The parallels between the warnings from biologists about the loss of biodiversity and from anthropologists about the loss of cultural diversity are striking. In both cases, modernity – or globalisation if you wish – is the key cause of loss. This is a dual track worth pursuing because the main causes of loss in both cases are the same. Additionally, loss of diversity, whether cultural or biological, can be understood as a single phenomenon: the world is becoming flatter, with less complexity and fewer options.

These issues are not new. In Roger M Keesing’s textbook Cultural Anthropology: A Contemporary Perspective (1976), taught to undergraduates in the 1980s, one of the final chapters is titled ‘Response to Cataclysm’. It deals with the effects of state interventions and capitalist expansion on small-scale societies. Keesing was far from the first to raise the alarm. As early as 1839, James Cowles Prichard gave an address to the British Association for the Advancement of Science, where he spoke of the recent extension of ‘the progress of colonisation’ and its detrimental effects on local cultures. He concluded:

A great number of curious problems in physiology, illustrative of the history of the species, and the laws of their propagation, remain as yet imperfectly solved. The psychology of these [native] races has been but little studied in an enlightened manner; and yet this is wanting in order to complete the history of human nature, and the philosophy of the human mind. How can this be obtained when so many tribes shall have become extinct, and their thoughts shall have perished with them?

As to biological diversity, similar concerns inspired intellectuals and explorers to campaign for the establishment of national parks in the 19th century. Seeing nature not as an adversary to be overcome but as a treasure to be cherished, a broad palette of engaged citizens – in the United States, they included George Catlin, Henry David Thoreau, John Muir and Abraham Lincoln himself – saw unspoilt nature as inherently valuable, and in need of active protection.

Since the incipient environmentalist movement and the parallel concern among early anthropologists to document ‘vanishing cultures’, the visibility of human footprints and global cultural homogenisation have accelerated dramatically. Both as regards biological and cultural diversity, the threats are now massive and ominous. The main causes are the expansion of state and market forces, and the outcome can be described, in both cases, as a loss of flexibility. Whenever an insect species vanishes, or a language loses its last native speaker, the biosphere loses options.

A useful framework for understanding these related processes towards simplification and homogenisation – that is, towards the loss of options – is offered in the emerging field of biosemiotics, which views the biosphere – human as well as nonhuman – as a semiosphere: a system of communication defined by the ongoing, continuous exchange of signs. As its name suggests, biosemiotics offers a way of interpreting and studying nature, culture and their mutual entanglements by reading the way organisms influence each other through a continuous process of communication.

Let us begin by considering the reduction in flexibility, which we may define, following the ecological thinker and polymath Gregory Bateson, as uncommitted potentiality for change. There are more than 4,000 strains of potato in the Andes, but only a minuscule proportion of the total number of varieties is grown on a large scale. As The Anthropology of Sustainability (2017) puts it, of 350,000 globally identified plant species, 7,000 have been used by humans as food. In the Anthropocene today, 75 per cent of the food eaten by human beings is composed of just 12 crops and five animal species. Should one or two of them fail, the outcome may well be crisis or famine. Had we instead distributed investment more broadly and evenly, the risk would be less. A peasant who grows a bit of maize, some legumes and some tubers has more options than one who has shifted to dependence on a single cash crop.

Genetic diversity in many food crops has been reduced deliberately for the sake of increased productivity. The logic of the plantation is economically profitable and can be a blessing for the poor, at least in the short term, but it has ecological side-effects, known and unknown, as well as reducing the range of options for the future. Regarding culture and language, one may well claim that, if everybody learns English, we can all communicate with each other, but there will also be a number of things that will forever remain unsaid. Language is being platformised like the ecosystem of the monocrop plantation. The linguistic equivalents of the rainforest ecosystem are forced into oblivion when language evolves along the same lines as the plantation.

This is the point where biosemiotics can illuminate some fundamental, and disconcerting, aspects of the contemporary world. The pioneering biosemiotician Jesper Hoffmeyer (1942-2019) fashioned some useful concepts. He was inspired by the philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce, a founder of semiotics, as well as by Bateson. Hoffmeyer had a degree in biochemistry, worked as a biologist at the University of Copenhagen, and collaborated with philosophers, literary scholars and social scientists. His first book in English, Signs of Meaning in the Universe (1996), explains biosemiotics as a scientific approach to living systems that interprets relations in nature as systems of signs. The method is the same as that employed by the Italian author and semiotician Umberto Eco in his celebrated essay ‘Lumbar Thought’ (1986), about blue jeans as a semiotic powerhouse brimming with signs, some directed at the surroundings, some communicating – unpleasantly – with his body parts. After reading Eco, it is impossible to see a pair of jeans as a mere item of clothing. And having read Hoffmeyer, you can no longer look at an ordinary shrub without being alert to the insects, the undergrowth and the structure of its twigs and leaves.

A plant could stretch towards the sun or direct its roots to the most nutritious soil

Biosemiotics does not reject Darwinian evolutionism, but studies communication and connections rather than competition and struggle. When a fox becomes aware of a hare in the vicinity, its reaction and eventual attack forms part of a semiotic chain that also includes the flight of the hare and cues given by the physical environment, such as hiding places. Hoffmeyer uses the term ‘semiotic scaffolding’ to show how the surroundings provide incentives and constraints to the communicating creature. In the same way as intellectual input from unexpected quarters give us the possibility to think differently, an organism – be it a slug or a chimpanzee – may flourish or wither depending on the options provided by its surroundings.

In one of his most authoritative statements, Hoffmeyer said: ‘Semiotic freedom may in fact be singled out as the only parameter that beyond any doubt has exhibited an increasing tendency throughout the evolutionary process.’ What did he mean by that?

Every organism has a certain degree of semiotic freedom, meaning the ability to do something differently. A plant could stretch towards the sunlight or direct its roots to the most nutritious and well-watered soil, or it could respond differently to signs in its surroundings. A dog can play with its owner and pretend to bite her; in other words, it is capable of meta-communication by placing its actions in scare quotes, as it were, signalling: Hey, look, this is play, I’m only joking. The relationship between humans and dogs releases greater semiotic freedom – more alternatives, more flexibility, more depth or nuance in meaning – than the relationship between a pine tree and the blueberry bushes growing beneath it, although an exchange of signs takes place in the latter case as well. Hoffmeyer thus describes an evolutionary process towards ever greater complexity: more communication, more relationships, a denser forest of signs communicating ever more content at several logical levels. This development is an outcome of specialisation, which in turn is a result of the need to find vacant niches in ecosystems that are becoming increasingly crowded. In the realm of culture, the enormous variation in language, customs, technologies, cosmology and kinship that can still be witnessed today is the outcome of a process of gradual cultural differentiation that began soon after the emergence of modern humans about 200,000 years ago.

Biosemiotics makes it possible to erase the conventional distinctions between mind and matter, humans and nonhumans, and the conscious and the non-conscious, which have characterised Western thought for centuries. What matters is what takes place between entities, not within them. It is possible to study any form of life, from the mycorrhizal networks connecting fungi and plants, to a philosophical treatise, using the same toolbox. This is not an option to be ignored at this historical juncture, when Anthropocene effects are transforming life on the planet, human and nonhuman alike, at an astonishing speed.

The urgent question concerns whether the process towards greater overall semiotic freedom continues, or if the homogenising forces of globalisation currently lead to its reduction. Let us consider a few examples that seem to indicate a dramatic loss of diversity and semiotic freedom.

Doing anthropological fieldwork in central Queensland some years ago, I took part in a popular early evening activity that recruited families, retirees and other engaged citizens. It is known locally as toad busting, and its online ads are accompanied by a cheerful ditty adapted from the movie Ghostbusters. In the decades following the introduction of the cane toad (Rhinella marina) to the state in the 1930s, this toad has spread so quickly, and with such dire ecological consequences, that volunteers and NGOs mobilise weekly to collect the toads, which are subsequently killed by freezing. The toads are sluggish, but slimy and endowed with poison glands. Participants are equipped with a pair of gloves and a sack. Regardless of the dexterity and perseverance of the toad-busters, the activity is comparable to urinating on a desiccated gum tree. It contributes next to nothing to modifying the impact of the cane toad on the ecosystem, but at least it provides the activists with the feeling that they are chipping in to salvage the unique, fragile Queensland ecology.

Cane toad. Photo GG Alice/Flickr

The cane toad is large and fast-reproducing, and it is more resistant to drought than other amphibians. It was brought to Australia from Hawaii, whence it was imported from Central America, and assigned the task of controlling a dastardly beetle with a taste for sugar cane (also an imported species). The toad never warmed to the sugar plantations and began to move on almost immediately, displacing other species and contributing to ecological destabilisation. Owing to its poison glands, predators that eat it usually die. The toad spreads westwards at a speed of about 40 kilometres (25 miles) a year. About a decade ago, it crossed the border to Western Australia, though it is still associated with Queensland. Ahead of the annual State of Origin rugby tournament, some Queenslanders once spoke of the New South Wales team as ‘cockroaches’, and their southern neighbours immediately retaliated by nicknaming the Queenslanders ‘cane toads’.

Nobody seriously suggests the removal of sheep from New Zealand or grapevines from the Western Cape

How does this relate to biosemiotics? The spread of the poisonous cane toad reduces the flexibility, diversity and options available to the ecosystem. When other species are decimated, the system is semiotically impoverished since the information flowing through it is reduced and becomes less diverse. The loss of semiotic freedom is obvious.

Australia is a veritable treasure trove of stories about the ways in which introduced species may create imbalances in ecosystems and contribute to a reduction of species semiotic freedom, from rabbits and foxes, introduced in the 19th century, to flowery shrubs, feral pigs and camels wreaking havoc today. Although introduced species deservedly get a lot of bad press, keep in mind that they are often beneficial, not only for humans, but also for other species and for biodiversity. The introduction of new species often increases diversity and semiotic freedom at the level of the ecosystem. So-called invasive species are, in other words, often harmless and indeed beneficial to diversity. Nobody seriously suggests the removal of sheep from New Zealand or grapevines from the Western Cape, and anyone proposing to eradicate the corn fields of East Africa and asphyxiate the lapdogs of New York would be met with a tired shrug. In my native Norway, the king crab, an initially despised invader from Russian waters, eventually has become a delicacy, and the invasive humpback salmon is currently on its way to the restaurants of the country. It may be tempting to conclude that ecosystems have always been dynamic, and that they have no pristine, ‘original’ state of endemic splendour.

Destabilisation nonetheless has its cost, and both the crab and the salmon threaten endemic species. New species affect relationships throughout the ecosystem, whether they are introduced deliberately or arrive with ballast water or in the suitcase of a tourist. As a general rule, free competition means that fewer are left on the playing field when the dust has settled. Whether or not humans lose or benefit from them in the short term, introduced species often result in a reduction in diversity, in a manner resembling the mechanisms at play in laissez-faire economics. Gaining popularity around the same time as Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution in the latter half of the 19th century, this school of economic theory preaches that it is natural and healthy that the small and weak should perish since they lack competitiveness. Not everyone agrees with this view since it reduces diversity in the economy by bolstering large corporations and, similarly, monocultures in agriculture reduce the overall semiotic freedom of the ecosystem through a reduction in flexibility.

Species have migrated since the beginning of life on the planet, and cultures have changed and influenced each other since we started to create abstract concepts many thousand years ago. The discipline of biogeography amounts to the study of species distribution and mobility, with a special interest in climate zones, islands and barriers such as mountain chains and open seas. On oceanic islands and the isolated continent of Australia, evolution could take unique paths. The giant tortoises of the Galápagos islands, the Mauritian dodo and the Komodo lizard, which would be unable to thrive on a continent with voracious predators, could survive for millions of years on islands, owing to limited competition. Such islands can be compared, by analogy, to countries that protect local produce and handicrafts through tariffs and legislation against imported goods. In both cases, impediments to free flow enhance diversity and increase the number of available options.

The temporal scale of cultural history is much shorter than that of evolution, but there is a pattern resemblance, and the proliferation of cultures since we became anatomically modern about 200,000 years ago is astonishing – as are the forces now threatening to reduce much of this diversity, thereby reducing semiotic freedom and limiting our options as a species.

In dense forests, barren semideserts and narrow mountain valleys, unique cultural forms evolved and could thrive thanks to limited contact with the outside world. In New Guinea, a large, mountainous and forested island, horticulture has probably been practised since the beginning of cereal cultivation in the Fertile Crescent. When Europeans began to explore the New Guinea highlands less than a century ago, it appeared to them as though time had stood still for thousands of years. Headhunting was still widespread, metals were unknown, and several hundred languages were spoken, none of them written. Moreover, many of these languages appeared to be unrelated to all other languages, including those spoken in the next valley. Along the northern coast of the island, where there had long been regular contact with traders, pirates, castaways and missionaries, the situation was different. Many coastal New Guineans speak Austronesian languages belonging to a family stretching from Madagascar in the west to Rapa Nui in the east. The ocean has always been a road, both biologically and culturally, with islands and ports as its busy crossroads.

This road was paved and expanded to a highway in the centuries following the European conquests starting with Christopher Columbus in 1492. The process described by the historian Alfred Crosby in his book The Columbian Exchange (1972) encompassed plants, animals and humans. The slow migration of hungry herds, the natural rafts of straw and driftwood, and the droppings of migratory birds were no longer necessary for animals and plants to spread worldwide. At the same time, human migrations became intercontinental through settler colonialism and transatlantic slavery. States and empires emerged not just in parts of the world but across the planet, and they increasingly resembled each other. Until quite recently, the dissemination of plants and animals worldwide was rarely perceived as a problem. Botanical gardens, many of which are located to the tropics, were established as deliberate attempts to accelerate the introduction of new plants, not least for the benefit of local farmers.

Rather than organising diversity, the plantation replicates homogeneity

This would change, as the detrimental effects of ecological imperialism became increasingly visible. In the past few decades, it is as though the speed limits on the global highway have been abolished. Changes now take place so fast that researchers and even journalists find it difficult to keep up the pace. In my own work, I have proposed the term ‘overheating’ to describe the increased rhythm of change since around 1991. In their book The Great Acceleration (2016), John McNeill and Peter Engelke describe what’s happened since the Second World War, but it would also make sense to talk about an acceleration of acceleration since the end of the Cold War around 1990. During the past three decades, world trade has tripled, tourism has quadrupled, and the amount of plastic in the ocean has grown by a factor of five. Environmental destruction has exploded along with a massive growth in consumption and mobility, with anthropogenic climate change as the paradoxical crowning achievement of the present era. The availability of abundant and powerful energy thanks to fossil fuels, a blessing for humanity since the early 19th century, has now become its damnation and our self-inflicted recipe for catastrophe. The dependence on these energy sources have greatly reduced flexibility, limiting the number of options to do things differently.

In his book 1493 (2011), the science journalist Charles Mann proposed supplementing the concept of the Anthropocene with that of the ‘Homogenocene’. His book, inspired by Crosby’s The Columbian Exchange, deals with the cumulative effects of European conquests, with a special emphasis on food production. Mann is concerned with the reduction of biological diversity as a result of global exchange and growth, and the Homogenocene is an era when the logic of the plantation and the factory predominate. When a palm oil plantation replaces a rainforest, not only do a great variety of trees disappear, but so do the micro-organisms, insects, the birds who used to feed on the insects, the seeming chaos of flowers, ferns, fungi and other organisms relying on the trees and each other. The soil itself is transformed, and the entire biotope is simplified and standardised. Rather than organising diversity, the plantation replicates homogeneity.

The plantation and the large, monocultural field of a foodcrop – think corn in the Midwest – is productive, but semiotically poor. Each square foot ‘says’ the same thing, unlike in a forest, where no two trees of the same species are standing next to each other. In a study of consumption, the same point about homogeneity, standardisation and replication of similarity was made by the sociologist George Ritzer in The McDonaldization of Society (1993). Ritzer depicts a world of production and consumption where upscaling, standardisation and simplification predominate. Chains and identical franchise outlets outcompete quirky family businesses, and the principle of the economy of scale applies everywhere because it generates the largest profits. We may think about icons of the current era such as the plantation, the container ship, the smartphone and the spread of large languages at the expense of small ones, along exactly the same lines. In all cases, more communication takes place quantitatively speaking, but it is semiotically poorer because everybody is increasingly saying the same thing.

It is more difficult to gauge diversity in culture than in ecosystems. Consumer researchers have often pointed out that consumers are creative and independent, and that apparent standardisation may conceal considerable variation. This is not an irrelevant objection, but it is difficult to deny that the new diversity is qualitatively different from the old. Language death may be an indicator. In the early 2020s, we have about 7,000 languages spoken worldwide. Linguists estimate that 90 per cent of them may be gone in just a few decades. If there is some truth to the assumption that every language produces a unique vision of the world (‘certain ideas can be expressed only in German’, as I was once taught), there is a case for suggesting that the cultural diversity of the world is facing a mass extinction on a par with the reduced complexity of the global biosphere. The world is becoming semiotically poorer. With every extinct language, a unique way of perceiving the world disappears.

But isn’t the early 21st century an era when new cultural forms are continuously created owing to intensified intercultural encounters, migration and globalisation? The concept of ‘super-diversity’ was introduced by the anthropologist Steven Vertovec to describe precisely that ‘diversification of diversity’ that can now be observed, especially in the cultural crossroads of major cities. It is true that new cultural identities are continuously being fashioned, and that neither ethnicity, religion nor gender are fixed and immutable, but they all seem to be of the same kind. As loyal individualists and consumers, they – we – choose among the alternatives on offer in the supermarket of identity. People may do their best to be unique and different, but they do so within a global grammar for the expression of uniqueness. Everybody tries to be unique in the same ways, conforming to a shared language that makes cultural differences comparable.

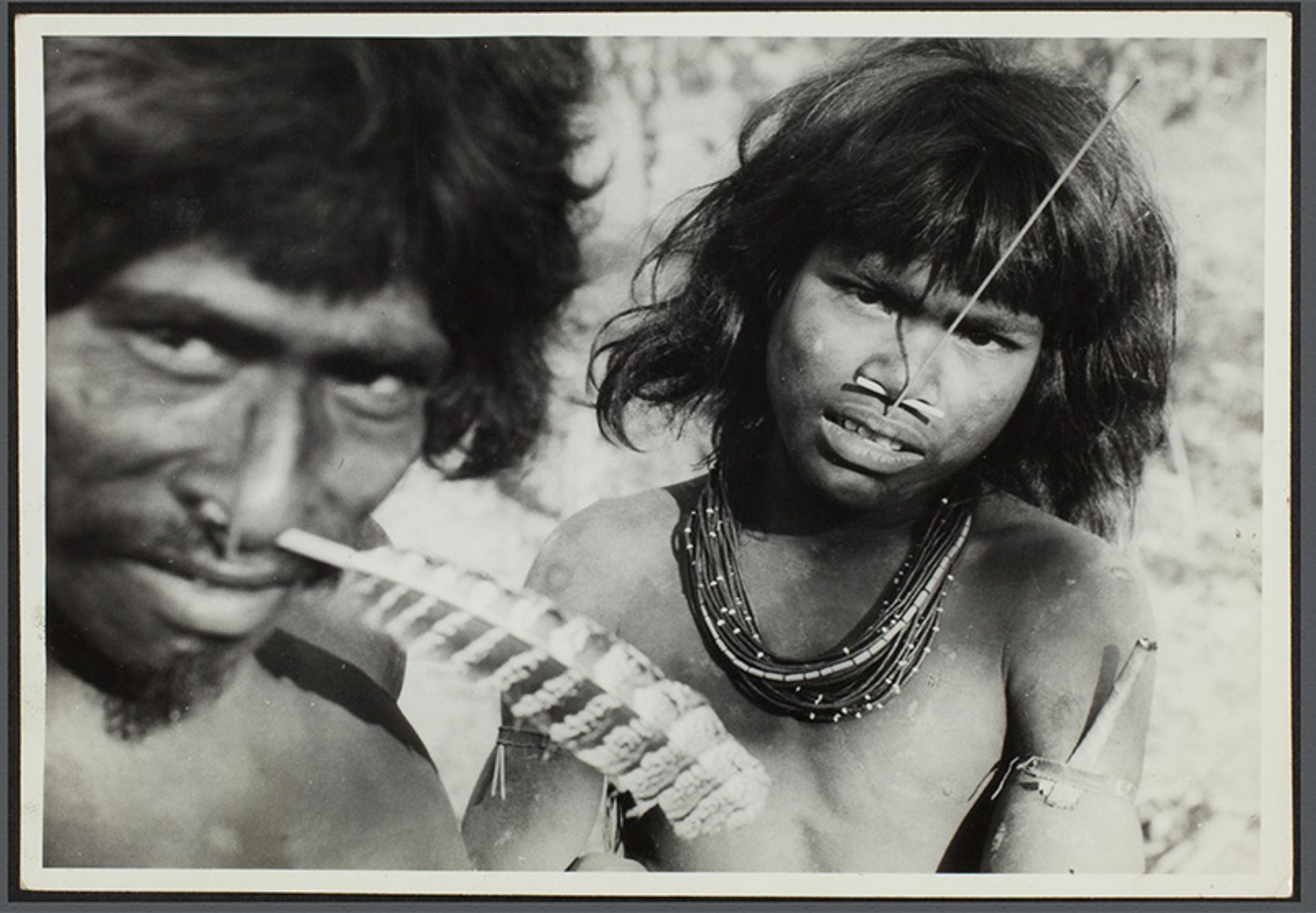

Two men of the Bororo tribe in Brazil. Photo c1938 by Claude Levi-Strauss. Courtesy Musée de Quai Branly, Paris

Before the global hegemony of the Homogenocene, different peoples could be quite incomprehensible to each other. In the celebrated travelogue Tristes Tropiques (1955), the anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss describes an encounter with Indigenous people in Brazil in the 1930s as though there were a glass wall separating them. They could see each other, but mutual understanding seemed impossible. This kind of alienness has now been whittled down by the mighty grinding machine of modernity. As the anthropologist Clifford Geertz once said, in a wry comment on the flattening of cultural differences, cultural diversity would surely continue to exist – the French would never eat salted butter, he asserts, before adding: ‘But the good old days of widow burning and cannibalism are gone forever.’

As songbirds vanish, so does traditional knowledge

UNESCO did not see this distinction when they produced the report Our Creative Diversity in 1995. The authors celebrated cultural diversity while at the same time promoting a global ethics. Everybody should be encouraged to be different and unique, but only in so far as they followed established rules. They had to become similar in order for their uniqueness to be legitimate. Handicrafts, yes. Headhunting, no.

In a manner resembling the new cultural diversity, biological diversity is being safeguarded in national parks, zoos and seed banks but, outside the enclosures, the tendency is unequivocal. The loss of variation is indisputable both as regards culture and biology. Semiotic freedom is reduced when the available options become fewer, and the long-term effects are potentially catastrophic because we are losing the flexibility we will need to solve the challenges raised in the Anthropocene, notably those of climate change and environmental destruction.

‘Over increasingly large areas of the United States, spring now comes unheralded by the return of the birds, and the early mornings are strangely silent where once they were filled with the beauty of bird song.’ The quote is from Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962), a book that marked the beginning of the contemporary environmental movement. And, as songbirds vanish, so does traditional knowledge. The Malian intellectual Amadou Hampâté Bâ has said that when an African elder dies, it is as if a library is burnt down.

Considering the effects of globalisation towards homogenisation, simplification and standardisation, it is now possible to propose that the evolutionary trajectory towards greater semiotic freedom has been reversed. In his account of increasing semiotic freedom, Hoffmeyer did not mention the five earlier mass extinctions in evolutionary history, which led to a temporary reduction in semiotic freedom, but his argument is nevertheless an important one. As I have argued, it can also be applied to the cultural history of humanity. Since the origin of Homo sapiens in Africa around 300,000 years ago, groups have branched off, diversified, adapted to and developed viable niches in all biotopes except Antarctica. Thousands of mutually unintelligible languages, unique religions and customs, kinship systems, cosmologies and economic practices produced a world of a fast-growing number of differences. Now, as a result of frantic human activity across the planet, there is a dramatic reduction in semiotic freedom, a loss of flexibility and options. This would imply a dramatic shift, and we may already have passed a tipping point.

A major challenge today consists in finding ways of halting this movement away from a world of many differences towards a world of just a few, and defences of biodiversity and cultural diversity are two sides of the same coin. Until now, critics of the negative effects of globalisation have typically focused on inequality, climate change and environmental damage, or the marginalisation of vulnerable groups such as migrants, refugees and Indigenous peoples. It is time now to view the global situation through a lens enabling us to see all the destructive effects of globalisation as threads in the same tapestry. Contemporary globalisation is a bulldozer on speed, razing rainforests, turning tribal peoples into urban slumdwellers, simplifying ecosystems and obliterating traditional livelihoods. The loss of semiotic freedom is creating a poorer world of reduced beauty but, more seriously, it leads to ecological disaster and diminishing options for humanity. A sensible slogan for the remainder of this century could be TAMA: there are many alternatives. These alternatives, from rainforests to small languages, from traditional agricultural practices to island ecosystems, urgently need our protection or support.