Mosul’s old city lies in ruins. A major section of the third largest city in Iraq has been destroyed by war. Two years after the Iraqi government and the United States-led coalition recaptured it from ISIS, the city is still noticeably scarred. Many residents have fled, or are detained in camps elsewhere in the country. Those who have returned live amid the ruins of their old houses and their old lives. But what is being reconstructed is cultural heritage. UNESCO has worked with the Iraqi government to launch a campaign called ‘Revive the Spirit of Mosul’, focusing on a handful of historic monuments in the city. The United Arab Emirates has pledged $50 million to rebuild the 850-year-old al-Nuri mosque and its minaret, known as al-Hadba (or the hunchback), a symbol of the city.

What is most striking about this campaign is its seeming indifference to the lives of the people who call the city home. UNESCO’s promotional video pans through the old city; block after block after block lies completely devastated … only for the camera to abandon them for the one monument that will actually be rebuilt. What kind of reconstruction is this, and who benefits from it? Certainly not the residents. Many Iraqis suspect that the Shiite-led national government is exacting revenge on the Sunni-majority population of the city. Instead, it appears that the main beneficiaries are the governments gaining prestige by launching and funding this campaign.

Cases such as Mosul’s highlight a key fact about cultural heritage: it is not primarily about the past – as counterintuitive as that might be. It is about the present. Heritage harnesses the power of the past to justify present social relations, especially relations of power. Governments trample over the lives and needs of individuals and communities, the wealthy convert their dubiously acquired wealth into cultural capital, all in the name of that heritage. And in our conviction that we must protect the remains of the past, the rest of us are often swept up in the enthusiasm. We don’t even question the relatively new idea of cultural heritage – that the remains of history are to be unquestionably treasured as our inheritance from the past and must be preserved in their original state. Or that what typically counts as cultural heritage are major historic buildings and monuments, perfectly suited to be exploited as symbols of the powerful.

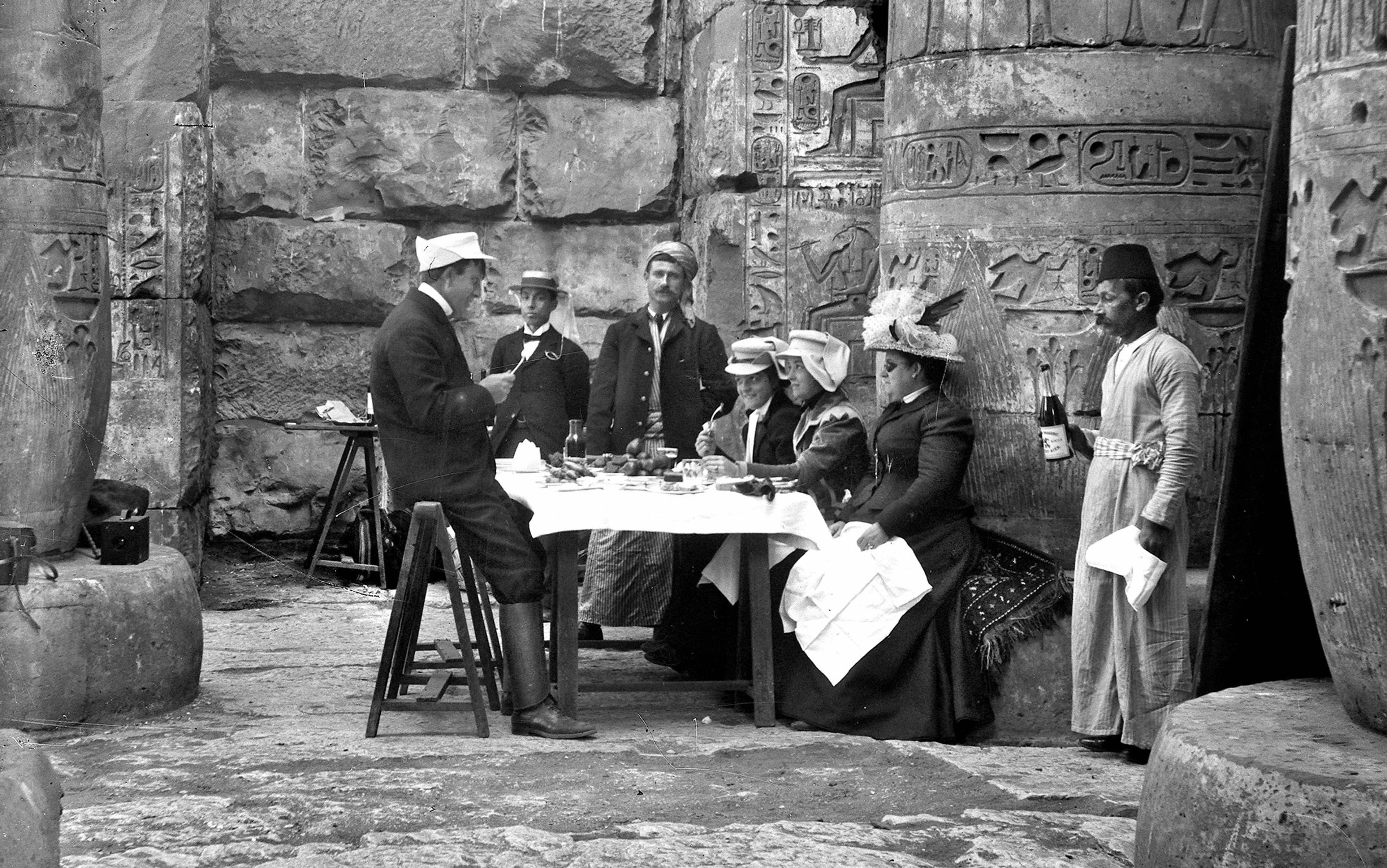

We have always been interested in the remains of the past. But our current way of thinking about heritage began to take shape in the 19th century. Europeans looked to preserve medieval buildings at home. And in the Middle East, interest in cultural heritage grew as monuments of the ancient past were threatened by modernisation and theft. Egypt in 1835 and the Ottoman Empire in 1869 instituted laws to protect monuments and artifacts from theft and destruction. But these laws were widely disregarded by Europeans and Americans. ‘Mehemet Ali, not satisfied with those [monopolies] he has established on the living, has lately introduced one also in the kingdom of the dead,’ was how the correspondent of the London Morning Post in Constantinople dismissed the law in 1835. Everyone from antiquities dealers to the Baedekers travel guides gave advice on how to illegally purchase looted antiquities in the Middle East, or to conduct your own illegal excavations, or to remove antiquities by bribing customs officials and police officers. E A Wallis Budge, the head of Egyptian antiquities at the British Museum, spoke openly of the elaborate ruses he had used to smuggled ancient papyri out of Egypt.

Such was the situation in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. While the years between the two world wars ostensibly saw more international collaboration via the League of Nations, heritage did not necessarily follow suit. When now-independent Iraq was drafting a new antiquities law in the 1930s, British archaeologists were outraged that the share of finds they could take from the country was reduced. (Even the British Foreign Office dismissed their attitude as ‘irritating and condescending’.)

The situation truly changed only in the aftermath of the Second World War. The British and other imperial powers began to shed their colonies in earnest, and international agreements such as the 1954 Hague Convention, and the 1970 and 1972 UNESCO conventions codified respect for these new nations and their heritage. These agreements are rooted in the concepts of national sovereignty. They have enshrined the principle that cultural heritage belongs to the nation in whose territory it is found, and call for recognition and enforcement of national laws of cultural property. These conventions represent the final step in the transformation of attitudes toward antiquities laws of developing countries from dismissal to respect. But they have also enshrined and encouraged the use of cultural property for nationalist purposes.

Governments increasingly looked to remains of the distant past to bolster national identities and a sense of greatness, or to marginalise disfavoured groups. Saddam Hussein used the ruins of Babylon to spread ideas of Iraq’s greatness as well as his own, even portraying himself as a modern Nebuchadnezzar. China’s leadership has used archaeology to project national greatness onto the distant, semi-legendary past. Today, India’s prime minister Narendra Modi’s Hindu nationalist government has worked to use archaeology to prove that modern Hindus can trace their descent from the earliest inhabitants of India.

With this sanctioned nationalist use of heritage has come hostile, even violent reaction. Looting and vandalism of cultural heritage are sometimes seen as a form of resistance to nationalism. In its most extreme form, this resistance has resulted in widespread campaigns of destruction. The Near-Eastern historian Christopher Jones has argued persuasively that a major motivation for ISIS’s destruction of monuments in Syria and Iraq is the role of those monuments as symbols of ‘idolatrous’ secular nationalism.

European countries hesitated to be subject to the same interventions that they proposed for the rest of the world

Alongside the language of nationalism, international organisations also associate cultural heritage with universal values. They argue that cultural heritage belongs not just to individual nations but to all of humanity. UNESCO, for example, promotes ‘Unite for Heritage’, a popular social-media hashtag campaign. The UNESCO World Heritage List presumes the universal value of heritage. At first blush, the universalist trend seems to be a new one that directly challenges older nationalist ideas. But, in fact, it is neither new nor a challenge. In the 19th century, Europeans often spoke about Egyptian antiquities, as Elliott Colla points out in Conflicted Antiquities (2007), not in terms of the political or commercial interests of their nations – as they did with other aspects of Egypt – but of civilisation in general. When in the 1820s Jean-François Champollion, the French decipherer of hieroglyphics, was questioned about his plan to hack painted reliefs from an ancient Egyptian royal tomb, he replied that he was doing so as a ‘real lover of antiquity’. That Champollion worked for the Louvre, his country’s national museum, and the reliefs would be deposited there, was mere convenience. The French elite saw themselves on a civilising mission to ‘barbaric’ Africa, an altruistic enterprise benefiting humanity that just happened to include ancient Egyptian monuments and artifacts as their country’s reward. ‘If Africa becomes humanised, if civilisation ever flourishes again on its shores, where the monuments of Roman grandeur lie,’ according to one writer in 1836, ‘the glory must come back to France.’

In the 20th century, the League of Nations and its successor, the United Nations, both initiated heritage campaigns that centred on the claim that cultural heritage belongs not to individual nations but to all. The high-water mark of this universalism is UNESCO’s Nubian Monuments Campaign of 1960-80, when several nations came together to rescue Egyptian monuments from the lake formed by the construction of the Aswan High Dam. But while these were couched in the language of global cooperation, in practice they were a one-way flow of expertise and standards-setting, from Western powers to developing countries. European countries hesitated to be subject to the same interventions that they proposed for the rest of the world.

National museums in Europe invoke universalism to justify holding on to the cultural heritage of other countries (like the British Museum with the Parthenon sculptures). Western scholars call on UNESCO to protect precious manuscripts from the religious groups that own them – and who restrict Western access to them. Invoking universalism often functions in a very non-universal way: not to promote sharing and cooperation among all, but so that one side wins out over another in a battle of particular – often national – interests. My claim trumps your claim.

Universalist language serves a double purpose. It justifies the urges of the developed world to acquire, often in effect to loot, heritage from developing nations. And it does so while presenting those same developing nations as less enlightened. But this characterisation of developing nations runs counter to the actual history. In 1989, John Henry Merryman, professor emeritus of law and art at Stanford University, questioned ‘[t]he deference still routinely given to state claims to their “national cultural patrimony” in international affairs’. At the time, European and American powers had just begun taking the antiquities laws of developing nations seriously. Western scholars love to critique and mock the image of Hussein as Nebuchadnezzar, but it is not qualitatively different from Napoleon’s depiction as a Greek god or hero, defeating the Mamluk rulers of Egypt and bringing civilisation back to the country. In Europe and America, nationalist use of heritage is depicted as an aberration. It’s what others do. The West rarely holds itself up to the same mirror.

Nations don’t use heritage just against other nations, but against their own populations as well. Communities, especially marginalised ones, that continue to live at historic sites are especially endangered. In the late 19th century, Greece held a contest in the US and Europe to see who would get to excavate at the site of ancient Delphi. Contestants had to put up the funds to remove the modern village of Kastri in central Greece from the site. The French won. In French Mandate Syria, too, the French forcibly relocated the villages at Palmyra and inside the Crusader castle Krak des Chevaliers so that they could excavate further and preserve the ruins.

The removal of communities in the name of heritage continues today, only now with the imprimatur of UNESCO. While much of the world came together to save ancient remains in the Nubian campaign, the modern Nubian inhabitants were not so fortunate. Roughly 100,000 people were forcibly relocated, and their resettlement underfunded. Inscription of a site on the World Heritage List brings increased prestige and tourist dollars. With these comes increased pressure to remove longstanding communities. From Petra in Jordan, to Wuzhen and the old town of Lijiang in China, to Casco Viejo in Panama City and many more cases, World Heritage listing has brought evictions. In Chikan in China, thousands of residents are being forced out of their homes by a $900 million development plan to turn the old town into hotels and boutique shops for tourists visiting the nearby World Heritage site of Kaiping. But the houses of Chikan are themselves historic.

For decades, the Egyptian government tried to remove the village of Gourna, built on part of ancient Thebes. Thebes was designated a World Heritage site in 1979, a development that has helped the Egyptian government in evicting villagers from their homes. UNESCO and other international organisations have tended to ignore these forced dislocations, at best offering muted and belated criticism. Besides its attention to ancient Thebes, the only project that UNESCO lists about the site online is the project to protect New Gourna Village – a ghost town built in the 1940s and ’50s to house villagers in an earlier eviction attempt.

In the Syrian Civil War, every party in the conflict has used heritage as a weapon

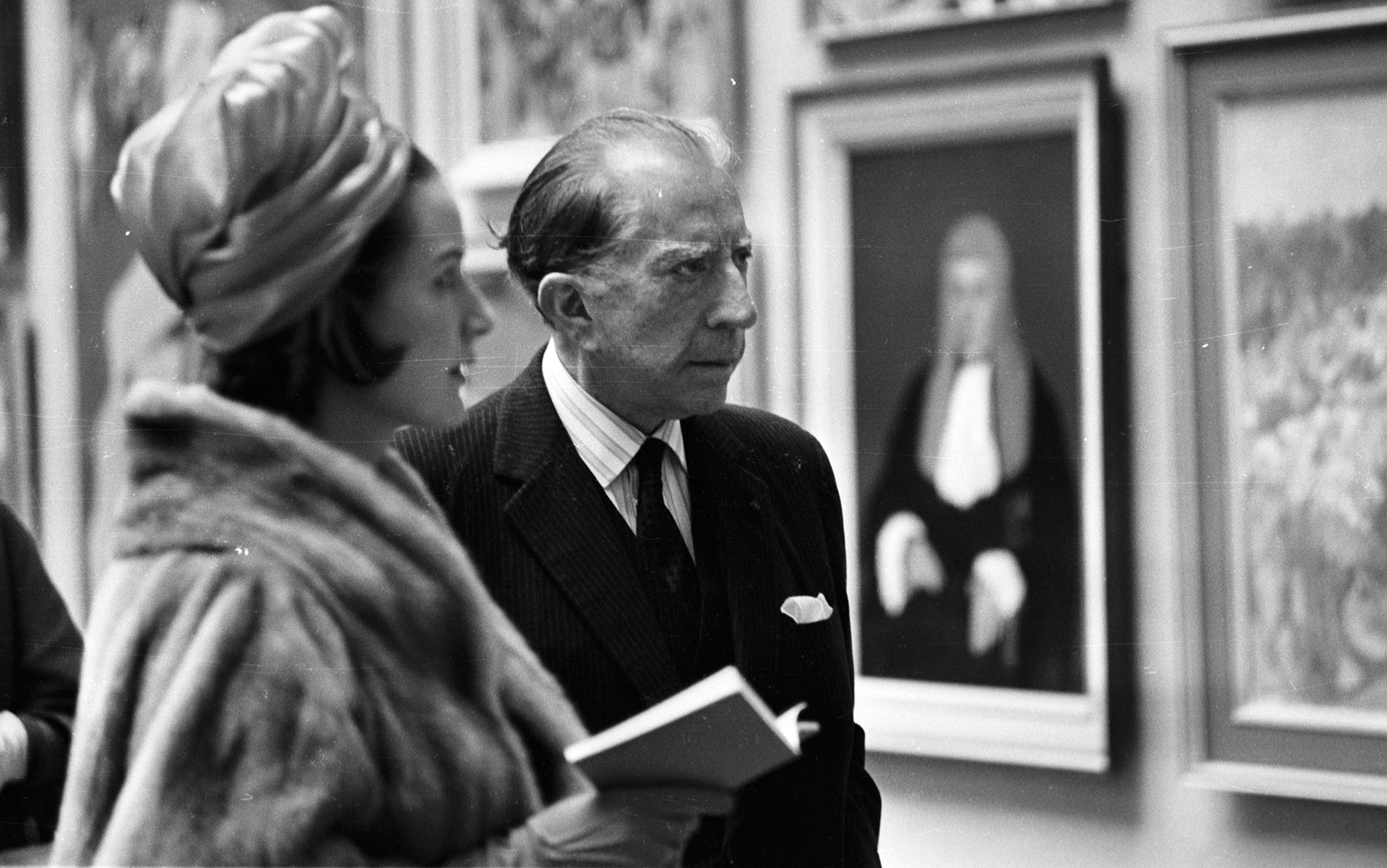

The seduction of heritage money is strong. It can even transcend national interests, representing the flow of both economic and cultural capital from the elite of one country to another. France entered into a multibillion dollar agreement with United Arab Emirates to create the Louvre Abu Dhabi and loan paintings to UAE. Not to be outdone, the Saudi crown prince Mohammed bin Salman followed with a multibillion dollar Saudi-French partnership. It makes for good cultural public relations. Who benefits from the idea of cultural heritage here? Museums and other heritage institutions have a symbiotic relationship with their wealthy donors: donors get good publicity and a tax break, while institutions get to be custodians of art and heritage and to profit off them. After the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York began charging out-of-state residents admission in 2018, the museum’s director criticised average museum visitors for not subsidising the museum enough, while praising the wealthy donors who give it money and paintings and sit on its boards. That museums are places for the rich is clear: they both house and create great wealth.

Deadliest of all, cultural heritage can be a weapon in war. Here, all the different political and economic strands of heritage come together. In the Syrian Civil War, every party in the conflict has used heritage as a weapon. ISIS has demolished monuments as spectacle and released sensationalist videos to frighten. Russia put on a classical music concert to celebrate its capture of Palmyra from ISIS. In 2014, when the Met inaugurated its ‘Assyria to Iberia’ exhibition, the then US Secretary of State John Kerry spoke at the opening ceremony, in effect using it as a launch event for a US military attack. Kerry’s speech focused on the destruction wrought by ISIS, which he exaggerated while ignoring acts of destruction by other parties in the Syrian Civil War. Kerry issued a call to stop ISIS, and just hours later, the US started to bomb Syria.

A year later, ISIS took control of Palmyra. The British politician Boris Johnson repeatedly condemned ISIS as ‘barbarians’ for their destruction of its cultural heritage. Journalists and scholars wrote articles and gave interviews telling us of Palmyra’s great legacy in the West. A crop of digitisation and restoration projects for ancient Palmyra sprang up at universities and other institutions, as well as a set of exhibitions at museums memorialising ancient Palmyra amid the destruction. Think of the readers of these articles and the visitors to these exhibitions. Most had probably never given Palmyra much thought. They were now being told how important it is for the modern West. However well-intended, the cultural heritage campaign served to help the continued bombing of Syria and ongoing supply of arms to warring parties. Syrians themselves are rarely asked what heritage they want to preserve. When they are, the ruins of Palmyra are rarely mentioned. Instead, Syrians focus on the buildings that are central parts of their own communities.

Whether we look at political, economic or military capital, one thing is clear. Heritage is a top-down idea – it is defined and used by the most powerful members of society, rather than by society as a whole. Cultural heritage tells people – it does not ask them – what they should care about. How can we change this?

Cultural heritage experts have proposed ideas that have the potential to help democratise cultural heritage:

1. Give greater control to local communities.

Key problems with the exploitation of heritage result from control on the national level. What if more decisions about heritage were made on the local level instead? Local authorities might be more responsive to the everyday needs of people who live at cultural heritage sites than to the symbolic needs of tourists or the state. Making cultural heritage more local might also involve recognising things that matter to working people, as opposed to just monumental structures and artifacts that tend to relate to royalty or the elite. Scholars have thought about how to make cultural-heritage ownership more communal (instead of private or state). One model might be the treatment of historic buildings in the US. The federal government may provide assistance or funding for preservation through the National Historic Landmarks Program and the National Register of Historic Places. But it does not manage or control the buildings. Instead, that rests with individual cities and towns, which can decide whether to tear down a building, move it, preserve it as a museum, or allow it to continue as a residential or commercial property.

2. Reduce the importance of the original.

Original versions of things are highly prized in Western society. They fuel everything from the possessive obsessions of antiquities collectors to the flood of money from heritage tourism. They must be protected at all cost from destruction. But what if we didn’t care about collecting and preserving originals quite so much? East Asian societies do not have the same concept of originals. Instead of completed works of art, Chinese thought imagines art as continually updated; it also finds great value in replicas. Other non-Western streams of thought also have strikingly different attitudes toward the broken past, from the Japanese practice of kintsugi (a method of repair that emphasises breaks instead of trying to hide them) to the Middle Eastern understanding of ruins as a step in the evolution of living buildings and cities rather than something that must be preserved in its original state to commemorate the past, or their historic reuse of ancient architectural fragments in new buildings for their protective power.

‘Not everything can be saved or perhaps should be’

We are at a moment when replicas and recreations can play a larger role in thinking about heritage. Digital reproductions are ever more present. They can offer the same visual and even tactile qualities as originals. Many museums and heritage sites already incorporate them into displays. Appreciation of reproductions can help lessen struggles over original artifacts and monuments.

3. Rethink the idea of heritage as property.

John Carman, senior lecturer in heritage valuation at the University of Birmingham in the UK, has proposed thinking of cultural heritage as an open-access resource. Doing so would make it available to all who are interested. Those who value a monument or object would be free to use it for their own purposes, without excluding others. Carman argues that this way of thinking about heritage, while it seems quite radical, does indeed have precedent in our political thinking. Certainly, changing the concept of cultural property has promise for dealing with the many cases where multiple parties struggle to own or exploit cultural heritage.

Each of these ideas has problems. Communities are not monoliths. Weighing different interests can be challenging, in particular those of local communities vs diaspora communities. And in some cases, it is the local government leading the charge for eviction in the name of heritage. Meanwhile, the effect of multiple copies – both through earlier mechanical reproduction and today’s digital reproduction – paradoxically seems to increase the value of originals. And how would open-access heritage work in practice? In particular, what would we do with cases where some see a heritage item as what the archaeologist Lynn Meskell calls ‘negative heritage’ – a site associated with negative memories or symbolism that might need to be destroyed – while others see it as a positive? Examples abound, from Confederate statues to Joseph’s Tomb. ‘Not everything can be saved or perhaps should be,’ Meskell rightly says. But who gets to decide?

If the flaws of cultural heritage are not addressed, it will remain a tool of power, and a deadly one at that.