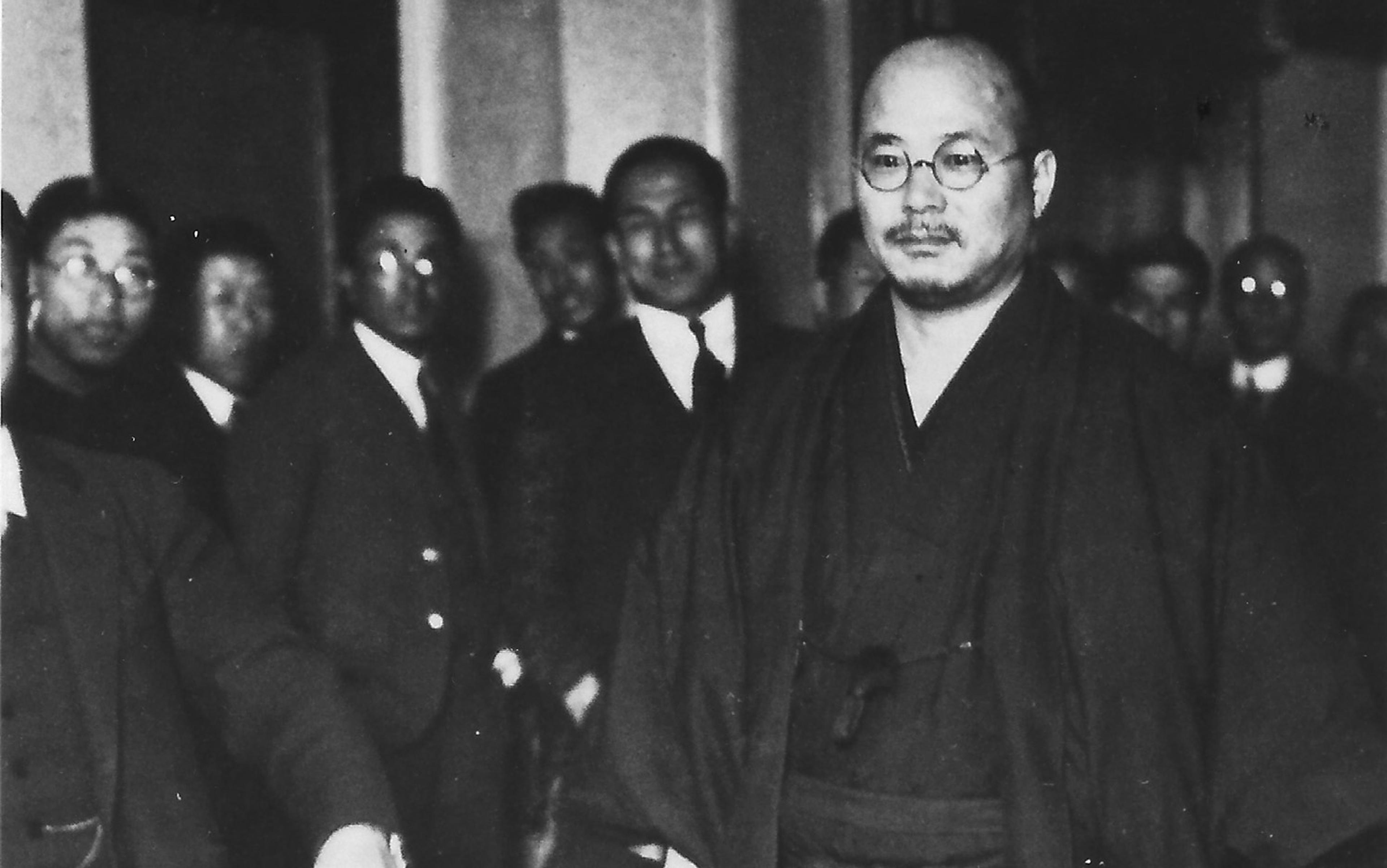

On an early winter’s morning in 1945, four months after the end of the Second World War, a shabbily dressed man in his late 50s walked into the General Headquarters (GHQ) of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers in Tokyo. His name was Nissho Inoue, a convicted domestic terrorist and lay disciple of one of Japan’s most famous modern Zen masters, Gempo Yamamoto, abbot of both Ryutaku-ji and Shoin-ji temples.

Inoue had been instructed to report for questioning as a war-criminal suspect because he had once been the leader of a terrorist band, popularly known as the ‘Blood Oath Corps’. His civilian band members were initially responsible for the deaths of two of Japan’s political and financial leaders in the spring of 1932, with plans to assassinate many more. A second group of military band members assassinated the prime minister Tsuyoshi Inukai on 15 May 1932.

Once inside the GHQ, Inoue was led to the office of Lt Parsons, the British officer who was to interrogate him. Lt Parsons began his interrogation:

Mr Inoue, I didn’t request your appearance today in order to find out what you did before and during the war. We already know what you did. We know you were not only an ultra-Right-wing nationalist but the leader of a band of terrorists as well. In fact, it is a matter of common knowledge the world over that it was you who started the Second World War. There’s no point denying it. It’s therefore unnecessary for me to enquire about any of this.

Inoue denied the allegations. Historically however, it is true that the terror resulting from the assassinations he led brought an end to Japanese democracy: ie, an end to the popularly elected, party-based, parliamentary government that had come into existence during the reign of Emperor Taisho (1912-26). Henceforth, from 1932 through to the end of the Second World War, the emperor and his advisors would appoint prime ministers. This consolidation of imperial power in turn made possible the Japanese military’s invasion of China in July 1937, eventually leading to the attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941. Thus, Lt Parsons’s charges were not as farfetched as they might appear at first.

What had motivated Inoue and his band to undertake their terrorist acts? After all, neither Zen nor Buddhism is known for its involvement in terrorism.

Following his father’s death in 1926, Emperor Hirohito had ascended the throne at a time of great social and political domestic instability. Across Japan, banks were closing, and the government was arresting Left-wing activists, accusing them of harbouring ‘dangerous thoughts’ as defined by the Peace Preservation Law.

The Great Depression that began in the United States in 1929 greatly reduced both demand and prices for raw silk, Japan’s single largest export product. At the same time, Japan’s population was increasing by nearly 1 million people a year. Its workforce was growing at an annual rate of approximately 450,000 people, all seeking jobs in a shrinking economy.

Hungry Children in Iwate prefecture in northern Japan in November 1934. They are eating raw white radishes (daikon) to assuage their hunger. Photo courtesy the author.

In addition, successive poor harvests in the early 1930s, especially in the northern prefectures, brought widespread starvation to many parts of the country. Rural debt rose rapidly, leading to delinquent tax payments, and more and more farmers either lost their land altogether or were forced to take desperate measures, such as selling their daughters into prostitution. Japanese society was in a state of crisis that in many people’s eyes required immediate and drastic remedies.

Inoue, who had begun his Zen training in Manchuria, responded to this crisis by accepting an invitation to head a newly built Buddhist temple. It was 1928 and the new temple was in the village of Oarai, near the city of Mito north of Tokyo. Inoue threw himself into the work of training a small group of about 20 young people. He drew on a variety of Zen training methods, including meditation practice; assigning koans (Zen riddles) and conducting private interviews with his disciples, all to create an intrepid group of volunteers with a ‘do or die’ spirit.

At first, Inoue planned to train young people for legal political activism. However, by 1930, under the pressure of events and young civilian and military activists, Inoue decided to take more resolute measures. ‘In an emergency situation,’ he wrote, ‘emergency measures are necessary. What is essential is to restore life to the nation. Discussions over the methods for doing this can come later, much later.’ Inoue fully expected that his political actions would lead to his death: ‘We had taken it upon ourselves to engage in destruction, aware that we would perish in the process.’

In his previous Zen training, Inoue found the basis for his commitment to destruction. Drawing on the lessons of a 13th-century Zen collection of koans known as the Mumonkan, or ‘The Gateless Barrier’, he claimed:

Revolution employs compassion on behalf of the society of the nation. Therefore those who wish to participate in revolution must have a mind of great compassion toward the society of the nation. In light of this there must be no thought of reward for participating in revolution.

In other words, in the violently destructive acts of revolution one would find the mind of Buddhist compassion.

He and his band members were prepared to die in the process of the revolution

In October 1930, Inoue and his band shifted their base of operations to Tokyo. From there, he recruited more young people, including some from Japan’s most prestigious universities. One of Inoue’s band members later explained: ‘We sought to extinguish Self itself.’

Inoue’s band chose assassination as their method of revolution. Assassination, Inoue explained, ‘required, whether successful or not, the least number of victims’. He also thought it ‘was best for the country, untainted by the least self-interest’. He and his band members were prepared to die in the process of the revolution. By being prepared to sacrifice themselves, they believed they could ensure that as few people as possible would fall victim to revolutionary violence.

They intended to assassinate some 20 Japanese political and financial leaders but managed to kill only two before the remaining band members, Inoue included, were arrested. Junnosuke Inoue (1869-1932), a former finance minister, was their first victim, shot on the evening of 9 February 1932 as he entered Komamoto Elementary School in Tokyo to deliver an election speech. His assassin was 20-year-old Sho Onuma (1911-1978), a onetime baker’s assistant and carpenter’s apprentice.

On the morning of the assassination, Onuma was uncertain whether he would be able to carry out his assignment. Seeking strength from his Buddhist training, Onuma recited four sections of the Lotus Sutra to calm himself. Thereafter, he started to practice Zen meditation: ‘When I opened my eyes from their half-closed meditative position, I noticed the smoke from the incense curling up and touching the ceiling. At this point it suddenly came to me – I would be able to carry out [the assassination] that night.’

Baron Takuma Dan (1858-1932), the managing director of the Mitsui holding company and a financial magnate, was their second victim, shot as his car pulled up to the side entrance of the Mitsui Bank Building. The assassin was 21-year-old Goro Hishinuma. Six days after Dan’s death, and realising that his arrest was imminent, Inoue surrendered to the police.

The trial of Inoue and his band began on 28 June 1933. At the third hearing, Inoue’s chief lawyer initiated a process that ultimately resulted in the presiding judge stepping down from the case due to such inappropriate actions as ‘yawning’ and ‘looking around’ during deliberations. The trial did not resume until 27 March 1934 under a new chief judge who gave the 14 defendants, including Inoue, the right to not only wear formal kimono (instead of prison garb) in the courtroom but to expound at length on the ‘patriotic’ motivation for their acts.

In his court testimony, Inoue made it clear that his Buddhist faith lay at the heart of his actions: ‘I was primarily guided by Buddhist thought in what I did. That is to say, I believe the teachings of the Mahayana tradition of Buddhism as they presently exist in Japan are wonderful.’

With regard to Zen, Inoue said: ‘I reached where I am today thanks to Zen. Zen dislikes talking theory so I can’t put it into words, but it is true nonetheless.’ Inoue went on to describe an especially Zen-like manner of thinking when he was asked about the particular political ideology that had informed his actions. He replied: ‘It is more correct to say that I have no systematised ideas. I transcend reason and act completely upon intuition.’

The Zen influence on Inoue’s statement is clear. Here, for example, is what D T Suzuki had to say in Zen and Japanese Culture (1938):

Zen upholds intuition against intellection, for intuition is the more direct way of reaching the Truth. Therefore, morally and philosophically, there is in Zen a great deal of attraction for the military classes … This is probably one of the main reasons for the close relationship between Zen and the samurai.

Inoue testified that Buddhism taught the existence of ‘Buddha nature’. Although Buddha nature is universally present, he argued, it is concealed by passions, producing ignorance, attachment and degradation. He saw the Japanese nation as being similar. Its nature was truly magnificent, identical with the ‘absolute nature of the universe itself’. However, human passions for money and power and other fleeting things had corrupted the polity.

At this point, the judge interrupted to ask: ‘In the final analysis, what you are saying is that the national polity of Japan, as an expression of universal truth, has been clouded over?’

Inoue replied: ‘That’s right. It is due to various passions that our national polity has been clouded over. It is we who have taken it on ourselves to disperse these clouds.’

Inoue meant that in killing (and planning to kill), he and his band were restoring the brilliance and purity of the Japanese nation. Their victims had been mere obscuring ‘clouds’.

‘There is, apart from those who are selfish and evil, no fair and upright person who would criticise the accused’

The morning edition of The Asahi Shimbun newspaper on 15 September 1934 carried the news: ‘Zen Master Gempo Yamamoto, spiritual father of Nissho Inoue, arrives in Tokyo to testify in court. Yamamoto claims: “I’m the only one who understands Inoue’s state of mind.”’

Yamamoto testified that ‘in light of the events that have befallen our nation of late, there is, apart from those who are selfish and evil, no fair and upright person who would criticise the accused for their actions’. Why? Because Yamamoto claimed that their actions were ‘one with the national spirit’. But what about the Buddhist prohibition against taking life? Yamamoto explained:

It is true that if, motivated by an evil mind, someone should kill so much as a single ant, as many as 136 hells await that person … Yet, the Buddha, being absolute, has stated that when there are those who destroy social harmony and injure the polity of the state, then even if they are called good men killing them is not a crime.

While there is no question that Buddhism promotes ‘social harmony’ between both individuals and groups, support for killing ‘those who destroy social harmony and injure the polity of the state’ is not to be found in Buddhist sutras. Instead, the source of these ideas is found in neo-Confucianism, whose social ethics emphasise the importance of social harmony achieved through a reciprocal relationship of justice between superiors, who are urged to be benevolent, and subordinates, who are required to be obedient and loyal.

Japanese Zen accepted and taught neo-Confucianism in Japan from the 1400s onwards even while continuing to pay lip-service to Buddhism’s traditional precepts. In pre-war Japan, the state was headed by an allegedly divine emperor whose benevolence extended to the wellbeing of all Asian peoples, especially those colonised by Western nations or endangered by the spread of communism. It was the emperor to whom the Japanese people were taught they owed absolute obedience and loyalty. Believing this, Yamamoto ended his testimony by stating:

Inoue’s hope is not only for the victory of Imperial Japan, but he also recognises that the wellbeing of all the coloured races (ie, their life, death or possible enslavement) is dependent on the Spirit of Japan. There is, I am confident, no one who does not recognise this truth.

In the eyes of one of Japan’s most highly respected Rinzai Zen sect masters, who conflated Buddhist and neo-Confucianist ethics, Inoue and his band’s terrorist acts were by no means ‘unBuddhist’ or blameworthy. And despite his court testimony defending terrorists, Yamamoto was so highly respected by his fellow Zen masters that they chose him to head the entire Rinzai Zen sect in the years following Japan’s defeat in August 1945. As for Inoue, master and disciple remained close until the former’s death in 1961.

Inoue and his band members were all found guilty. On 22 November 1934, he and the two assassins were given life sentences, while the other band members received sentences ranging from 15 to as few as three years.

By Japanese standards, the sentences were lenient. In addition, in early 1935, 11 of the accused were amnestied and released from prison. Inoue’s sentence was shortened until in 1940 he, too, was released from prison. In a most unusual step, Inoue’s guilty verdict was completely erased from the judicial record. It was as if he had never been involved in terrorism at all.

In another surprising development, shortly after his release from prison, the prime minister Prince Fumimaro Konoe (1891-1945) invited Inoue to become his advisor, providing him with living quarters on his estate. That is to say, a former leader of a band of terrorists had exchanged his prison cell for life on a prime minister’s estate. Clearly, Inoue had the support of some of Japan’s most important political leaders.

Moreover, Inoue never admitted to any kind of remorse for having ordered the assassination of some 20 Japanese political and financial leaders, of whom two were killed initially and one, the prime minister Inukai, killed shortly thereafter. In fact, Inoue later wrote describing his actions as having ‘dealt a blow to the transgressors of the Buddha’s teachings’.

Religious terrorism, of course, remains a current reality. The question can be asked, are there any lessons for the present to be learned from the Zen-affiliated terrorism described here?

First, Inoue’s story reminds us that terrorism is a tactic employed by the weak against the strong for the simple reason that terrorists lack the means to employ any other method. Initially, Inoue had no intention of engaging in terrorist acts. But he reached the conclusion that social reform couldn’t wait, and embraced terrorism as the only tactic left open to him. To believe, as many governments claim, that it is possible to ‘stamp out’ or ‘eradicate’ terrorism by killing all terrorists, or suspected terrorists, is akin to believing, in the case of an air force, that aerial bombardment as a tactic of warfare could be permanently eliminated if every living bombardier (or drone operator) were killed.

Second, terrorism is not simply an isolated product of crazed or fanatical religious adherents. Instead, there are nearly always underlying political, economic and social causes. Japan in the 1930s was a socially and economically unjust society. Corrupt economic and political leaders showed little concern for the welfare of the majority of the Japanese people. The economic disparity between rich and poor led to attempts, increasingly violent, to enact social reform. To many Japanese frustrated with ineffective peaceful and legal efforts, terror seemed to be the only remaining avenue available to enact change.

Third, terrorists do not view themselves as hate-filled, bloodthirsty monsters. Instead, as incongruous as it might seem, many are motivated, like Inoue, by nothing less than ‘compassion’ or a deep concern for their compatriots. ‘Kill one in order that many may live’ is how Inoue and his band put it. They believed compassion and concern for the wellbeing of the majority of the exploited and oppressed in Japan, especially the rural poor, justified their violent actions. It couldn’t be helped if a few had to die for the majority to flourish.

No matter how inhumane their acts, they are moral in their own eyes by virtue of their concern for others

Finally, it is important to recognise that religion-related terrorists care so much about protecting or rescuing those in perceived need that they are willing to sacrifice their own lives in the process of carrying out their terrorist acts. Inoue and his band regarded themselves as no more than ‘sacrificial stones’ (pawns) in the struggle to reform Japan. This conviction allowed them to view themselves as Buddhist Bodhisattvas, figures ever-ready to sacrifice their own welfare for the sake of others. Such self-sacrifice resonates with the tenets of many religious faiths, and helps terrorists to see themselves as not only ethical but even unselfish exemplars of their faith.

Temple where Nissho Inoue and his terrorist trained as it appears today. It’s full title is “Rissho Gokokudo” (Temple to Protect the Nation [by] Establishing the True [Dharma]). Photo courtesy the author.

It’s this view of themselves as ‘good’ and ‘self-sacrificial’ that allows many terrorists to commit their heinous acts, secure in the mistaken belief that they are acting ethically and according to the highest dictates of their faith. Thus, to demonise terrorists, turning them into evil incarnate, is to fail to recognise their most salient characteristic. No matter how twisted and inhumane their acts are, they are nonetheless moral in their own eyes by virtue of their concern for others, their willingness to sacrifice themselves on their (or God’s) behalf. Thus, depending on the context, religious-affiliated terrorists regard themselves as ‘freedom fighters’, ‘heroes of the faith’ or, more typically, ‘martyrs’.

One common sentiment throughout the world – at least in non-Islamic countries – is that Islam, or at least some aspects of ‘Islamic fundamentalism’, is primarily if not solely responsible for religion-related terrorist acts. The proffered ‘solution’ (or demand) is that Muslims change their terror-prone religion into a religion of peace by abandoning such doctrines as jihad. The unstated assumption is, of course, that the world’s other major religions lack such violence-affirming doctrines and are completely peaceful. However, as Inoue and his band reveal, Buddhism, especially in its Zen formulation, is quite capable of providing the justification to kill even those whom Zen Master Gempo Yamamoto referred to as ‘good men’.

Historically speaking, no religion is free from having been invoked or contributing to terrorist acts or providing the supposed justification for terrorism. Among religions, today’s ‘Islamic terror’ is no more than the ‘flavour of the day’ or the immediate problem. This is certainly not to deny that Islam-related terror is a deadly serious issue, but it is also a Buddhist, a Christian, a Jewish and a Hindu issue. Simply placing the blame on Islam blocks a solution since it prevents mutual understanding and leads to an unfounded, self-righteous attitude on the part of adherents of non-Islamic faiths. It also raises the thorny question of why it is considered bad to kill people in the name of a religion, for example Islam, yet acceptable, even praiseworthy, to kill them in the name of the state.

In seeking to understand acts of terrorism, the question ‘Who benefits?’ must always be asked. The historical record reveals that even governments, or at least parts of governments, are willing to support terrorist acts if this advances what they regard as their national interest. It’s not unusual for powerful, behind-the-scenes actors, including governments, to serve as ‘enablers’ of terrorism through funding, supply of weapons, training, suggested targets, etc.

The true solution to terror is one that is seldom discussed, and even less often acted upon. Namely, the solution to all but ‘lone-wolf’ acts of terror is the establishment of socially and economically just societies, no matter how difficult that might be. Where oppression exists, resistance is inevitable. Religion is one of the most available means of organising resistance, for it provides an emotionally powerful and compelling way to speak and think about sacrifice and justice. But it is critically important to remember that state and secular forces in society seek to maintain, or even enhance, their own power by secretly funding and supporting terrorists, capitalising on the religious fervour of believers, especially the latter’s willingness to sacrifice themselves. Terrorism, at least on a large scale, could not exist without their support.

At the same time, those who believe in the salvific power of religion must acknowledge how easily their religion’s highest ideals can be, and have been, hijacked by those seeking to enhance their worldly power. In the absence of critical self-reflection on the part of all religious adherents, the cycle of religion-affiliated terrorism will never be broken. In the words attributed to the 17th-century French scientist Blaise Pascal: ‘Men never do evil so completely and cheerfully as when they do it from religious conviction.’ If nothing else, this is the lasting legacy, and lasting warning, that Inoue and his band of Zen terrorists have left us.