In 1928, the UK physicist Paul Dirac stumbled on an equation that seemed to show that, for every particle, there’s another, nearly identical particle with an opposite electric charge. Just four years later, the US physicist Carl David Anderson proved Dirac’s prediction correct by capturing a picture of a ‘positron’ – a particle with the same size and mass as an electron, but with a positive charge rather than a negative one. This rapid series of developments unlocked one of the most momentous and enduring conundrums of physics: if particles with opposite electric charges annihilate one another when they meet, why is there any matter left? And if there’s no more matter than antimatter in existence, then the Universe should have annihilated itself soon after the Big Bang – yet, here we are. This brief animation breaks down this extraordinary, nearly century-long science puzzle, detailing some of the surprising explanations posited by contemporary physicists.

Logic tells us that antimatter should have annihilated the Universe. So why hasn’t it?

Animator: Eoin Duffy

Writers: Justin Weinstein, Brian Greene

Websites: World Science Festival, Studio Belly

27 June 2019

videoQuantum theory

Why aren’t our everyday lives as ‘spooky’ as the quantum world?

7 minutes

videoPhysics

Groundbreaking visualisations show how the world of the nucleus gives rise to our own

10 minutes

videoPhysics

If life feels out of balance, don’t worry – there’s always symmetry below the surface

4 minutes

videoPhysics

What does it look like to hunt for dark matter? Scenes from one frontier in the search

7 minutes

videoPhysics

How two scientists built a bridge between Newton and Einstein in ‘empty’ spaces

5 minutes

videoPhysics

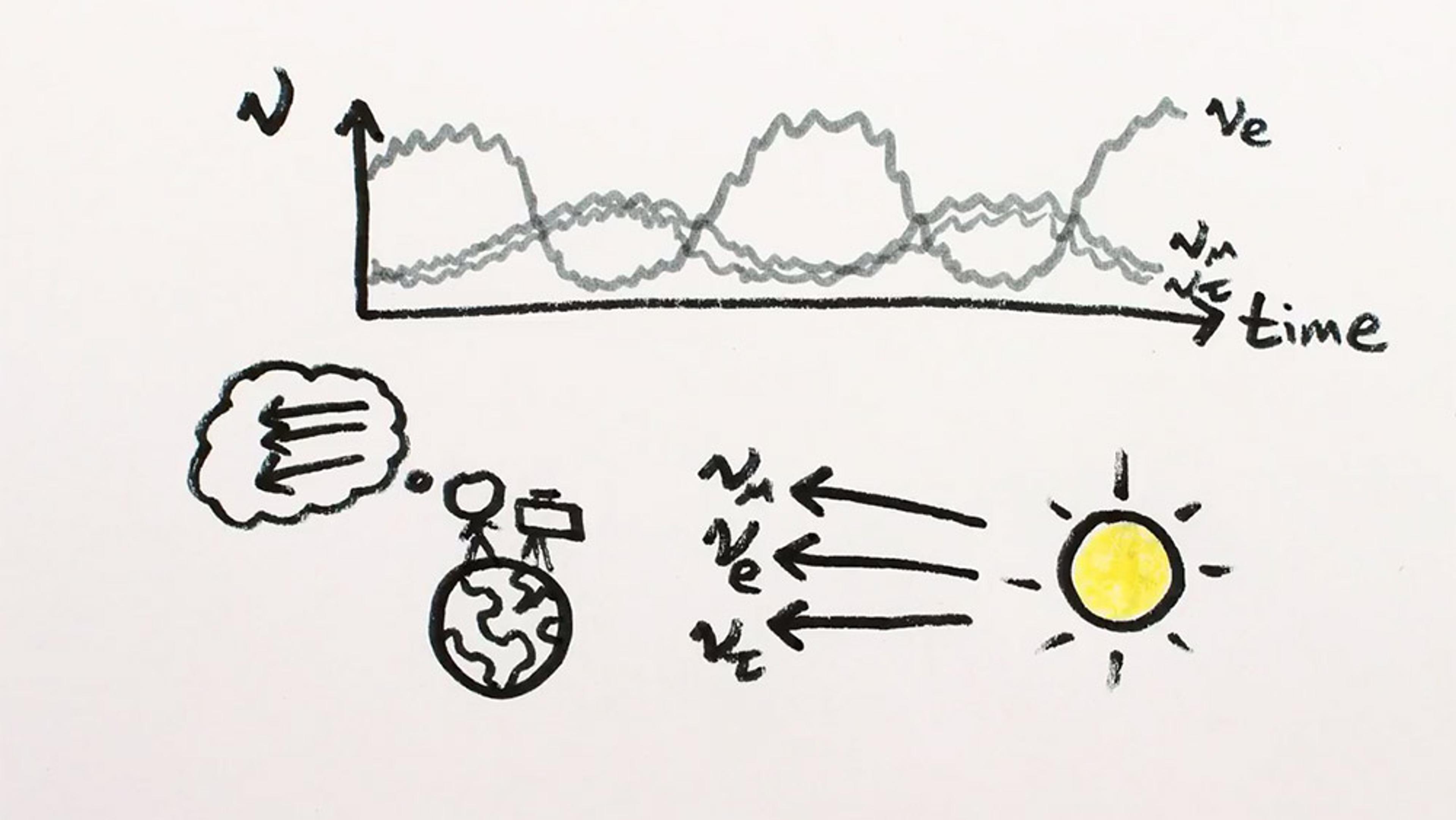

How the ‘identity agnostic’ neutrino exists in three states all at once

3 minutes