrary necessity. One may have to get across town for a meeting, pick up a child from school, or generally get on with the business of life. Such endings are in medias res, so to speak, or mid-narrative. I find it interesting that a relationship can sometimes be over once the partners have consummated it in sex. But friendships are never over after a good conversation; they are sustained and bolstered by it.

The search for satisfaction by our desiring self seems to me at the heart of good conversation. We seek to fill the lack in ourselves by engaging with someone who is Other – who comes from another position, another background, another set of experiences. Everyone, when taken in a certain light, is an Other by virtue, if nothing else, of having different DNA. To recognise this difference and welcome it is the premise upon which good conversation is built.

Conversation also helps us deal with the human fear of the unexpected and the changeable. Talk with others allows us to practise uncertainty and open-endedness in a safe environment. It offers exercise in extemporaneity and experiment; it deconverts us from rigid and established forms of belief. There is no better antidote for certainty than ongoing conversation with a friend who disagrees.

Good conversation is an art that can be perfected, and the best way to do this is to converse regularly with a variety of people. As the fat man says to Sam Spade in Dashiell Hammett’s novel The Maltese Falcon (1930): ‘Talking’s something you can’t do judiciously unless you keep in practice.’

The next best thing to practising conversation is reading those authors whose writing seems to channel the spirit of good conversation or give insight into its mechanics.

‘How can life be worth living … which lacks that repose which is to be found in the mutual good will of a friend? What can be more delightful than to have someone to whom you can say everything with the same absolute confidence as yourself’? wrote the lawyer and orator Marcus Tullius Cicero, who lived in ancient Rome in the 1st century BCE.

Expanding on the subject hundreds of years later, in the 16th century, was Michel de Montaigne, whose pioneering work in the personal essay form is, in its intimate and meandering style, a tribute to his love of conversation. ‘[I]f I were now compelled to choose,’ he writes in the essay ‘On the Art of Conversation’, which addresses the subject directly, ‘I should sooner, I think, consent to lose my sight, than my hearing and speech’. One feels the pathos of this statement, given that Montaigne lost his most cherished friend, Étienne de la Boétie, at an early age and never ceased to mourn that loss. Indeed, some feel that the loss of La Boétie, by depriving Montaigne of his companion in conversation, accounts for the Essays, written to fill that void.

The 18th century was a great age of conversation; Samuel Johnson, Jonathan Swift, Oliver Goldsmith, David Hume, Joseph Addison and Henry Fielding are among the venerable authors of the period to provide commentary on what they considered to be important for good talk. The Literary Club in London, frequented by many of these luminaries, is said to have been organised in 1764 to help Johnson from succumbing to depression – through conversation, among other things.

Conversation was one of the activities that an aspiring gentleman was expected to learn

The book The Words That Made Us (2021) by Akhil Reed Amar, on the founders of the American Republic, makes the point that the American Revolution was successful in mobilising disparate people to its cause as a result of long and probing conversations among constituents across the colonies. The British were fated to lose the war, Amar argues, because George III refused to listen, let alone converse with his American subjects.

In the 19th century, especially in the United States where shaping the self alongside shaping the country became something of a national obsession, conversation was one of the activities that an aspiring gentleman was expected to learn. We see publication of numerous etiquette books during this period, with titles like Manners for Men (1897); The Gentleman’s Book of Etiquette and Manual of Politeness (1860); and Hints on Etiquette and the Usages of Society: With a Glance at Bad Habits (1834) – all of which give guidance on conversation, though mostly of a utilitarian kind.

In the 20th century, the most notable figure in conversational self-help was Dale Carnegie, who created an entire industry out of teaching aspiring social and business climbers based on his most famous book, How to Win Friends and Influence People (1936). Carnegie began writing and giving courses in the 1910s, and his business survived him to grow into an empire (‘over 200 offices in 86 countries’, according to Forbes magazine in 2020) with supporting textbooks, online resources, newsletters and blogs that boast the tag line: ‘Training options that transform your impact.’ The message dovetails with the US myth of upward mobility and getting ahead. Carnegie’s self-improvement programmes have an offshoot in the self-realisation movements of the past few decades. A deluge of books in recent years link conversational skills to creative and relationship goals.

Having surveyed the abundant literature on conversation over the past two centuries, I find myself particularly charmed by a short but entertaining work, The Art of Conversation (1936) by Milton Wright. The book is full of citations from philosophy and literature, with thumbnail sketches of the ancient symposia and the ‘talkers of Old England’ while also exhaustively outlining conversational scenarios. In one case, the author describes a wife explaining to her husband how he should converse over dinner with his boss about his love of fishing and pipe smoking (Wright gives a verbatim account of the wife practising the conversation in advance of the dinner). In a chapter on ‘developing repartee’, Wright gives minute instruction on how to come up with a clever thought and insert it into conversation, advising:

It must be prompt.

It must seem impromptu.

It must be based upon the same premise that called it forth.

It must outshine the original remark.

The author advises practising imaginary scenarios so as not to suffer l’esprit d’escalier (carefully defined for the reader: ‘you think of the scintillating remarks you could have made back there if only you had thought of them’). The book has sections on using flattery, seeking an opinion, and how to ‘let him parade his talents’.

The book’s erudition combined with its unadorned acknowledgment of human vanity is charming. It is perhaps no coincidence that Wright reminds me of Baldassare Castiglione and Niccolò Machiavelli in his tone; they too were writing at a high point of their civilisation, were both astute about human nature but optimistic about how the individual could rise through deliberate study and strategy. And yet, even as Wright explains the levers by which one can manipulate others to become a ‘successful’ conversationalist, he ends on a surprisingly moving note that undercuts his own lessons: ‘If … you can forget yourself, then you have learned the innermost secret of the art of good conversation. All the rest is a matter of technique.’

I love this book for its unabashed willingness to put forward this contradiction. One can make one’s conversation better by following certain instructions about listening well and employing choice opening gambits, transitions and techniques for putting one’s partner at ease; one may even practise ‘repartee’. But the secret to conversation, that of forgetting oneself, cannot be taught. It is akin to the double bind that psychologists refer to when someone tells us to ‘be spontaneous’. The admonition goes against the grain of what is involved: a state of being that happens by being swept up in the ‘flow’ of the moment.

Ideally, one would want to converse with someone who is open and trusting, curious and good with words. But this is not always the case, and it often takes ingenuity and persistence to jump-start a good conversation. It is also a mistake to write off others simply because they don’t share your politics, religion or superficial values. While it is true that partisanship has become more pronounced in recent years, I don’t think this is irreparable.

Probing and spirited engagement can break apart ossified patterns of thought and bring to bear a more generous and flexible view of things. I have experienced the exhilaration of having an insight in the course of a conversation that didn’t fit with my pre-existing ideas, and of connecting with someone I might otherwise have written off. Most of us fear talking about important subjects with people we know disagree with us, much like we fear talking to people about the untimely death of a loved one. And yet these conversations are often, secretly, what both parties crave.

We discover new elements in our nature as we converse

Finally, there is the creative pleasure of conversation. If writing and speechifying can be equated with sculpture (where one models something through words in solitary space), conversation is more like those team sports where the game proceeds within certain parameters but is unpredictable and reliant on one’s ability to coordinate with another person or persons. Words in conversation can be arranged in infinite ways, but they wait on the response of a partner or partners, making this an improvisational experience partially defined by others and requiring extreme attentiveness to what they say. Also, like sport, conversation requires some degree of practice to do well. The more one converses – and with a variety of people – the better one gets at it and the more pleasure it is likely to bring.

Since conversation is, by definition, improvisational, it is always bringing to the fore new or unforeseen aspects of oneself to fit or counter or complement what the other is saying. In this way, we discover new elements in our nature as we converse. Over time, we incorporate aspects of others into ourselves as well.

One could say that in the flow of conversation the distance between self and Other is temporarily bridged – much as happens in a love relationship. It is sometimes hard to recall who said what when a conversation truly works – even when people are very different and stand ostensibly on different sides of issues.

Conversation is both a function of and a metaphor for our life in the world, always seeking to fulfil a need that is never fulfilled but whose quest gives piquancy and satisfaction, albeit temporarily and incompletely, to our encounters. In good conversation, there is always something left out, unplumbed and unresolved, which is why we seek more of it.

Adapted, in part, from Talking Cure: An Essay on the Civilizing Power of Conversation by Paula Marantz Cohen, published by Princeton University Press, 2023.