Deep in the south of Egypt, on the west bank of the Nile facing the historic capital Thebes, stand two 60-foot-tall statues of the pharaoh Amenhotep III (14th century BCE). By the time the Romans annexed Egypt in 30 BCE, these colossi were an ancient remnant of the grandeur of the pharaoh’s mortuary temple, doomed by the Nile’s floodwaters, that they had once fronted. It was not just the visual impact of the lonely, poignant pair that captivated visitors, but also the extraordinary whistling sounds that emanated from the northern statue at dawn, likely the result of earthquake damage in 26 BCE.

But Greek and Roman tourists tended to reinterpret the colossi through the lens of their own culture. They overlooked its pharaonic roots and instead saw Memnon, the mythical king of Aethiopia, serenaded by his anguished mother Eos, the goddess of dawn. It became a spectacle to behold and commemorate. Some 107 inscriptions have been catalogued at the bases of the statues: 61 in Greek, 45 in Latin, and one bilingual. They were not merely scratched onto the rock but engraved by professional stonecutters; the majority state some variation of ‘I have heard Memnon.’

Visitors were a diverse set, hailing from throughout the Roman Empire: Anatolian, Levantine and Corinthian Greeks, provincial administrators coming upstream from Alexandria, a Gallic soldier, and people from faraway Rome itself. Journeying to the southern extremity of the Empire for many of these visitors was no small feat.

An ancient traveller to Egypt or elsewhere had to consider the sheer investment of time, resources and effort. Yet throughout history, distant horizons and thirst for knowledge of the faraway has had relentless allure. Indeed, the notion that the Roman Empire consisted of isolated, immobile communities has been upended by modern scholarship. Recent examination of the empire’s vast territory, diverse peoples and long history reveals that travel offered adventure, novelty and opportunity for those with the resources or fortitude, making for a cosmopolitan ancient world.

Rome evolved from a small Latin settlement on the banks of the River Tiber in central Italy into a superpower, which at its most expansive in the 2nd century CE enveloped the entirety of the Mediterranean and stretched from northern England to the Middle East and, very briefly, the Persian Gulf.

Without modern mechanised transportation and confronted by enormous distances and varying weather by season, the ancient perception of distance had to have differed from our own. A long-distance journey in the Roman Empire, it has been posited, was anywhere beyond five days’ reach: quite the departure from our current ideal of anywhere not accessible within a few hours by car, plane or train.

A river scene fresco at the National Archaeological Museum, Naples. Photo by Getty

Those journeys were enabled by the unprecedented political reality of the empire, which emerged after the fall of the already-expanding Republic in 27 BCE under the first emperor, Augustus. Augustus’ imperial autocracy brought an end to the repeated civil wars and disastrous political instability of the late Republic. The two-century-long Pax Romana (Roman peace), and the stabilising influence of one-state rule, imparted a newfound sense of security.

For the ease of governance, economic growth and military activity, the empire was blanketed by a remarkably extensive network of infrastructure that united the far-flung corners of the realm with Rome and each other: paved roads, ports and harbours along coastlines, and navigable rivers supported a sophisticated maritime network.

Civilians could wander this bounty, a privilege that did not go unnoticed among commentators of the age. Writing to his grief-stricken mother in the 1st century CE during his exile, the philosopher Seneca the Younger mentioned a ‘certain restlessness that makes man seek to change his abode and find a new home’. The sentiment was later echoed by the 2nd-century sophist Favorinus of Arelate (Arles), who observed that ‘divinity has given an indefatigable nature’ to man, ‘who travels “on land and on waves”’. The impulse to travel was not purely driven by the utilitarian, but was intrinsic to the human condition.

There were no legal impediments to travel, nor any genuine borders in the modern sense

The 2nd-century Greek orator Aelius Aristides was especially evocative when marvelling at the empire’s territorial fluidity in his panegyric addressed to an unnamed emperor:

Cannot everyone go with complete freedom where he wishes? Are not all harbours everywhere in use? Are not the mountains as secure for the traveller as the cities for their inhabitants? … Is not fear gone from everywhere? For what river fords cannot be crossed? What straits are closed? … Now all mankind seems to have found true felicity.

Most notable here is the word freedom. The world as Aristides knew it was completely at his disposal, free of obstructions. There were no legal impediments to travel, nor any genuine borders in the modern sense, nor mass communications and technology that enabled their enforcement. Aristides and millions of his contemporaries enjoyed, at least theoretically, freedom of movement.

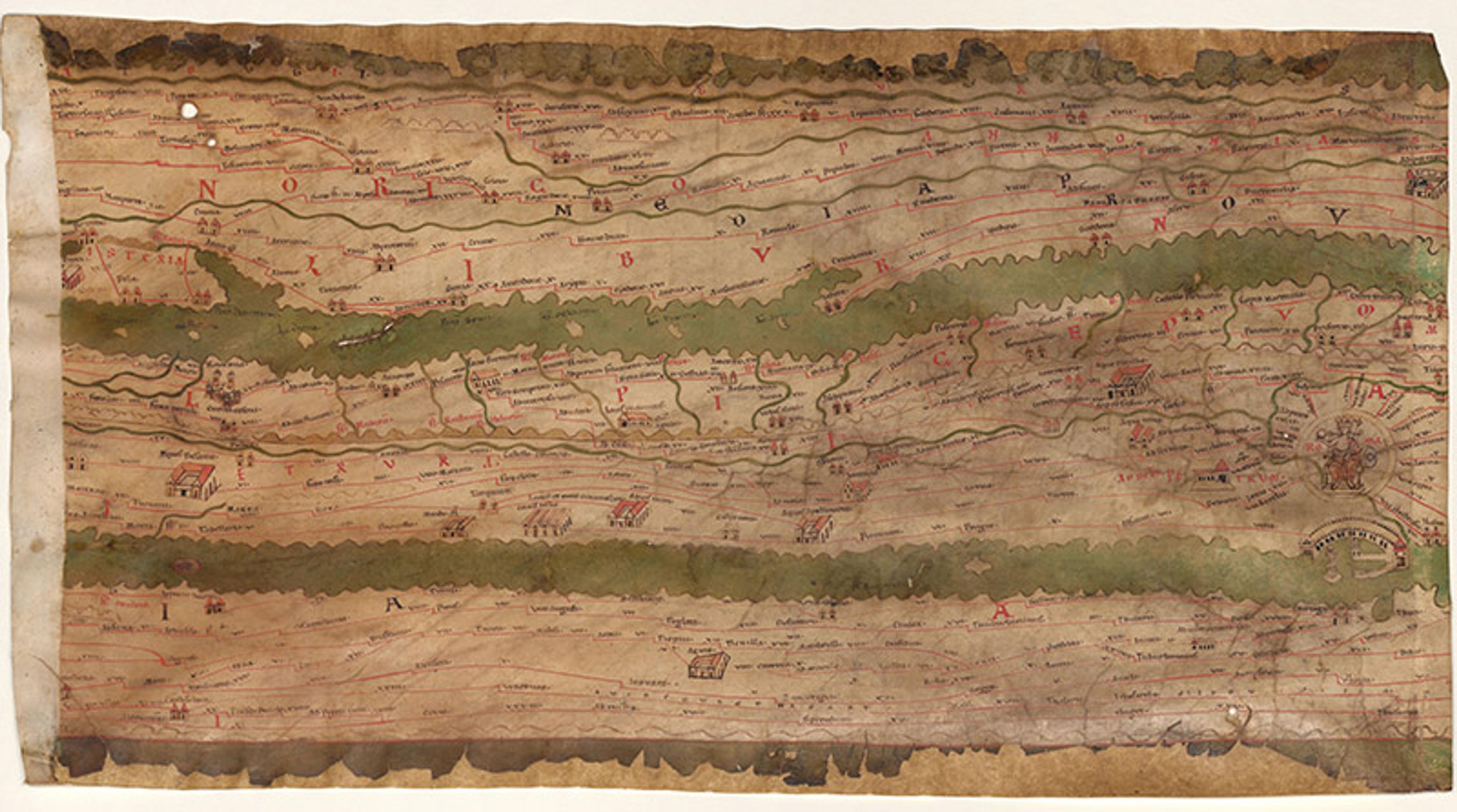

A section of the Tabula Peutingeriana (c12th century), the unique preserved map showing the roads of the cursus publicus, the public transport system in use during the Roman Empire. Rome itself is centre right in this section. Courtesy the Austrian National Library, Vienna

The Romans were largely resigned to the population flux that was a corollary of their own expansion, but there was some attempt at control. Augustus prohibited the entry of senators and knights of high rank into Egypt without his direct permission, lest they set their avaricious gaze on the riches to be found in empire’s breadbasket. Much later, in 370 CE, as preserved in the Codex Theodosianus, students who came to Rome required documents from their provincial judges granting them ‘the right to come to the City’; in the case of misconduct, a student would ‘be publicly flogged, immediately put on board a boat, expelled from the City and returned home’. Students could remain in the urbs until the age of 20, after which any overstayers would be deported.

Known restrictions like these were relatively few and far between, and specific rather than universalised. It was easier for the Romans to bring order and logic to their mobile society by simply keeping track. By the late Republic (c133-27 BCE), we see the emergence of legal terminology to categorise mobile individuals: peregrinus (non-citizen/foreigner), origo (one’s land of origin) and domicilium (one’s adopted homeland), to mention a few. By the 2nd century CE, the jurist Ulpius Marcellus legislated that ‘there is no barrier to anyone having his domicile wherever he wishes, provided somewhere is not forbidden to him’. Marcellus’ was a tacit acknowledgement that the empire rendered mobility an unavoidable, natural right. Control was the exception rather than the norm. Freedom of movement in the Roman Empire was as unhindered as it was guaranteed by law, if only because the state could not really control it.

But what propelled ancient Romans to venture forth beyond the confines of their native lands? While the average Roman lacked the time or resources for leisurely travel, for a more privileged elite minority, the impulse of wanderlust could be satisfied. Notably, the author and politician Pliny the Younger observed of his fellow Romans that:

We are always ready to make a journey and cross the sea in search of things we fail to notice in front of our eyes … Whatever the reason, there are a great many things in Rome and near by which we have never seen nor even heard of, though if they were to be found in Greece, Egypt or Asia, or any other country which advertises its wealth of marvels, we should have heard and read about them and seen them for ourselves.

Pliny’s perspective is a remarkably modern one. We take our homelands for granted, charmed instead by the exotic marvels of distant countries.

Exploration was already ingrained into Greco-Roman folklore. The Romans were well-acquainted with Homer’s Odysseus, who wandered the Mediterranean for a decade after the Trojan War before finally making it back to his native Ithaca. In his footsteps followed Aeneas, the protagonist of the Roman foundational epic the Aeneid, who meandered from Troy all the way to the destined site of Rome.

Eventually, an entire genre of geographic works and travel narratives catered to this curiosity. Geographies by Pausanias, Strabo and Pomponius Mela, and works such as Pliny the Elder’s encyclopaedic Natural History, all served to reveal foreign lands and peoples to the literate. Fiction was likewise a key medium: Encolpius, the protagonist of Petronius’ Satyricon, travels between Massalia (Marseille), Puteoli (in the Gulf of Naples) and Crotona (Calabria); Philostratus’ fantastical account of the Greek philosopher Apollonius of Tyana chronicles his alleged extensive travels throughout the Roman Empire and beyond into Nubia, Babylon and India.

Whereas disasters were once the force behind migration, personal agency came to assume greater influence

And so, equipped with knowledge and hearsay of distant wonders, the venturesome and able satisfied their curiositas by seeking them. Egypt, ingrained in literary tradition as a land of marvels, was an epicentre of this early tourism. The general Germanicus visited the country in 19 CE in order ‘to study its antiquities’. According to the historian Tacitus, he sailed up the Nile and became mesmerised with ‘the vast ruins of ancient Thebes’, the hieroglyphs and the country’s glorious pharaonic past, and above all the ‘wonders’ of the vocal Colossi of Memnon (those giant twin statues actually celebrating Pharaoh Amenhotep III), the pyramids, and southern Elephantine and Syene. A century later, Emperor Hadrian followed a similar itinerary on his own grand tour.

Other sightseers immortalised their presence via graffiti on monuments throughout the Nile Valley, from the Pyramids of Giza to the Colossi of Memnon and the tombs of the Valley of the Kings. We can partially trace the course of a certain touring Heliodorus of Caesarea Paneas, in the Golan Heights, who left an inscription on the base of the colossus stating that he had heard Memnon four times, after which he inscribed yet again on the temple of Isis at Philae to the south. We know it is the same Heliodorus because in both instances he makes reference to his two brothers, Zenon and Aianus.

Yet the gigantic, even surreal legacy of Egypt’s monumental heritage, remnants of an enigmatic golden age already millennia old, elicited criticism and condescension from the Romans as well. While the fame of the pyramids may have ‘filled the whole earth’, Pliny the Elder could not help but see them as ‘frivolous pieces of ostentation’ and expressions of ‘great vanity’.

Some Egyptians, nonetheless, were keen on receiving these awed visitors. Strabo claims that when he visited the city of Arsinoë, formerly – and aptly – named Crocodilopolis, he was taken by his guide to a lake where the sacred crocodile was kept. Tending priests would open the beast’s mouth and feed it ‘a small cake, dressed meat, and a small vessel containing a mixture of honey and milk.’ With the arrival, right after, of another visitor bearing offerings, the priests proceeded to chase the crocodile to repeat the process. Perhaps Strabo describes the first inklings of a tourist industry in which staged spectacles were part of the package.

It was the imperial mercantile economic order, however, that was not just shaped by but also propelled the growth of human mobility. Significant numbers of traders, businessmen, transporters and enslaved people were regularly on the move. Shipwrecks stranded on the Mediterranean seabed, laden with lost cargo, attest to the dynamism and extent of this economic exchange. Stamps on otherwise unremarkable domestic items illuminate just how far a company might operate: the terracotta lamps produced by the firm Fortis have been detected in their hundreds beyond their principal northern Italian workshop in Mutina (Modena) as far as Germany, Gaul, Pannonia, Dacia, Dalmatia and, to a lesser extent, central Italy, Spain and north Africa: undoubtedly the achievement of a decentralised business model with agents and branches appointed in distant markets. Meanwhile in Ostia, the main port of the consumer giant that was Rome itself, the mosaics that spread out over the surface of the Piazzale delle Corporazioni, exhibiting the stationes (commercial offices) of its merchants, betray the once-cosmopolitan atmosphere of this bustling meeting point, with references to traders from modern Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, Sardinia and southern France.

And with virtually no impediment to freedom of movement or domicile, the nature of migration underwent a fundamental transformation. Whereas once natural and manmade disasters were the historic force behind migration, personal agency came to assume increasingly greater influence. Whether temporary or permanent, there was a progressively voluntary aspect to migration.

It was free will, and a perception of opportunity and choice, that drove traders and shipbuilders to Ostia. It was aspiration that influenced students, in a most temporary form of migration, to depart for their education. The 2nd-century writer Apuleius, who left his native Madaurus in Numidia (modern Algeria) to study in Carthage and Athens, then travel through Egypt, Asia Minor and Rome, embodied the well-educated and well-travelled Roman. Cities attained expertise for particular academic fields: Alexandria remained an intellectual powerhouse in philosophy and the sciences. Athens too retained its historic expertise in philosophy and rhetoric. Beirut was famed for its law school.

Cities were naturally the main destination for migrants. Without a continuous stream of migrants, the larger cities of the premodern age, with mortality rates far exceeding birth rates, could not have grown or sustained their populations to the degree they did. By the dawn of the 1st century, Rome itself had reached 1 million inhabitants, an unprecedented demographic phenomenon at the time – and a significant proportion of this cohort comprised of enslaved people. The written record is laden with references to foreigners who continued to arrive, voluntarily or not. Epitaphs offer intimate insights into their identities, such as Basileus, the teacher from Nicaea in Bithynia (modern Turkey), or the Egyptian Fuscinus, who came to Rome with his wife Taon and became ‘the emperor’s provocator [gladiator]’ – they commemorated their deceased young son, who was given a Latin name, Serenus.

The capital was such a draw that the Greek poet Athenaeus of Naucratis referred to it as ‘the epitome of the inhabited world, since you can see every single city settled in it’. Seneca, himself a Spaniard, observed how crowds ‘from all parts of the world’ came to Rome for myriad reasons ranging from employment to vice, but would then leave and ‘travel from one city to another; everyone will have a large proportion of foreign population’. The poet Juvenal, in his Satires, records the alleged displeasure directed at Rome’s migrants by Umbricius, who is in turn emigrating southwards from Rome to Cumae – ‘Syrian Orontes has long since poured itself into the Tiber, bringing with it its lingo and its manners’ – but he cannot bear ‘a Rome of Greeks’. Satirical it may be, but it encapsulates what must have been a real school of thought among an element of the city’s denizens: xenophobia was not beyond the Romans.

It takes movement to bring exposure, and it takes exposure to instigate transformative change. With migrants, merchants, enslaved people, soldiers, tourists and pilgrims traversing the Mediterranean – visiting, settling, working and trading – like never before, the expansion of Rome set into motion an age of unparalleled intercultural communication and convergence. Never had the peoples of the Mediterranean world been so mobile, and thus so familiar with one another.

Yet the majority of the empire’s inhabitants were simple subsistence farmers, not long-distance voyagers; they were hardly inclined to travel or migrate unless necessity demanded it. But a ‘mobile society’ goes beyond sheer numbers. The ancient world, argues the historian Greg Woolf, was mobile in the sense that a minority of ‘movers’ (mostly, but not only, young, skilled males) travelled back and forth along well-traversed migration streams.

Because of them, the remaining majority of ‘stayers’, who rarely ventured beyond their small worlds, did not exist in isolation. The world belonged to the ever-more empowered movers, who showered the stayers with knowledge of the beyond: customs and aesthetics, ideas and information, materials and languages. Latin became the lingua franca of the Western empire, and increasingly a first language well beyond its native Latium, gradually evolving into today’s Romance languages. Meanwhile, in like manner, Greek persisted and flourished throughout the east. Multilingualism became a palpable facet of the empire’s multiculturalism. Roman religion, itself heavily influenced by the Greek, proliferated, and Eastern deities from the Egyptian and Greek pantheons and religions such as Mithraism, Judaism and – most momentously – Christianity were exported north and westward as far as Britain. It was the movers who seeded civilisation’s metamorphosis, permanently reshaping much of Europe and the Mediterranean.

People throughout the empire would consider themselves Romans without ever having been to Rome itself

The cities of the Roman Empire, as the principal nodes of communication and travel, came to serve as the junctions through which Roman standards of culture and lifestyle could infiltrate the provinces. Roman-ness became synonymous with civic life, and references abound to barbarian natives becoming civilised Romans upon their adoption of urban ways. The mundane repetitions of daily life allowed a ‘Roman’, whether in Rome or Britain, to form and consolidate their identity, and so to participate in a ‘shared cultural discourse’ that made the empire a cohesive whole.

Faced with an increasingly ambiguous and heterogeneous concept of Roman-ness, commentators looked to, and fabricated, the past to make sense of their present. In their view, their ancestral city-state, born seven centuries before the onset of the emperors, was never a homogeneous community with a distinct autochthony, but an amalgam of ethnicities: Italian Latins, Etruscans and Sabines, and eastern Arcadians, Achaeans, Pelasgians and Trojans. A spirit of inclusivity defined the city from the start.

It certainly made the new world of motley Romans more palatable. People throughout the empire would consider themselves Romans without ever having been to Rome itself. ‘Romans’ included millions of diverse people spread throughout the Mediterranean and beyond who, by the fruits of mobility, were living quintessentially Roman lives. Strong regional variations persisted, but were attenuated by an increasing commonality; mobile individuals and entire communities were assuming increasingly complex hybrid identities. The historian Claudia Moatti has called this coalescence ‘cosmopolitisation’: a process rather than a philosophy, in which people, marked by their own experiences with mobility, accumulated affiliations. Fundamentally, it resembles modern diasporas that spread traditions, languages and identities far and wide – from British Indians to Italian Americans, the dance goes on.

Identities could co-exist and complement each other, but Roman-ness itself provided the focal point of an admirable multiculturalism to millions of otherwise disparate peoples, a universal identity that anyone could aspire to attain. Aristides encapsulated this evolution succinctly, praising the city for having ‘caused the word “Roman” to be the label, not of membership in a city, but of a common nationality’.

This ‘common nationality’ was not merely a legal concept: most inhabitants of the empire were not actual Roman citizens until the Constitutio Antoniniana of 212 CE granted full citizenship to all free men. Until then, this plethora of Romans in all but city and citizenship, with all their distinctions, were bound together by what must have been a more practical and even emotional sense of kinship. Indeed, ‘Roma communis nostra patria est’, declared the Greek-speaking jurist Modestinus in the 3rd century CE: ‘Rome is our common fatherland.’

It’s hardly a leap to declare that, some two millennia ago, in the Roman Empire, an early version of ‘globalisation’ first reared its head. It was this interconnectivity and the Roman tolerance of plurality that glued the empire together and made it ultimately work and flourish for centuries.

Make no mistake: liberal ideals were not the impetus behind the ‘cosmopolitisation’ of the Roman Empire. There was no progressive democracy, but an imperialist machine that expanded and thrived through violent conquest, subjugation, exploitation and slavery. Nor was ‘Romanisation’ an absolute or uniform process throughout the empire: it was felt less acutely in relatively remote, little-urbanised regions. Xenophobia and nativism contradicted the supposed inclusivity of imperial Roman-ness, which was in itself bound up with notions of the perceived superiority of Roman civilisation. Rome could both embrace and disdain the foreign. Just as Egypt’s wonders were marvellous and frivolous, so was the diversity of Rome’s migrants a source of pride and dread. Xenophilic or xenophobic, there is no use in generalising the attitudes of the time: the inconsistency is a reflection of how Romans across the empire were processing their increasingly cosmopolitan reality.

The cultural transformations brought by Rome permanently altered the course of European history and society. The extent of this legacy demands we question the idea that Romanisation was solely the homogenisation of powerless, victimised native peoples into a pre-existing social order. Instead, in multifarious ways, these peoples participated in the creation of a new world. For better or worse, that world was ripe for exploration, familiarisation, interaction and, ultimately, self-introspection: travel was opening and deeply transforming minds.